This is the third article in a series on faculty pay at North Carolina’s community colleges. Click here to read the rest of the series.

“Any way you look at it, North Carolina is behind and falling fast in a region that trails the national average. It’s embarrassing to talk to policy makers and say ‘let’s raise salaries up to average.’” – John Gossett, president of McDowell Technical Community College

State appropriations are the main source of the salaries paid to community college instructors. In fiscal year 2019-2020, the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS) received an appropriation of $1.5 billion, of which $1.4 billion was allocated for instructional purposes.1 That appropriation accounts for a small share of total General Fund spending on education.

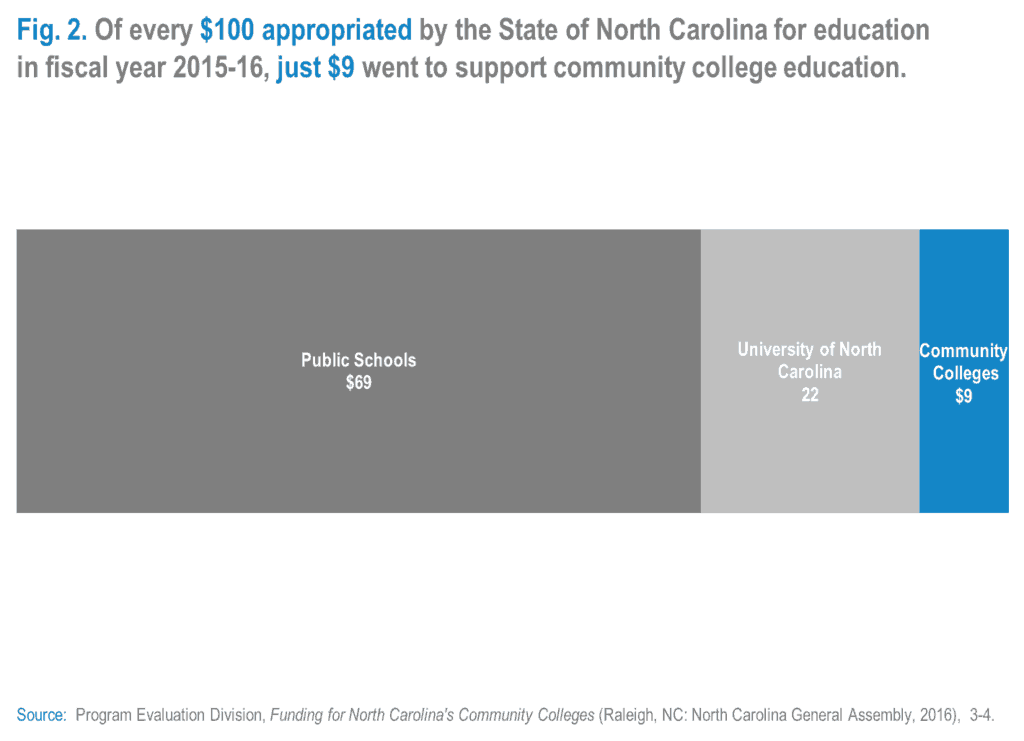

Past research from EdNC found that, in recent years, the NCCCS has received roughly $9 of every $100 appropriated for education, the UNC System $22 of every $100, and the public schools $69 of every $100.2 On a relative basis, the NCCCS receives the least amount of support, the University of North Carolina System, the most.3

The overwhelming majority of the money appropriated to the NCCCS supports academic instruction, primarily faculty salaries. Tracing the flow of money from the state treasury to the paychecks of instructors requires a familiarity with the faculty employment model, the state funding formula, and the interplay between the compensation policies set by the State Board and the administrative practices of local colleges.

