This is the fourth article in a series on faculty pay at North Carolina’s community colleges. Click here to read the rest of the series.

“For the past 60 years, North Carolina’s community colleges have consistently received $.08-$.09 of every dollar that the state invests in education. This must change if our state expects us to attract and retain faculty that will determine the quality of our future workforce.” – Garrett Hinshaw, president of Catawba Valley Community College

Concern about low pay for community colleges instructors is not new. In 1989, the Commission on the Future of the North Carolina Community College System warned of “a crisis in faculty and non-instructional salaries” and of how “low salaries in the community colleges have contributed to an erosion in faculty morale in the system and losses of talented faculty to industry.”1

In the late 1980s, the average salary for a full-time community college instructor in North Carolina was $22,600 (the equivalent of $33,556 in 2019).2 That average was 20% lower than the regional one and those posted in all but one other state.3 As is true today, the Commission noted a gap between the state’s low ranking on full-time community college faculty pay and its comparatively higher rankings for full-time pay of both UNC instructors and public school teachers.4 The community college system of the 1980s also received, as is the case today, the smallest slice of state education spending, leading to fears about “the system’s ability to maintain state-of-the-art instruction,” especially in expensive technical fields.5

Past progress followed by a decade of stagnation

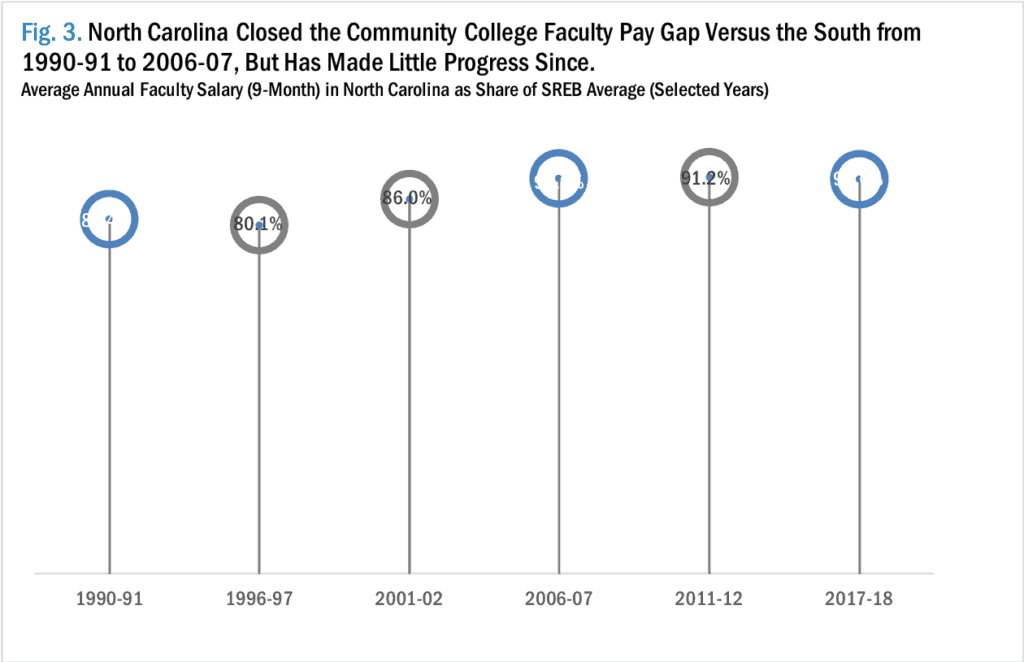

The Commission called for the State Board to “set a goal to raise salaries for faculty to the median level in the Southeast by 1992 and the top quartile of the Southeast by 1995.”6 A review of historical SREB data shows that North Carolina failed to meet that challenge; as of 2017-18, in fact, North Carolina has never posted a median salary for full-time community college instructors equal to the regional figure, let alone one that would fall into the top quartile.7

North Carolina nevertheless has made progress in improving the salaries paid to community college instructors, at least relative to the region. The gap between the state’s average full-time community college faculty salary and that paid in the SREB region narrowed by 30% between 1990-91 to 2017-18 (Fig. 2). Over that span, the typical community college instructor in North Carolina went from earning $0.81 for every $1 paid to the typical SREB instructor to earning $0.91 for every $1 paid to the typical SREB instructor.8

All of that improvement, however, occurred from 1990-91 to 2006-07, which is when average annual full-time faculty pay in North Carolina first equaled 91% of the regional figure. In the subsequent 11 years with data, no further salary convergence has occurred.9

