If he really wanted, William Leach’s son probably could have gotten into one of Charlotte’s early college high schools. Leaders at the two schools, focused on engineering and teaching, boast that the admission lottery cannot be gamed. But Leach is the principal of both schools, so his son might have found a way.

It wasn’t the right fit for him, though. Which is good, Leach says, because his children aren’t necessarily the students he’s after.

“I want the kids that this is a game changer for,” Leach said. “That no one else in their family has been here. No one else has had this opportunity.”

The schools, Charlotte Engineering Early College (CEEC) and Charlotte Teacher Early College (CTEC), both sit on the campus of UNC Charlotte, where students have the opportunity to obtain both a high school diploma and up to two years of transferable credits in five years.

Through honors and college-level coursework, the schools change the game for their primary targets: first-generation college students, at-risk youth, or students in search of accelerated courses. For local engineering businesses in the area, CEEC could help keep the future workforce local. At CTEC, the school has the potential to boost numbers amid teacher shortages, including for teachers of color who are perennially underrepresented at the front of classrooms.

Producing home-grown teacher talent

CTEC opened in 2017 and has amassed an enrollment of 148 freshmen, sophomores, and juniors in its third school year. If they take another 50 or so students next year, as is the goal, there will be almost 200 high school students exposed to the teaching profession at a time when public schools are reporting teacher shortages and the state’s educator preparation programs are reporting declining enrollment.

Leach admits that not every student at CTEC is interested in teaching. Neither the school nor the teacher college it partners with, UNC Charlotte’s Cato College of Education, expect a majority of CTEC students to enter the profession.

“If we can get 25 out of 50, they continue on to a college of education, that’ll be a success,” Leach said. “It’ll be a huge success, you know, and then if the other 25 major in criminal justice or something else, and they get access to college and get exposed to college credits, it’ll be a success.”

In fact, helping those hypothetical 25 students determine they do not want to be teachers is a win of sorts, too.

“Sometimes, if we’ve pushed them in another direction, that almost helps the investment,” Leach said. “So they don’t invest in an education degree, and then they’re not really interested in it and have to change gears later on.”

More coveted than the numbers are the demographics: 49% of CTEC students are African-American and 24% are Hispanic. Males, another sought-after demographic for ed prep programs, make up 24% of the school.

From Gov. Roy Cooper’s recent DRIVE Summit on increasing recruitment, development and retention of minority educators, to conversations and initiatives at the State Board of Education, there is a lot happening statewide to diversify the teacher workforce. Data presented in the issue brief for the DRIVE Summit shows that while 53% of North Carolina public school students were nonwhite in the 2018-19 school year, only 22% of educators were.

“And we’ve got them right here,” Leach said, pointing to minority enrollment at CTEC.

The entry point to the teacher pipeline is getting to and through college. Because of this, Shirley Prince, the executive director of the NC Principals and Assistant Principals Association, talked at the DRIVE Summit about the importance of encouraging a teacher-focus at CTEC and other early colleges.

“I agree,” said Ellen McIntyre, the outgoing dean at Cato. “It’s one of the most effective programs to help low and low-to-middle income people get a college degree, number one. For some of the folks that are in our early college for teachers, they wouldn’t even be able to get a degree without that opportunity. And then, on top of that, they encourage you to go into teaching.”