State-funded employees of local colleges, not state employees

Although the State of North Carolina funds the salaries of community college instructors, it does not directly employ those educators who instead are employees of the individual colleges where they teach and so are not subject to the North Carolina Human Resources Act.4 The State Board has the authority to set certain broad parameters related to employment relationships—such as establishing salary standards and scales, administering state appropriations, and requiring that hiring practices satisfy the faculty accreditation requirements of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Otherwise, local colleges have broad latitude when it comes to the management of their faculty corps.5

“We have 58 different personnel plans and pay plans, and that’s the beauty and curse of having the level of autonomy we’re blessed to have,” remarked Dale McInnis, president of Richmond Community College in Hamlet.6 “There’s no state-level salary plan for faculty. There are minimums that are defined annually, and where those floors are [is] based on the academic attainment level of the faculty.”

McInnis’ comments touch on a common misconception about community colleges: that instructors are paid on graduated schedules like those used for public school teachers. A teacher in a North Carolina public school with a master’s degree and 10 years of experience, for instance, currently receives a state-funded base salary of $49,500 per year regardless of where the teacher works; assuming no changes to the schedule, that teacher would receive an automatic raise of $1,100 the next year.7 A full-time curriculum instructor at a two-year college with a master’s degree, in contrast, is only guaranteed a minimum salary of $42,382.8

Calculating the state’s contribution

The General Assembly long has distributed funding to community colleges primarily on the basis of student enrollment. Consider how, in fiscal year 2016-17, some 83% of state funding was distributed based on an enrollment formula, with the remainder coming from base allotments (15%) and performance awards (2%).9

Full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment is the core unit used to determine how much formula funding a college receives. For curriculum programs, a college earns one FTE for every 512 hours of class or laboratory hours scheduled in a year, and continuing education programs generate one FTE for every 688 hours of scheduled course time.10

Colleges receive budget FTE based on the higher of the FTE earned in a given year or the average of the actual FTE earned over the past two years (a three-year average was used until 2013).11 This helps to stabilize funding against sudden fluctuations caused by enrollment changes stemming from factors beyond a college’s control, such as shifts in the business cycle.

Each budget FTE carries a specific allotment, or dollar value, that ranges from $2,143 to $4,401 in fiscal year 2019-20.12 In 2011, the General Assembly implemented a tiered funding model under which the value of an FTE varies depending on which of four categories it falls under. The idea is to provide more funding to programs that are more costly to operate, such as health care and technical programs, or that support industry and award in-demand credentials.13

“I’ve been in the system long enough where I remember when that distinction wasn’t made, so you got the same for doing nursing as you did for doing English,” reflected Pamela Senegal, president of Piedmont Community College.14 “While those are equally valuable, the reality is that it costs me more to run a nursing class. My ratio of students in the nursing class has to be lower.”

To illustrate these dynamics, consider how formula funding for PCC’s curriculum programs was determined for fiscal year 2019-20. The total budgeted FTE was 962, with 203 FTEs in Tier 1A programs (value: $4,401), 258 in Tier 1B programs ($3,893), and 501 in Tier 2 programs (value: $3,385).15 The total amount generated by the formula was $3.6 million, which, when added to a base allotment of $0.4 million given to every college, yielded $4 million in state funding. Those funds are to support “instructional salaries, fringe benefits, and other costs, such as supplies, materials, and faculty travel” related to curriculum programs.16

Prior research by EdNC described the adoption of tiered funding as a positive step toward addressing a historic inability of North Carolina’s community colleges to support high-cost programs. Yet the study also found that “it remains unclear if the values associated with different FTE categories actually capture true differences in costs and are sustainable.”17

“I don’t know if the difference between the [Tier] 1A and the [Tier] 3 are enough to give me flexibility to put those dollars in a significant way towards some of my high-demand salary faculty positions,” added Senegal.18 “I think it is a step in the right direction, but I think we have to continue to push that those formulas be at a higher dollar value for it to really have the impact that it was intended to do. It’s a great start.”