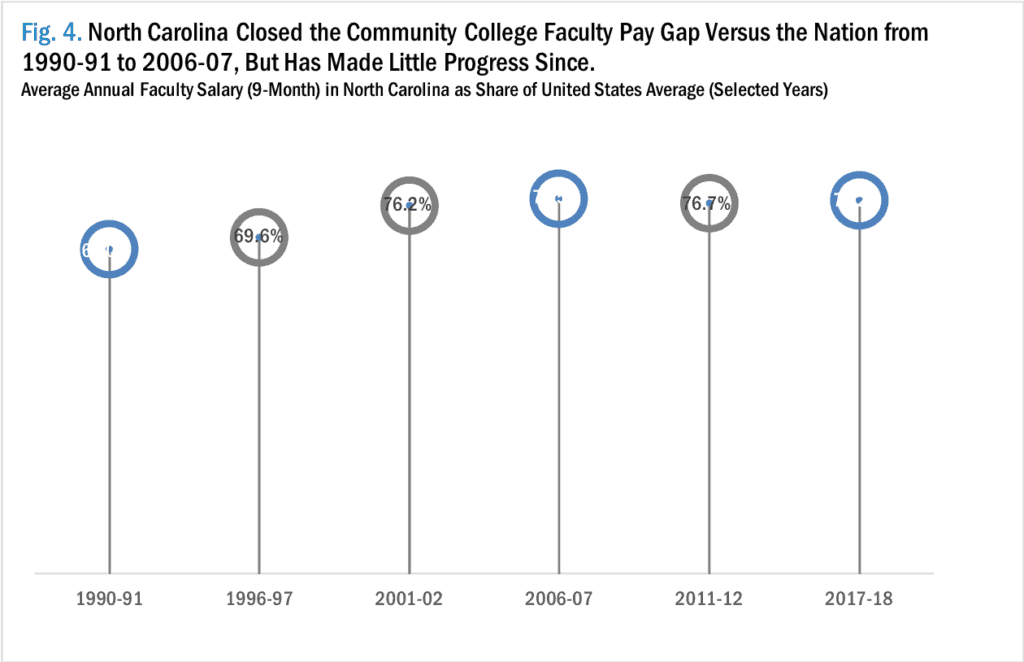

In contrast, North Carolina has not proven as successful at narrowing its salary gap relative to the nation. The typical community college instructor in North Carolina went from earning $0.67 for every $1 paid to the typical instructor in the United States in 1990-91 to earning $0.77 for every $1 paid to the typical instructor. Despite some minor fluctuations, the state-national pay gap basically has not narrowed since 2006-07 (Fig. 3).10

Multiple causes of stagnation

North Carolina’s lack of progress in improving faculty pay over the last decade is attributable to multiple factors, including the impact of the “Great Recession,” and the relationship between enrollment patterns and funding levels.

As explained in prior research from EdNC, North Carolina is required to pass a balanced budget, and during recessions, the state often is squeezed between reduced revenue collections and the need to fund non-discretionary services such as public education.11 One area that can be cut is higher education, especially since tuition increases can offset some of the reductions.

North Carolina did just that following the onset of the “Great Recession” in 2007. When measured on an FTE basis, total state support for North Carolina’s community college system fell by 16% between 2007-08 and 2016-17, falling from $5,830 per FTE to $4,891, after adjusting for inflation.12 The tuition charged for each credit hour taken by an in-state curriculum student, meanwhile, jumped to $76 from $42 (or $51 after factoring in inflation).13 Put differently, total annual tuition for a full-time, in-state student, after adjusting for inflation, went from $816 to $1,216 in roughly 10 years. Remember, too, that tuition excludes institutional fees and living costs, both of which add markedly to the total cost of attendance.

In last year’s legislative session, there was hope that community colleges would receive a significant increase in funding. The Republican-controlled General Assembly passed a budget that included funding for faculty salary increases, although the minimum salary for faculty remained the same. Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, vetoed it due to disagreements over priorities, and the legislature failed to override that veto.14 The legislature and governor instead have agreed to several “mini-budgets” to fund some services.

Three of the mini-budgets pertain to the community college system.15 Combined, Senate Bill 61 and House Bill 111 provide $1.2 billion in funding for each year in the biennium.16 House Bill 226, however, specifically excluded community college personnel, including instructors, from the 2.5 percent salary increase granted to state employees in each of 2019-20 and 2021-22.17

Lastly, the ability of individual community colleges to provide additional faculty compensation hinges on the complex interplay between enrollment and funding. Given how the funding formula discussed earlier works, colleges can lose resources when enrollment falls, which tends to happen during economic expansions like the one that began in North Carolina in 2010. Systemwide enrollment indeed dropped for every academic year from 2010-11 through 2018-19 before rising by more than 4% in 2020-21, with 53 of the state’s 58 colleges posting gains.18 When enrollment falls, so does funding, which creates new challenges to raising faculty pay.

“Even though we’ve got a lot of flexibility and autonomy, if you’re facing a budget cut because of an enrollment decline, the classroom ends up being affected,” noted President McInnis of Richmond Community College.19 “So those faculty tend to not get raises they might otherwise get. And even though the salary may go up a little bit, it doesn’t reflect, in some cases, an increased workload. So, what you’ve seen in some places are overload is increased or not paid and compensated for.”