Nestled on the fourth floor of a downtown Indianapolis mall, Purdue Polytechnic High School is unassuming from the outside — but within its walls is a school like few others.

Students learn design thinking principles as they tackle real-world challenges with industry partners. There are no set courses, like English I, or class periods — instead, artificial intelligence creates unique schedules for every school day that match students and teachers based on need. School faculty are called “coaches” instead of “teachers,” and students are urged to explore their own passions through project-based learning. Roughly 18 subject-neutral core competencies are used to assess student knowledge on a mastery scale. And, graduates who meet certain academic benchmarks are guaranteed admission to Purdue University.

Purdue Polytechnic High is a charter school, which means it’s publicly funded and privately operated. The school is run by a nonprofit board and was authorized by Indianapolis’ Mayor’s Office of Educational Innovation. But Purdue Polytechnic High is also part of Indianapolis Public Schools, the local public school district, as a member of the innovation network. The school is free to attend for any student who is admitted via a lottery system. And, after opening the doors to its first school in downtown Indianapolis in 2017, Purdue Polytechnic High expanded to a second campus in north Indianapolis this fall.

Learn more about Indianapolis’ innovation network schools in this Weekly Insight.

A new recipe for a school model: Innovation network schools in Indianapolis

Purdue Polytechnic High School, downtown campus, 2018-19 facts

– Enrollment: 260 students (ninth and 10th grade)

– Student ethnicity: 35% black, 33.5% white, 21.5% Hispanic, 7.3% multiracial, 2.3% Asian

– 60.4% of students qualify for free- or reduced-price meals

– 16.5% special education students

– 3.7% English Language Learners

Reimagining high school

In 2015, there were roughly 48,000 Indiana high school seniors who took the SAT. Out of those, there were just over 250 underrepresented minority students who met Purdue University’s average incoming SAT score.

That’s according to Scott Bess, head of schools for Purdue Polytechnic High, who said this staggering statistic came as a wake up call to Mitch Daniels, president of Purdue and former governor of Indiana.

Bess said that many of the university’s minority students come from out-of-state or out-of-country — and that those students tend to leave Indiana after completing their degrees. With large companies like Salesforce and Infosys setting up shop in Indiana, the labor market in the state was ripe for highly-skilled STEM workers.

“So Purdue and President Daniels said instead of pointing the finger at K-12 and saying, ‘you guys need to do better,’ he said look, why don’t we do something?” said Bess. “He looked at it and said, if Indiana is going to continue to thrive, we have to have all types of students being successful.”

At the same time, one of Purdue’s colleges — Purdue Polytechnic, formerly the College of Technology — revamped its curriculum to focus on project-based learning and hands-on instruction. The college had a need for incoming freshmen who had similar hands-on STEM experiences in high school.

And so the idea for Purdue Polytechnic High — a school that would increase the pipeline of low-income, underrepresented minority students interested in STEM to Purdue and other universities — was born. At the time, Bess worked for Goodwill Education Initiatives. In that role, he opened Excel Centers — tuition-free high schools for adults who had previously dropped out. The schools offered things like child care assistance, life coaches, and an accelerated curriculum to award high school diplomas in only a few years. The success of that experience resulted in Bess being selected as the head of schools for Purdue Polytechnic High.

In 2016, Bess and Shatoya Jordan, founding principal of Purdue Polytechnic High’s first location, spent a year planning for the school to open as part of the Innovation School Fellowship through The Mind Trust, an Indianapolis-based nonprofit that supports the launch of innovation network schools, among other things. Fellows receive a salary and benefits during that time, along with coaching, professional development, and stipends to travel — allowing them to fully dedicate one to two years to planning and launching an innovation network school. In 2017 and 2018, Bess and Keeanna Warren, founding principal for the second location of Purdue Polytechnic High, also participated in the Innovation School Fellowship.

Their first step in planning the school was listening. Bess and Jordan spent the year talking to Purdue University faculty, local employers, prospective students, and recent high school graduates. They asked faculty and employers what they were looking for in future students and employees. They asked prospective students what kind of high school experience they wanted to have, and they asked recent high school graduates what they wished high school had been like.

