|

|

In this special report, EdNC looks at how the pandemic impacted education and what that means for the future. Read the rest of the series here.

The past year has been one of enormous stress and loss for many young children, families, teachers, and leaders. It has also been one of hope.

And it has looked different for different children, reflecting the wide variety of early childhood environments across North Carolina’s early learning continuum and across communities.

In some early learning environments — child care centers and home-based facilities — teachers and students learned new protocols, kept their doors open with little viral spread, found new ways to engage with families, and filled in gaps in care for older remote learners.

Early in the pandemic, North Carolina was one of the first states to provide bonus payments to child care teachers, who were deemed “essential” during stay-at-home orders and served children of essential workers facing health and financial uncertainty.

Low pay and disparities in pay across settings pointed toward longstanding issues involving the financing of early care and education. Strengthening the early childhood workforce through compensation and education, experts say, is a key place to start when furthering investment in early learning as a public good.

Share your thoughts with us by tweeting with the hashtag #PandemicSchoolYearNC.

In other early learning environments — some pre-K programs and elementary schools — teachers and students pivoted to online instruction and learning. Then, they created in-person and remote options for families, weighing complicated decisions and finding ways to meet families’ needs from food to mental health to academics.

Both pre-K and kindergarten classrooms saw sharp enrollment declines. As students return to classrooms from various settings, educators and policymakers are asking how to accelerate learning while addressing the social and emotional well-being of children, especially those who experienced loss or trauma.

As the state eyes new strategies to increase reading proficiency and expand pre-K access, early childhood advocates are hoping for smart investments in the entire continuum of early learning.

For this piece, as well as for all of EdNC’s early childhood coverage, “early learning” encompasses learning environments in children’s first eight years of life — including private child care centers and home-based facilities, pre-K classrooms in private and public settings, and K-3 classrooms.

EdNC spoke with national, statewide, and local early childhood leaders and asked how they hope the state’s pandemic experience shapes early learning in the years ahead.

Supporting a workforce that showed up

Early educators saw recognition of their work during the pandemic — from an “essential” designation and bonus payments for child care teachers in the early months to gratitude from parents who returned their children to classrooms after struggling at home.

Yet for many early educators, especially those working with the youngest children, that recognition came during a difficult experience on multiple fronts.

“We’ve seen [early educators] talked about as first responders, for example … and that’s absolutely true, but the truth of the matter is that they were asked to work through this very dangerous time with abysmal compensation, without health care benefits, by and large, and without something as simple as a paid sick day during a pandemic.”

Dan Wuori, senior director of early learning at The Hunt Institute

Teachers were leaving the field for better-paying jobs before the pandemic. A 2019 survey from Child Care Services Association (CCSA) found low pay was the top reason that about 2,300 early childhood educators left their teaching positions, and the majority left for a job outside of education. CCSA’s 2019 workforce study found that, in the prior 12 months, 21% of the full-time teaching staff had left their early care and education program and 19% were planning to leave in the next three years.

Early learning programs now face additional stress and turnover.

“The workforce crisis is huge,” said Michele Rivest, senior campaign director at the NC Early Education Coalition. “We are not seeing programs able to recruit and fill existing positions. Will the workforce return? It’s a major question.”

Those in the field are hoping early educators’ role in the pandemic will lead to workforce supports and pipeline investments across settings in the short and long term.

“One of the things we have to remember is the early educator workforce never went away during COVID; they never stayed home,” said Tara Willeford, family support specialist at Carteret Partnership for Children. “Some type of continued reward or compensation for that dedication would be great.”

In Carteret County, Willeford said, lack of access to a four-year college presents additional problems when thinking about creating a sustainable pipeline of early childhood teachers for children starting at infancy. So does competition from the public school district.

“A lot of times what happens is if they receive a four-year degree, they’ll go into the school system, with NC Pre-K, which is wonderful, but I think that we lose out on the opportunity to have those high-quality educated teachers in our child care classrooms,” she said.

Private providers losing teachers to pre-K or K-12 classrooms is a trend, to different degrees, across the state and country. Some local communities have established pay parity between NC Pre-K teachers in public and private programs to help solve this issue.