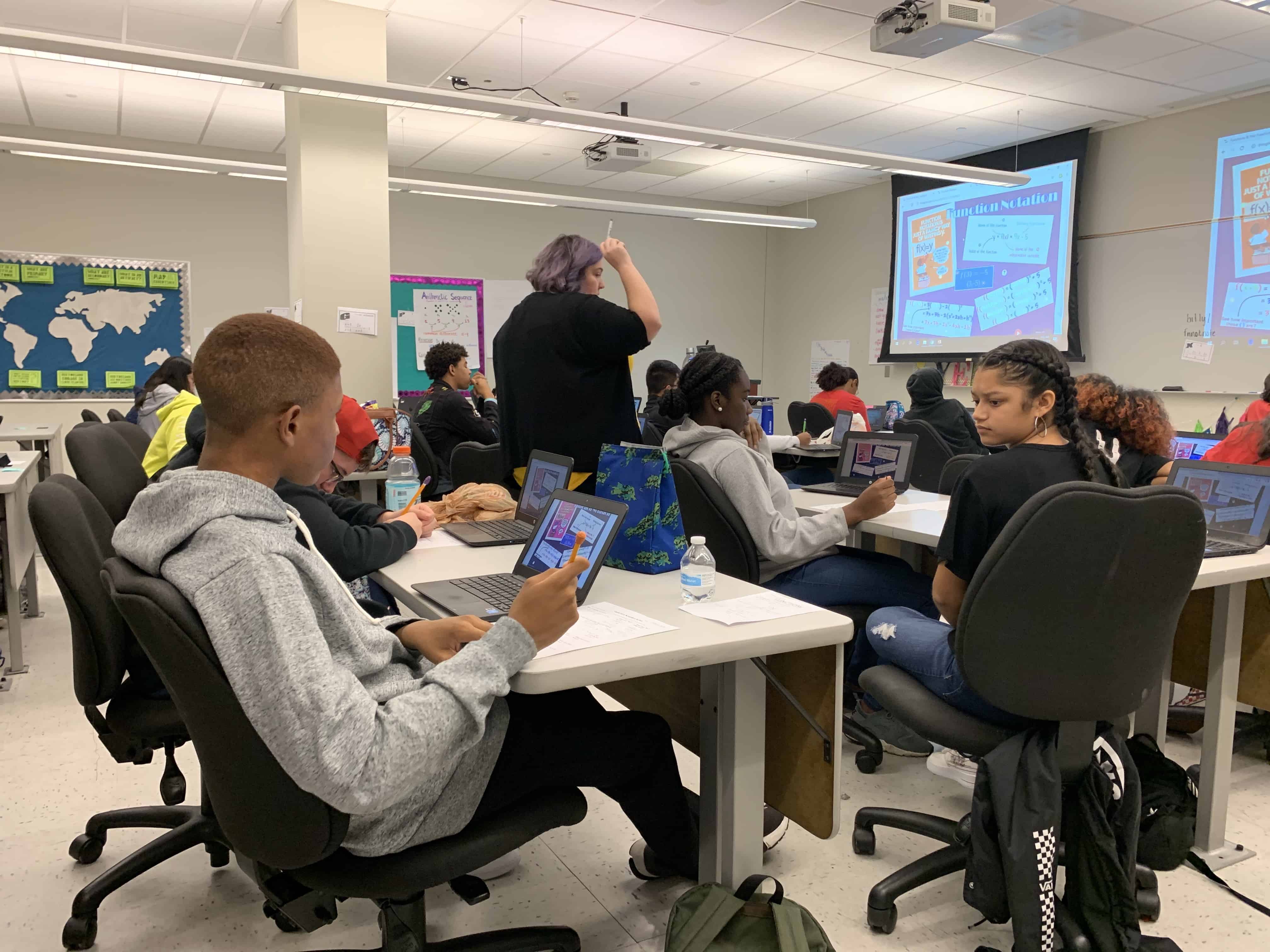

Leach says the exposure to what the profession is like has had an impact on his students. During freshman and sophomore years, students at CTEC focus on general, high school education. But in the last semester of sophomore year, they take their first education course. In the first semester of junior year, they take EDUC 1100, which is a clinical observation course.

“What we found was a lot of them weren’t really interested in teaching, but now that they’ve gone to clinical observations, they’re getting more interested,” Leach said of the first cohort of juniors at the school. “Ninth graders don’t know what they want to do, so you have to be open minded that they’re going to change their minds. And if they do change their minds, we’re not going to kick them out.

“They can still benefit from being in the program and getting the transferable credits. But a lot of them are going to this EDUC 1100 class and they’re getting exposed to education and their professors are doing a really good job. So they’re like, ‘Maybe I might want to be a teacher.'”

Boosting Charlotte’s engineering workforce

CEEC opened in 2014 in response to demand for a larger engineering workforce in Charlotte. In its first two graduating classes, 93 students earned their diploma. Last year, 29 enrolled at UNC Charlotte. For the university, it’s a boost for enrollment. For the city, officials are hoping it will eventually translate to a boost in the engineering workforce.

Just this summer, Charlotte secured the global headquarters of a Fortune 100 consumer products and engineering company. At CEEC, the idea isn’t to convert every student into a future engineer. Instead, it’s about exposure and providing them the tools to decide whether engineering is right for them and to flourish if they stay on that path.

Again, it’s not about the numbers, Leach says, as much as the quality of the student they put into the engineering field. For instance, of the 29 students that enrolled at UNC Charlotte, only eight stayed in engineering.

“Some people might say that’s a small number,” Leach said. “But for the engineering college, they’re like that’s eight students we didn’t have before. And they’ve seen that most of those students that are in this group, they come in really ready. I mean, they’ve had so much preparation that they’re ready for whatever they have to throw at them.”

By the time they’ve graduated, CEEC students will have taken about 20 college courses and two college engineering classes. But the engineering education begins in the very first semester of freshman year, and during their first two years at CEEC, students will take Introduction to Engineering Design, Civil Engineering and Architecture, Principles of Engineering, and Computer Science Principles.

Whether they stay in the field or not, Leach says, the students are receiving valuable, foundational skills and are meeting high expectations.

CEEC had a 100% graduation rate last year, exceeded academic growth, and its average SAT score was well above the state’s average.

“I think we’ve proven over five years that the investment is worth it,” Leach said. “Because the investment is probably at least double what you would commit to a typical student.”

College preparation for students

While Leach is excited about the engineering and teaching focus of his two early colleges, what he talks about most is the college preparation his students receive during their four or five years. Students at his schools take a demanding course load, and they get an opportunity to see what college classes require and what college life looks like.

“It gives that underrepresented minority group a chance to be exposed to college,” Leach said. “It’s shocking how many have never been on a campus. They don’t know what college looks like; they don’t know what it feels like. So to give them that confidence that, ‘Hey, this is something that I can handle.'”

In his first two graduating classes, he’s seen students move on to Cornell and Dartmouth. But several have stayed home, enrolling at UNC Charlotte.

“The key was a lot of those 30 were higher achieving and whatnot than UNC Charlotte would normally see,” Leach said, attributing their decision to stay on campus to a comfort level they achieved.

He’s hoping that the state and district will continue to invest in his schools. They’re running out of space and funds are tight, but he believes anyone that looks will see real value — particularly in the potential to boost local universities, the engineering workforce, and a diverse teacher pipeline.

“This has to look different than your traditional high school life,” he said. “It has to look different if we invest this amount of money and this amount of energy into it.”