When I was a little boy, I loved to read Fire! Fire!, a Gail Gibbons book about firefighters who responded to emergencies in the city, country, forest, and water. I made my parents read it to me every night for months. I am sure they quickly tired of it, but those early moments of burying my nose in a page were transformative. I moved on to the Hardy Boys series, and, eventually to classics like The Old Man and the Sea. The wooden bookshelf in my bedroom was so crammed with titles that the shelves creaked.

I grew up in a household that embraced books. My grandparents, who lived with us, were avid readers of poetry and prose. Importantly, our family was privileged to be able to afford new books, to have reliable transportation to a nearby public library, and to have the stability that enabled the grownups to be home at night to read to me when I was young.

In reporting about Read Charlotte—the public-private partnership designed to double Mecklenburg County’s third grade reading proficiency by 2025—I was struck by this county’s “book desert.”

About 40 percent of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools fourth graders say they don’t have more than one shelf of books—on any subject, for any age—at home. That statistic resonated, and I kept returning to it throughout my work on this topic.

Overwhelming research connects early childhood literacy to future success. In Mecklenburg County, for example, 96 percent of students who are proficient readers by the third grade will go on to graduate high school on time. Access to books, especially at home, is vital to building language, literacy, and comprehension skills that lead to prosperity later in life.

There’s an economic incentive here, too, for individuals and communities.

A little more than halfway through Read Charlotte’s 100 Day Challenge this spring, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Opportunity Task Force released a much-anticipated report on improving economic mobility here. The report, which leaders unveiled to a standing-room-only crowd in late March, included 91 recommendations. A central tenet was the access to quality early care and education.

“The Task Force strongly supports the work of Read Charlotte and see it as an important intervention for economic opportunity,” the report states. Members believe there’s a correlation between literacy and mobility. “Work remains to be done for all children and youth,” the Task Force says, “regardless of geography, race, gender, and ethnicity.”

The Opportunity Task Force, created after a study ranked Charlotte last among 50 U.S. cities in terms of economic mobility, recommended providing “expanded support of Read Charlotte and (ensuring) necessary resources are available to implement identified strategies.”

Read Charlotte’s work is still in its early stages and hinges on the cooperation of a wide network of agencies and individuals whose efforts have historically existed in silos. Some of what Read Charlotte wants to do—systems change, for example—seems daunting.

But some of its interventions are delightfully simple.

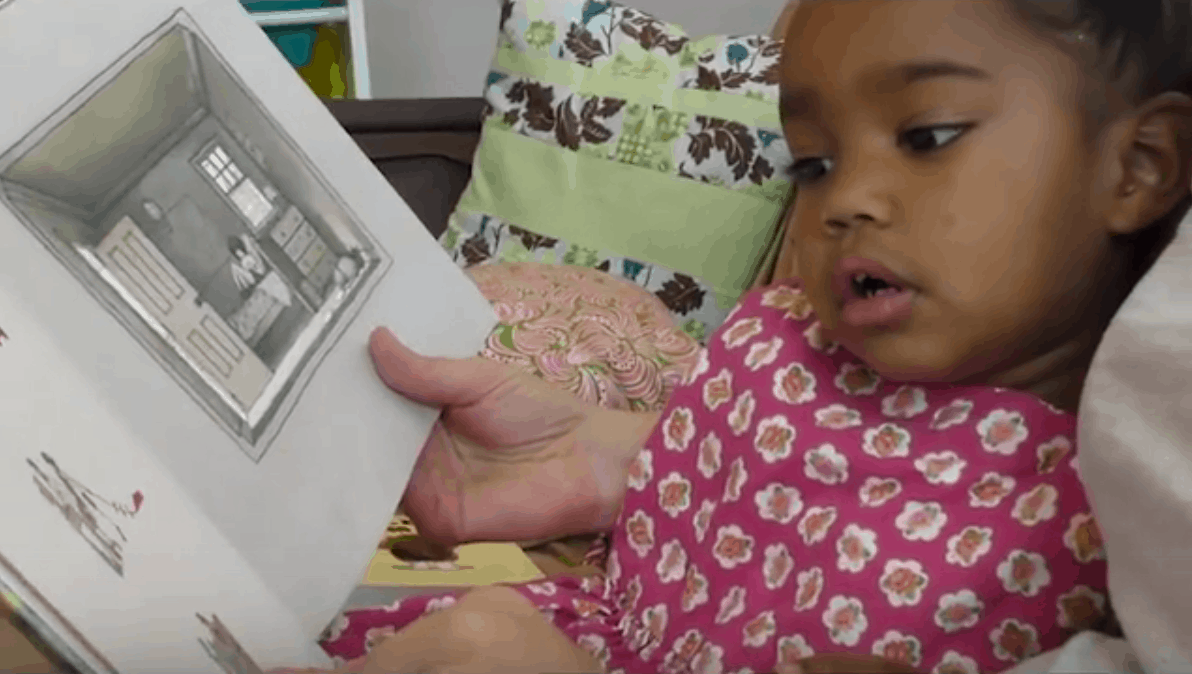

Last year, the organization gave out 30,000 books, one to each pre-kindergarten through third grade student in CMS’ Title I schools. For free. A Charlotte Observer story about the initiative highlighted a little girl who read the same book every night before bed—because it was the only one she owned.

I thought back to my crammed-full childhood bookshelf, the trips to the library, the nights with Fire! Fire!

If an initiative can put books in the hands of kids who otherwise wouldn’t have them, what’s there to lose? And, since it might do so much more, why wouldn’t we think about how to scale the initiative in communities across North Carolina?