And the answers to those questions had a lot of commonalities. Every stakeholder, from the middle school student to the future employer, wanted high school to incorporate project-based learning where students work in teams to solve complex problems. They wanted those projects to have real-world applications, and they wanted the high school experience to build non-cognitive skills like cooperation and empathy.

As Bess and Jordan visited other schools across the country through their fellowship, many people agreed — sure, in an ideal world, that’s what high school should be. But there was always a “but.”

“It almost always boiled down to: There’s only so much time in a day, you only have seven periods a day, six hours a day, you only have 36 weeks … you have these rules, you got all this stuff,” said Bess.

To create the hands-on, STEM-focused school that Bess and Jordan imagined, the school day would have to be redesigned radically differently.

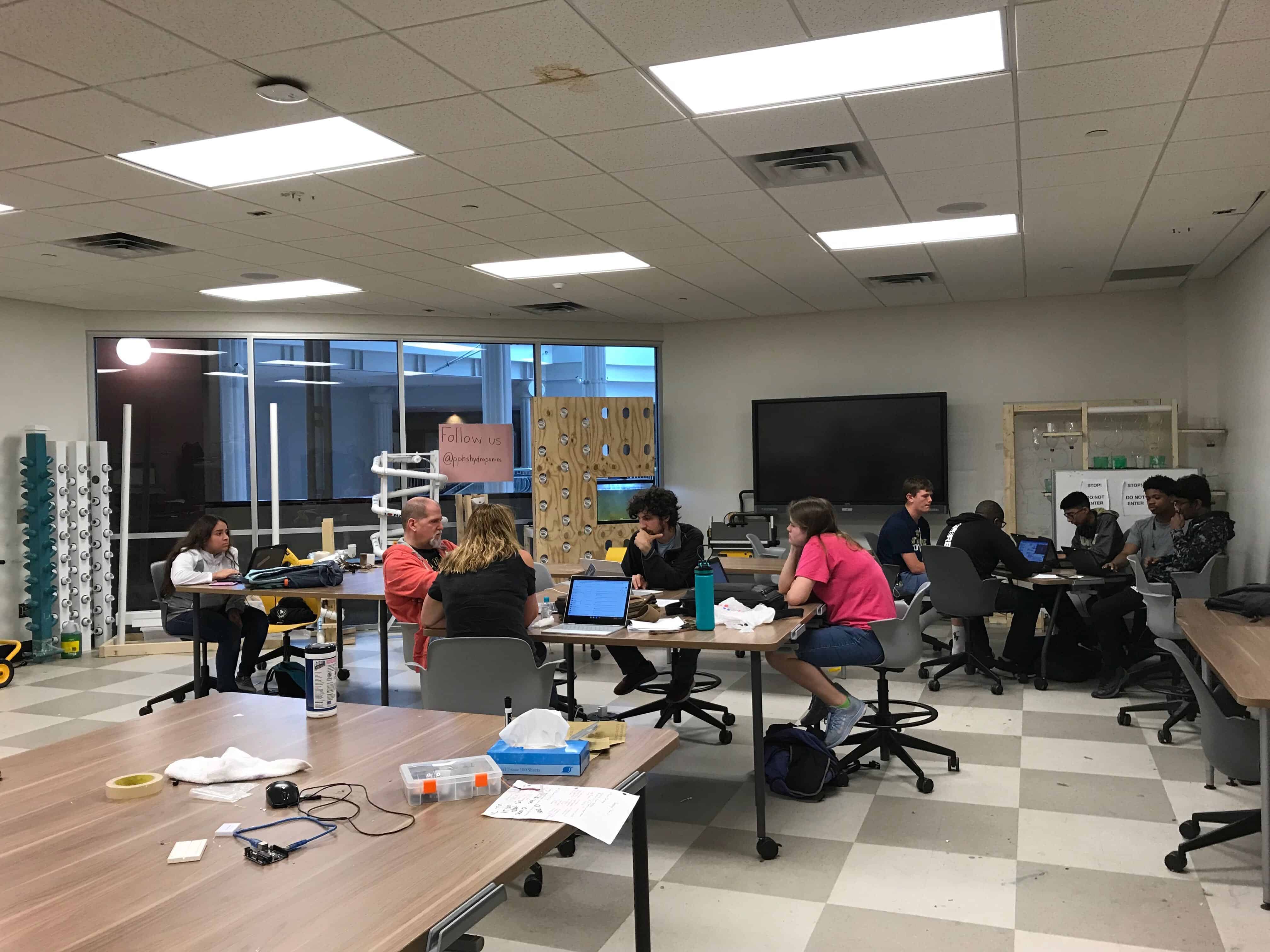

Centering the school day: Hands-on STEM experiences

Many traditional schools operate using a master schedule with set class periods in which students are assigned to different courses and teachers. As Bess and the team considered the fundamental design of Purdue Polytechnic High — which included things like students tackling big challenges, partnering with employers outside of the school building, and having academic instruction integrated into projects rather than separate courses (like English I and Algebra I) — it became clear that the master schedule system was not going to work. So they scrapped it.

Instead, students spend the first 45 minutes of every day in personal learning communities, similar to homerooms. These small classes of students check in with their coach and engage in team building and social emotional learning activities. Then, students spend the rest of the day in a blend of personal learning time where they might complete self-directed work on a challenge or online coursework, and in team time where they make group progress on design challenges.

During freshman and sophomore year, the focus of the school experience is exposing students to as many different career clusters and problem-solving techniques as possible. Students engage in 12 big design challenges, each of which includes an industry partner. Each challenge lasts six to seven weeks and includes time when the industry partner comes to the school and when students visit to the industry partner site.