Caitlin McLean, researcher at the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, said more public investment in pre-K has had unintended consequences on the early childhood workforce and program access, especially when it comes to the youngest children.

“It’s great that there’s been this attention paid to pre-K services, but we really need to expand that across the 0-5 age range, or else we’re just perpetuating disparities for children in that age and for the workforce that’s caring for and educating them,” McLean said after the report’s release in February.

‘The centerpiece of everything we do’

Strengthening the early childhood workforce across settings is at the heart of strengthening the state’s system of early learning, researchers and advocates say.

“Attracting, recruiting, retaining a qualified workforce — it’s got to be the centerpiece of everything we do, because really they hold the key to whether there are benefits for children and families,” Rivest said. “That is a huge challenge ahead of us. And we know that it all begins with compensation.”

Early educator pay and working conditions are different across early childhood settings.

In 2019, North Carolina early educators were seven times more likely to live in poverty than K-8 teachers, according to the 2020 Early Childhood Workforce Index from the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. The median wage was $10.62 for child care workers (compared with $11.65 nationally), $12.83 for preschool teachers ($14.67 nationally), and $27.89 for kindergarten teachers ($32.80 nationally).

“This disparity is especially harmful to Black women working in centers, as they are more likely than their peers to work with infants and toddlers, and to Black, Latina, and immigrant women working in home-based settings, where a large share of infants and toddlers are in care,” the report’s overview reads.

2020 Early Childhood Workforce Index

The index also found teachers of color face pay disparities. Black early educators were paid on average $0.78 less an hour than their white peers at the national level.

“We need to create a unified workforce system that recognizes that early education teachers can work in whatever settings, and can teach whatever age group, but at the minimum, we should expect a level of a wage and benefit that is commensurate with how we believe that early childhood education matters,” said Iheoma Iruka, research professor of public policy and the founding director of the Equity Research Action Coalition at Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill. “If you believe that the first 1,000 days is so important, but then you pay a teacher basically $10 an hour, that tells me you don’t believe that.”

Experts point to wage supplements, like those offered through CCSA, as opportunities for states to increase both compensation and the education levels of early educators.

Wuori said some states like Illinois are considering creating early educator bachelor’s programs at community colleges to increase postsecondary access. Biden’s pre-K proposal includes teacher scholarships and free community college with the aim of supporting early educators.

The remedial plan in the long-running education lawsuit called Leandro suggests matching early childhood teachers’ salaries with educational attainment, ensuring that teachers have access to health insurance, and creating an early educator preparation program similar to NC Teaching Fellows. That program covers students’ tuition in exchange for a teaching commitment in certain subject matters.

Under President Biden’s American Families Plan (which must first pass a narrowly divided Congress), child care and pre-K teachers would earn at least $15 an hour and “those with comparable qualifications will receive compensation commensurate with that of kindergarten teachers,” according to a White House statement.

Gov. Roy Cooper’s budget proposal would allocate $9 million in recurring funds to “narrow the compensation gap between B-K licensed educators in private child care and their K-12 counterparts.”

With American Rescue Plan relief funds on the way, Wuori said, states are struggling to use one-time money to address compensation issues.

“Obviously the compensation of the early childhood workforce is a huge issue, but it’s one that I think states are looking at very cautiously with this money because of the question of … when you increase somebody’s salary … there’s this expectation that it’d be sustained.”

Rivest said long-term investments, like creating salary schedules similar to K-12 teachers in the state base budget, are critical.

“We need to make sure that child care becomes a regular part of the infrastructure of our state, because that’s what the pandemic has pointed out: child care is essential. Families can’t go to work, children don’t get early learning experiences that are going to pay dividends down the road because they’ll be ready for school and they’ll be successful at school.”

Michele Rivest, senior campaign director at the NC Early Education Coalition

Rethinking care, education, and the dichotomy between the two

The pandemic has highlighted differences in workforce and child supports in “care” and “education” environments, Rivest said. As public school districts went remote, parents who needed to work in-person searched for options.