The interplay of state policies and local administration

The State Board has the statutory responsibility for “providing, from sources available to the State Board, funds to meet the financial needs of institutions, as determined by policies and regulations of the State Board.”19 Within those broad parameters, individual colleges are free to allocate their resources as they deem best.

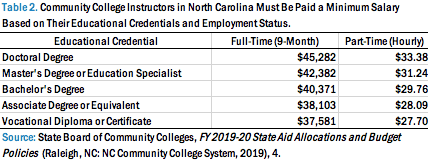

As noted earlier, there is no uniform set of pay schedules for community college instructors. The State Board instead establishes minimum salaries for full-time and part-time curriculum instructors. The minimums vary based on an instructor’s educational credentials. For full-time employees, the salary floors range from $37,581 for a holder of a vocational credential to $45,282 for a holder of a doctoral degree (Table 2).20

Part-time instructors are paid an hourly rate equal to the minimum salary for their education credential divided by 1,560 hours, which is equal to 75% of the 2,080 hours in a standard work year. To that amount, another 15% is added to compensate an instructor for work outside of direct class time, such as grading. On an hourly basis, the salary floors range from $27.70 for a holder of a vocational credential to $33.38 for a holder of a doctoral degree.21

“It [the State Board] does not tell us we have to pay this person with this many years and these credentials this amount of money,” said President McInnis of Richmond Community College.22 “It’s market driven. I would say that even more so than the public schools or even the universities, our faculty and staff salary process and arrangement is entirely driven by market factors.”

When asked to explain how his management team decides on the salaries offered to different instructors, McInnis offered that “supply when you advertise for a professor, the number of applicants that are qualified, is going to drive salary. And that’s where the market comes into play. A starting salary for an English, math, history, or sociology professor is usually going to be much different than that for a nursing professor, an engineering professor, or another person who might have marketable private-sector skillsets.”23

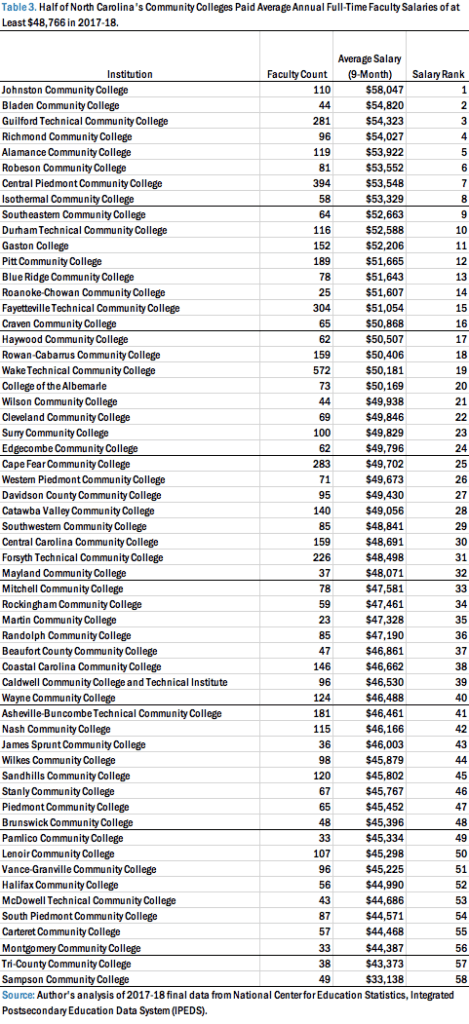

Local discretion in setting pay in response to area conditions is reflected in the broad range of annual average salaries paid at the institutional level. In 2017-18, average annual full-time faculty salaries ranged from $58,047 at Johnston Community College in Smithfield to $33,138 at Sampson Community College in Clinton (Table 3).24 Half of all colleges paid at least $48,766, half less than that.

And there are no clear geographic or size patterns to the data. At $54,027, Richmond Community College in rural Hamlet posted the third-highest average annual full-time faculty salary, while metropolitan Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College ranked 41st, with an average annual pay figure of $46,461.