|

|

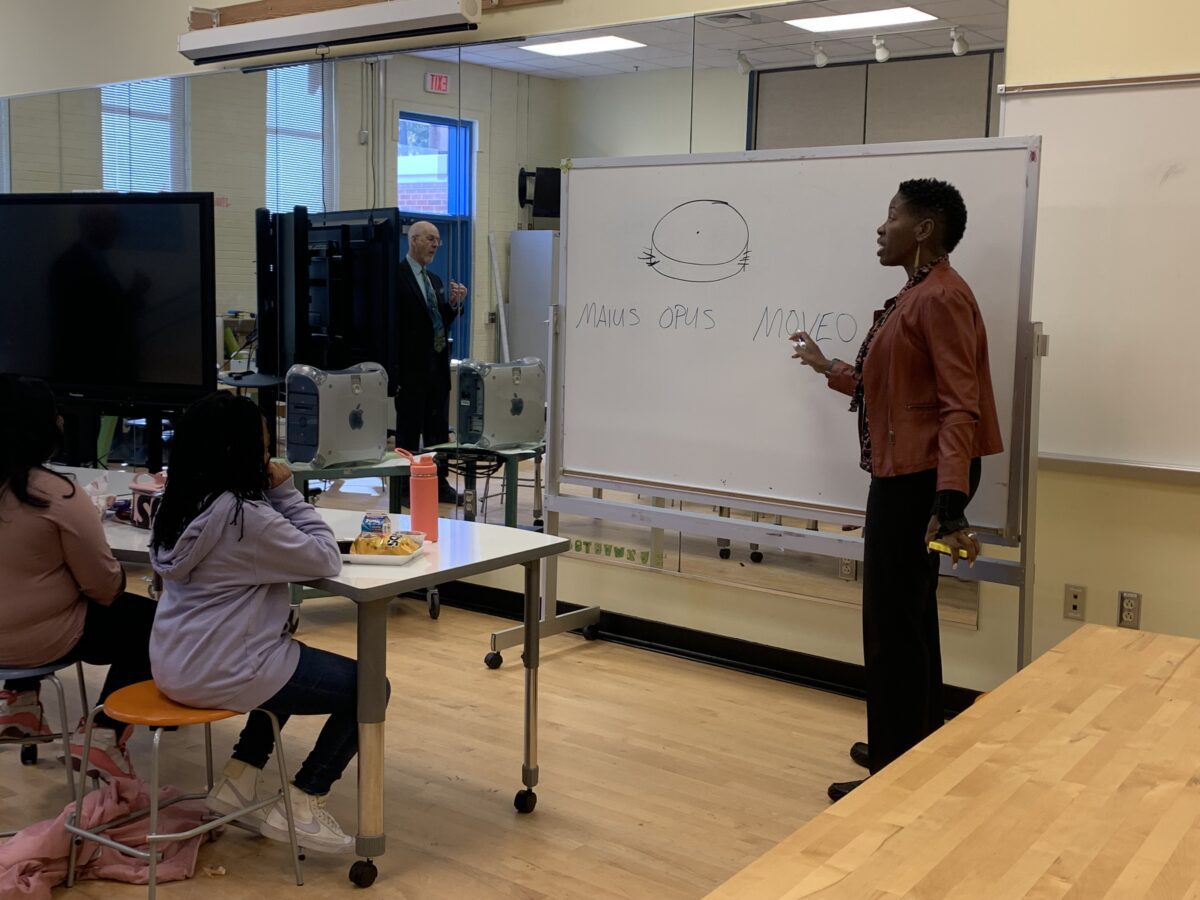

Before Dr. Annice Williams became principal of Bugg Magnet Elementary School in Wake County, the school did not have a mascot.

Now Bugg-E — the green lightning bug-robot hybrid — is not only a symbol of the school and its innovative tech mission, but William’s quest to foster shared collaboration on ideas and students’ success.

Lifelong educator

From the time Williams started kindergarten in Robeson County, education met her at every corner.

“The neighborhood I grew up in, every house had at least one educator. Many of the families were like ours where both parents were educators,” Williams said. “My family is my community, so it’s kind of the only thing I ever considered.”

Williams is not a novice to the importance of the sciences. A North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill alum, the administrator strives to give back to the community.

When she is not fulfilling principal duties, she is an adjunct instructor for East Carolina University’s international programs. She meets with students every week to show them the ins and outs of school administration.

“I think the thing I appreciate the most about Annice is that she has a laser-like focus on school improvement. And she doesn’t make it about her. She makes it about the systems and processes in place that propel the whole school forward,” Elena Ashburn, central area superintendent for Wake County Public Schools, said.

In her three years of experience as a teacher and over 20 years of experience as an administrator, she has found that the one of the greatest challenges she has faced is helping others adapt to change.

Her journey at Bugg began in June 2020, just a few months after the COVID-19 pandemic began. While managing the transition from virtual learning back to in-person classes, she realized that it took a team effort.

“Even once the students were coming back into the building slowly on a rotation, and then the parents were coming back into the building, you know, we had to figure out new ways of doing things,” Williams said. “But that’s about trust and getting input of all those voices.”

The pandemic also exacerbated the teacher shortage. According to Williams, she used to be able to expect 40 applications in one month after posting a job. Yet recently, she said, they have been lucky to get seven.