During a recent project, students partnered with Corteva, an agriculture chemical company. Their challenge: How do you feed 9 billion people on the planet by the year 2050? Students talked to Corteva lab works, chemists, biologists, grocery store employees, and landfill workers to get a sense of the issues involved in tackling the challenge. Then, they approach the challenge through design thinking, including background research and instruction in empathy. Ultimately, students break into teams, decide what problem within the challenge they want to attack, create and iterate solutions, pick a solution, prototype it, and pitch it. The industry partner is brought back in at the end to judge the final pitch contest.

Outside of these design challenges, students receive core academic instruction through online modules to learn the basic building blocks of certain subjects — like the parts of a plant cell or how to solve linear equations. While Bess doesn’t believe online instruction is a perfect solution for all students, he sees it as a strategy to increase the amount of time students are spending on tackling design challenges.

“We firmly don’t believe that that’s the best way to do it or that it’s great for all students. The premise is, if we can get good enough instruction for most students, then that frees up our most valuable resource — our humans — to do these really cool projects and applications of knowledge,” said Bess.

That means if only 30 out of 200 students need extra instruction on the parts of a plant cell after completing the online module, a coach can work with directly with them while the other 170 students work with coaches on big design challenges.

Last school year, Bess learned that having no structure to the school day was difficult and hard to keep track of with more than 200 students. So, this year, Purdue Polytechnic High launched a new scheduling system that dynamically schedules each students’ week depending on what they’re working on and what instruction coaches are offering. In the previous example, the system would assign those 30 students to receive extra instruction on the parts of a plant cell from the coach who is best suited to provide that instruction. Then, students would log in to the scheduling system and select the course time and date that works best for their schedule.

The goal: Students are never sitting in a classroom bored because they already understand the material or confused because they don’t understand it at all. Instead, students who need more help get it, and students who are ready to move on have the chance to dive deeper into an aspect of a project that they’re interested in. The process requires flexibility on the part of both the students and teachers — who often don’t know what they’ll be providing extra instruction on until the week before.