“When schools shut down, parents had a child care dilemma,” Rivest said. “For working families, your 6-to 12-year-olds going to public school solves a big part of your child care dilemma between 8 and 5. And so parents lost that, and they immediately went to their local child care program or community center who were suddenly asked to be doing school-age programming, and providing space for tutoring, and supporting remote learning.”

This dynamic, Rivest said, is an overall positive for the early learning continuum.

“It elevated the importance of the role child care programs play,” she said. “They were serving as off-site education centers for the public schools. Nobody talks about them that way, but that’s what they were, and that’s what they did.”

Rivest said she hopes for a future where “there is this recognition and understanding that child care is education, education is child care in the early years.”

‘Bedrock of the economy’

Inadequate child care before the pandemic was costing the state $2.4 billion annually, according to a December report from the NC Early Childhood Foundation (NCECF). During the pandemic, that number grew to $2.9 billion, factoring in losses from families, businesses, and state government.

The report also looked at how the pandemic affected parents’ child care arrangements and work life. In a survey of 802 working families across North Carolina, 47% said they missed a full work day due to inadequate child care, and 37% said they had problems finding a job due to child care issues.

Across the country, women left the workforce at greater rates than men, often citing child care challenges. This phenomenon led to many referring to the pandemic’s recession as a “she-cession.”

“I think there is a better understanding that child care is really, in a lot of ways, the bedrock of the economy, in the sense that it is the industry that enables all other industries to work. It’s coming into really sharp relief how valuable the system is and at the same time how inequitable the system is.”

Dan Wuori, senior director of early learning at The Hunt Institute

Experts point to subsidy assistance, which helps low-income working parents afford child care, as an example of that inequity. Recent estimates put the subsidy waitlist in North Carolina at 13,000 children. In 2019, that number was around 38,400 children.

Biden’s spending plan would include a sliding scale of child care assistance, with the lowest-income working parents paying nothing and working families at 1.5 times their state median income paying no more than 7% of their incomes.

For much of the last year, North Carolina has covered parents’ subsidy co-payments, based reimbursement on enrollment instead of attendance, and increased the income threshold for receiving help to essential workers. Some of those supports might be good ideas to continue, said Michelle Hughes, executive director of NC Child.

“[A] lesson learned from the pandemic is that we can make policy choices as a state, as a country that make a difference, and that some of the things that we temporarily put in place, we should make permanent because they actually strengthen and build the child care system and make it something that really can become affordable and accessible to all children.”

Michelle Hughes, executive director of NC Child

The rates providers receive in North Carolina to serve children through subsidy assistance vary widely by location. North Carolina advocates have been pushing not only for expanding subsidy assistance, but for rethinking how the rates are calculated and how the funds are distributed across the state.

Advocates have proposed establishing a floor subsidy rate, which would mean paying child care providers at least the state average regardless of location. Increasing the rates to the most recent federal standard (from a market rate survey in 2018) and establishing that floor are components of a bill (House Bill 574) with bipartisan sponsorship filed this session.

“That is a one-step-forward solution,” said co-sponsor Rep. Ashton Clemmons, D-Guilford. “We need some real honest feedback and thinking and work on what the child care system costs, and we need to move.”

Pre-K in the middle

Calls for increased pre-K funding, capacity-building, and expansion continued throughout the pandemic year as teachers found creative ways to connect with children and families.

NC Pre-K, the state’s public preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds, shifted to remote learning in the early months of the pandemic. Teachers maintained contact with families, yet some worried about students’ screen time and lack of social interaction.

In the fall, some pre-K students entered the program fully in person, others enrolled remotely, and others fell somewhere in between. Overall, enrollment dropped from about 31,000 children to 22,000, or from 25% of the state’s 4-year-olds to about 18%, said Susan Perry, chief deputy secretary of the state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). More than half of those children, Perry said, were learning remotely.

The program exists in public settings like school districts and Head Start programs, as well as private child care centers. Pre-K finds itself “not fitting entirely within either K–12 education or child care,” reads the 2020 State Preschool Yearbook from the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER).