“All employers are trying to hire, and I think it’s impacting schools even more because these are not jobs that you can just fill in with just any person, and it takes a certain level of skill. It takes a certain type of personality. It takes a certain heart and a certain commitment,” Williams said.

However, Williams said that Bugg is lucky to have a good balance of new and experienced teachers.

There is one concern that newer teachers have that Williams had not experienced in the past: safety from school shootings.

Williams said that if the school builds mutual trust among faculty, parents, and students, they can find a way forward together.

“(Students are) growing up in a different time. And there are different, you know, the influences of technology and the influences of school safety concerns, or all these different things,” Williams said. “And so, as adults, we bring these expectations to the work, but what the work actually is has changed so much from the time that we experienced it on the other side as students.”

Zoom out, zoom in

On any given day, Williams begins by greeting students, meeting with staff to put out fires, and “whatever else the children have in store for her.”

Williams said that the great thing about operating a school of less than 300 students is that it allows them to look closely at their data and plan on the individual level.

“When we see patterns that we should not see — if it’s patterns of achievement, by gender, by ethnicity, by IEP status, special education status — then we’re working with individual students. We’re planning enrichments and supports for individual students,” Williams said, “but then we step back, zoom back out, and look at our school data and look at what the patterns are.”

They don’t only look at achievement data, but “perception data.” Another key element at Bugg is family engagement. Williams said that they distribute family surveys as a district and school as a line of communication to see how families across different demographics feel that their student is being served.

“It’s that constant process of zoom out, zoom in, zoom out, zoom in. So once you zoom out and see the pattern, then you dig in and look at the people and figure out what their experience has been and what adjustments you can make to it,” Williams said.

Williams said that despite being able to mentor others at this point in her career, she still learns a lot from parents and younger principals in her professional learning community.

Years ago, she said she had difficulty with the parent of a student that was in special education. She was able to earn the family’s trust once she realized that the parent’s concerns were coming from a place of love and urge to protect their child.

“If we can stay in it and stay focused and not take it personally, see the parent for what they are — a parent who is concerned about their child,” Williams said, “then you can make that progress.”

Within two years, the parent was comfortable enough with the Bugg Elementary staff that they did not feel as much of a need for outside facilitation during the child’s IEP meetings.

Bugg Magnet Elementary School’s smaller student population allows teachers to have a more attentive and detail-oriented approach to student achievement. From Williams’ perspective, their school has all of the tools at their disposal to help their students succeed, but their utilization is the key.

For example, they have a math program called DreamBox Learning that allows students to practice while it adapts to their skill levels. Wiliams checks in with teachers to talk about how they structure their use of the program, or whether they incorporate the program into class time to get the most of out it.

“In my experience, lots of different programs and platforms can get results, but they all have to be used effectively in line with how they’re designed and in with an eye to what the data says about the results that you’re getting. So I think it’s about the fidelity and the quality of usage that ends up making the big difference and achievement,” Williams said.

The same thing goes for when teachers are in their professional learning communities.

“When folks go into PLC, they’ve got 75 minutes. How are they using the time? Is our school schedule structured so that teachers can get into that PLC in the time it starts, or are they losing 10 minutes because other folks aren’t in place to receive the students?” Williams said.

“I have been working with Dr. Williams for years now at three different schools, and I think she’s an outstanding person,” Geneva Hill, a substitute teacher that has worked in Wake for over 18 years, said. “She’s very patient with you. She is willing to work with me, and I’m learning from her. I enjoy being around her.”

Representation

Williams said that one of the biggest mistakes that leaders can make is making themselves responsible for everything alone in a school environment.

She said there is no way she could have survived her first year on the job without counting on other people.

“When I was a first-year principal, I actually took over near the end of the school year and I didn’t have an AP (assistant principal). I was the only administrator, and I was learning to do the job. And even though APs and principals work close together, the principal job is just different,” Williams said.

As Williams learned the value of the principalship and collaboration, she learned the same of recognition.

In 2022, Williams was selected as Wake County Principal of the Year after becoming a finalist four different times. Despite hearing encouragement from her peers, she felt discouraged because she didn’t see many other Black women being recognized.

“One of the reasons that I raised that point about Black women, particularly in the principalship, is because over the course of my career, what I have noticed is that Black women in the AP position are the ones who get a lot of attention, respect, recognition, but many of those Black women go on to be principals and then are not highlighted in the same way,” Williams said.

Williams said from her perspective, Black women are more likely to become principals at Title I schools, where there is a higher percentage of low-income families and students tend to have lower achievement rates.

However, Williams said that should not invalidate the level of work that they put in.

“I thought it was important because we say all the time for the kids, representation matters. When kids come into school, they want to see people that look like them, leading and teaching and directing,” Williams said.

Williams said that she does not want herself or anyone else to be recognized as a great principal only for the sake of representation or imagery.

At the conclusion of her career, she wants to be remembered as an equitable leader.

“I want to be the leader that is there for every single person, for every single person to actually believe they can actually trust me, and believe that I am truly invested in their success and their positive experience and the school that I’m part of,” Williams said.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article stated that Dr. Williams was nominated for Principal of the Year four consecutive times. It was on four different occasions.