Students are assessed on their mastery of roughly 18 subject-neutral competencies like data analysis and the writing process The data analysis competency might show up during a science lab, while writing a research paper for English, or while performing a math equation. Teachers assess students’ mastery of these competencies, but that doesn’t mean they’re always giving out tests. For example, students can show evidence of mastery on their employee ability competencies by having the manager of their part-time job or internship speak to their work performance.

Grades are a combination of students’ performance on online modules and their mastery of the competencies. Those grades show up on the students’ transcripts just like they would at a traditional high school — with letter grades for subjects like Biology or Algebra 1. But, because the school is mastery-based, those grades are in flux until the student graduates, since they can progress in their mastery of any of the competencies over the course of four years.

“It’s a four-year grade because no college cares when you’re learning it — they care that you know it,” said Bess.

When Purdue Polytechnic High graduates its first class in 2021, another unique aspect of the school will come to fruition: direct admission into the Polytechnic College at Purdue. To qualify for that admission, students have to meet a minimum score on the SAT or ACT and have at least a 3.4 GPA. Bess is working to include some of Purdue’s other colleges in that direct admission agreement, and expects that the College of Education will also sign on.

This college guarantee comes back to what Bess described as the mission of the school — to take students who probably wouldn’t otherwise go on to a four-year college or university or pursue a STEM field — and redirect their path. The school aims to serve low-income, underrepresented minority students, which is made easier by the school’s inclusion in the innovation network.

That status within Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) allows Purdue Polytechnic High to visit IPS middle schools and talk directly to students, parents, and teachers about their model and the type of students they want to serve. It also allowed Purdue Polytechnic High to use IPS’ food services. Instead of school buses, students receive public transit bus passes.

“We’ve been doing high school the same way for decades. And if we simply tried to do a high school in the same way, with the goal of changing those outcomes, it’s probably not going to happen,” said Bess. “And so our premise was we had to do something radically different to change the outcome that’s been fixed for decades.”

The results

In Indiana, new schools are allowed to waive receiving a school performance grade of A-F during their first three years — something Purdue Polytechnic High opted for. With ninth, 10th, and 11th grade students at Purdue Polytechnic High’s downtown campus this year and a freshman class beginning at its second campus, data on the schools is limited.

However, Bess is encouraged by initial test results thus far from the school’s first campus. Looking at preliminary results from ISTEP 10, the state test for sophomores, Bess said Purdue Polytechnic High students scored at or above the state average for passing rates in English, math, and on both tests. Beyond test scores, Bess also sees high levels of student and staff retention as a sign of success.

And, at the end of the day, Bess said he is more interested in students mastering competencies than achieving high standardized test scores. When students leave the school, they’ll have four years of experience working on project challenges, working in teams, managing their own schedule, and managing their personal learning time — things that Bess sees as crucial predictors of success in college.

“The point to us was, we could do all these other really interesting things — the projects and the competencies, and really focus on the things that we think matter — and be at least as good as everybody else,” said Bess.

The Mayor’s Office of Education Innovation, Purdue Polytechnic High’s charter authorizer, also holds the school accountable through an oversight process that considers academic performance, school finance, and governance, along with a site visit during every other year in the school’s initial charter term. In 2017-18, Purdue Polytechnic High met or exceeded all of the standards it was assessed on, including the standard for strong school attendance with a 95.6% overall attendance rate, standards for short-term and long-term financial health, and standards for school leadership and board governance. During its second year review in the 2018-19 school year, Purdue Polytechnic met all standards of the site visit, including things like high-quality curriculum and using standards and assessments to inform and improve instruction.

After opening a second campus this fall, Bess said there are plans to open a third next year, which will likely be located outside of Indianapolis. Some challenge the decision to open new schools despite not knowing the true impact of the model on students. While Bess acknowledges the full impact of the school is still unknown, he’s not willing to sit around to find out.

“We don’t know for sure that our students are going to get into college and be successful. But what I do know is that students staying in traditional high schools — particularly lower-income students of color staying in a traditional high school — we know what those outcomes are,” said Bess. “What I know is we’re not going to be worse than that. So it has a chance to be better. And I’m willing to take that risk.”