The last year has raised new challenges of access and quality, the NIEER report says. In North Carolina, providers continued to confront pre-pandemic funding issues.

Providers across public and private settings struggled to maintain quality and reach eligible children in their communities. The state’s allocation covers about 60% of the cost of the program, leaving providers pulling from other funding sources to pay teachers, provide transportation, arrange before- or after-school care, purchase materials, and find facilities that meet the program’s standards.

Many local leaders, from superintendents to Smart Start employees to child care advocates, are pushing for universal pre-K.

In Polk County, where leaders said pre-K reaches 75-85% of the county’s 4-year-olds annually, the program exists solely in public elementary schools. Administrators use funds from NC Pre-K, Head Start, Title 1, an Exceptional Children grant, a local county commissioner allotment, and parent fees to provide holistic student and family support.

“If you’re a 4-year-old in Polk County and you want to go to pre-K, we’ve got a spot for you,” said Polk County Superintendent Aaron Greene. Greene points to the district’s “robust pre-K program” as the source of later-grade achievement and says having pre-K within the district leads to alignment between early childhood and early elementary experiences.

In Sampson County, pre-K exists within public schools and Head Start programs. The county was reaching 50-75% of eligible children in 2017. Kelly Batts, assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction in Clinton City Schools, said the district pulls funding from an Exceptional Children’s grant, Title 1, and local dollars to serve children.

“I could see why other districts, if you have an aging roof, or if you have more at-risk kids in high school, whatever it is, that you have to supplement with local dollars, at some point you’ve got to make a decision about, is it worth it?” Batts said.

In Pitt County, pre-K is housed in both public schools and child care centers. At East Carolina Kiddie College, a private center in the county, owner and director Tenisha McGhee said the state’s reimbursement rate is not enough to keep qualified teachers or provide full-day care that works with families’ schedules.

“With the NC Pre-K funds they do give us, it gets stretched very thin — very, very thin,” McGhee said.

Local providers say an increased NC Pre-K reimbursement rate would help them retain quality teachers and cover other costs. A group of business leaders pushing for pre-K expansion is also calling for an increased rate — as well as support for private providers to meet standards to house NC Pre-K classrooms.

In Forsyth County, where pre-K exists in both public and private settings, only about 27% of eligible NC Pre-K children were reached in 2019. A group of cross-sector leaders called The Pre-K Priority is pushing for universal pre-K, originally inspired by Durham Pre-K’s approach.

The city and county council established an early childhood education task force to explore how best to reach that goal. Bob Feikema, president and CEO of Family Services, said the county’s inability to reach more children is linked to private centers not having adequate subsidy funding.

“I think all of those things are intertwined … that’s why we, as a group that was focused on pre-K, have seen the market rate to be a critical issue for pre-K even though it addresses a broader range of children. Unless we have a market rate that sustains and supports high-quality programs, period, we’re going to have a more difficult time having a high-quality pre-K system.”

Bob Feikema, president and CEO of Family Services

Biden’s pre-K proposal, presented to Congress in April, would provide free pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds. The White House’s statement says the $200 billion investment would “prioritize high-need areas and enable communities and families to choose the settings that work best for them.”

As state and federal policymakers see pre-K expansion as a unique area of bipartisan agreement, Wuori said, “The devil is in the details.”

Some school districts would prefer having pre-K in their buildings or districts for better alignment to early grades. Other early childhood advocates, like Wuori, say a mixed delivery approach is important to uplift programs and the workforce in earlier settings.

Placing too much public pre-K in school districts, Wuori said, could make infant and toddler care even less stable. Since infant and toddler care is the most expensive to provide, centers are often only able to make ends meet with tuition and public dollars from preschool-age children.

“States will really have to grapple with this if more federal funds come down for pre-K. It remains true that putting too much of that resource into the school district sector poses a really existential threat to the stability of child care and the availability of infant-toddler care.”

Dan Wuori, senior director of early learning at The Hunt Institute

Catching up and going forward: A child-centered approach

Henrietta Zalkind, director of the Down East Partnership for Children (DEPC), has both local and statewide viewpoints into the future of early care and education, and what this pandemic means for children and families.

In Edgecombe County, Zalkind and the partnership’s staff have been stuffing backpacks full of supplies and activity instructions that will go home to 1,000 families. This year, they said they’re reaching more than any other with online tutorials that tell families what a confident kindergartner looks like.

Zalkind, who also served on the Governor’s Leandro commission, thinks of kindergarten readiness as the condition of both children and schools and as a process that starts with a healthy pregnancy.

“How do you launch every child as a lifelong learner?” she said.

Zalkind said this is the question the system of early care and education should be centered around answering, this fall and beyond. That will also inevitably raise third grade reading proficiency, she said, an indicator state leaders have been aiming to increase in the last 10 years with a renewed strategy this year to align reading instruction with research on how children learn to read.

“It is a moment to really look at how we use our public funds to invest in a 0-8 continuum of early ed that makes sure that all kids are starting school ready and confident, but that they are reading on grade level by the end of the third grade.”

Henrietta Zalkind, director of the Down East Partnership for Children (DEPC)

Kindergarten readiness will look different this year for both children and schools. Last school year, kindergarten saw a larger decline in average daily membership (ADM) — about 16,000 fewer children — than any other grade. An NWEA Research report released in April provides some guidance as to how educators can prepare for the kindergarten class of 2021.

The report suggests expecting greater age differences in both kindergarten and first grades, preparing for wider skill disparities of children coming from a variety of settings, using summer to get kids ready, and using data to inform decision-making.

DHHS Chief Deputy Secretary Perry said the department is planning to use federal relief funds for a summer learning program and considering allowing some students who participated in NC Pre-K remotely to re-enroll for another year.

For students of all ages in public schools, the legislature recently passed a law, now signed by Cooper, requiring districts to offer a summer program that lasts at least 150 hours or 30 days to address pandemic learning loss. The priority is for students who are considered at-risk.

Addressing children’s social, emotional, and mental health needs will be critical as children return to learning environments, said Hughes, executive director of NC Child.

“When we have all these young people coming back in the fall, we really, really need health and mental health supports in the schools to support their learning. It’s going to impact their ability to achieve and to learn.”

Michelle Hughes, executive director of NC Child

Increased family engagement

Early educators and administrators have found new ways to connect with children and families — some of which they want to carry forward.

From texting to calling to video-chatting to posting on a school-based platform, educators — especially those dedicated to remote learners — learned new communication strategies and increased that communication.

“Our early educators feel like they are more connected to families than they’ve ever been before,” said Batts, the administrator in Clinton City Schools. “And I know that sounds maybe counter-intuitive, but they’re meeting virtually with students so they’re seeing their students’ dogs. Families are connecting while they’re in the mids0t of shopping. They are truly in their homes so much, and they feel like they know them so much more intimately.”

For in-person learning environments, parents were not allowed to enter the building to drop off their children, volunteer, or attend in-person events.

“It’s so hard because I’m very, ‘Come on in my classroom,'” said Ashley Marion, a pre-K teacher at Saluda Elementary School in Polk County. The district’s pre-K program normally includes home visits before the school year starts, which weren’t possible this year. Marion said she conducted parent conferences over the phone and through distanced conversations in the parking lot. She also sent pictures to parents throughout the day.

Virtual instruction, though not ideal for young children, also provides teachers with flexibility going forward during other types of school closures or student absences.

“I would still like to see some component for virtual opportunities, because I just think we live in a time where we need to try and be creative and meet the needs of families as best as we can,” said Yuvonka Davis, pre-K director in Greene County Schools.

Options that lift up all children

One of Zalkind’s pandemic lessons is a renewed focus on meeting children where they are.

“Any system has to shift as the context shifts,” Zalkind said.

Moving forward will take asking families what they need and meeting those needs, rather than prescribing a certain program or environment, she said. Meeting children’s needs could look like parenting classes, a home visiting program, a connection to other public programs like food or health services, a play-based group, a child care center or home, or a pre-K program.

With an influx of federal money, planning for the state’s use of the Child Care and Development Fund for the next three years, and a Preschool Development Grant, Zalkind says “this is a real moment” for early care and education in North Carolina.

“We have to look at those pieces of the puzzle but we have to look at it through an equity lens — and not on a really academic conversation — we have to look at it through a lens that a parent looks at it through: ‘What do I need to have my child be successful?'”

Henrietta Zalkind, director of the Down East Partnership for Children (DEPC)

That means reversing trends for parents, children, and educators who are not benefitting from the current system, particularly communities of color, she said.

A national report from several research and advocacy organizations released in December takes a racial equity lens to early care and education, offering “14 Priorities to Dismantle Systemic Racism in Early Care and Education.”

Home-based facilities have stayed open at especially high rates through the pandemic and, the report says, are important settings to invest in going forward. They are especially important in rural areas, in providing infant and toddler care, and in providing culturally responsive learning for children of color.

Some North Carolina early childhood advocates have rallied together over the last year to link the nation’s reckoning with racism following the murder of George Floyd to early learning experiences. A data point they point to as one symptom: Black preschoolers are three times as likely to be suspended or expelled from public preschool programs than their white peers.

“If we understand that it really is about children being able to thrive … then it doesn’t matter the setting, it just means that we have to make sure the setting meets whatever standards, we have to make sure the workforce meets whatever standards, and we pay them accordingly.”

Iheoma Iruka, research professor of public policy and the founding director of the Equity Research Action Coalition at Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute

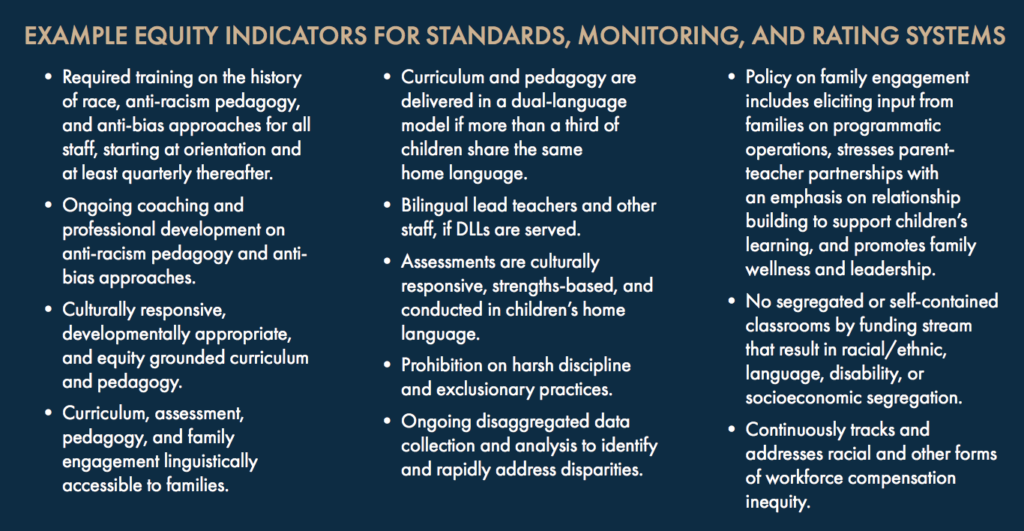

Iruka said those standards, as well as the state’s quality rating and improvement system, should reflect what matters for children. The report recommends equity-centered standards below, including “prohibition on harsh discipline and exclusionary practices”:

Moving towards an equitable early learning system, Iruka said, will require being honest about historical racism and creating accessible, affordable options that reflect communities’ needs.

“I do think it’s on us as a state, if we’re trying to do better and be better, is to do it in a way that is mindful of issues of equity, issues of systemic racism, and just issues that really center children,” Iruka said. “I think that’s something that we have to continue to push on — how do we make sure that children’s experiences are full, that they’re free of bias, that they provide opportunity for their voices? Let’s not do things that make adults happy. Let’s do things that we know matter for children.”

Find the rest of EdNC’s special report on this pandemic school year here.