Julie Smith, a licensed counselor for Child First, an intensive home visiting program that provides mental health support to young children in eastern North Carolina, calls the COVID-19 pandemic “a recipe for disaster” for her clients.

Smith says the closure of the services families rely on — as well as stress from financial hardship and social isolation — has left children and their caregivers in unstable and unsafe conditions.

“I say a lot of prayers at night before I go to bed,” Smith said. “I hope and pray my clients I’m most concerned about are safe in their home situations, and they’re getting what they need, and they’re not being neglected.”

Smith is one of hundreds of home visitors across the state who have served as windows to the outside world and links to much-needed resources during months of stay-at-home procedures.

Experts on children’s health have expressed concerns about increased risks of child abuse and neglect and other emotional effects on young children stuck at home. Across North Carolina, domestic violence reports have increased, and shelters have prepared for increased need.

Many home visiting programs, like Smith’s, focus on children who are at risk of these traumas. Paul Lanier, associate director of the Jordan Institute for Families at UNC-Chapel Hill’s school of social work, said home visiting programs of all sorts are still proving to be critical for the children they reach. But that reach is limited.

“This is a lifeline for a lot of families, and we need more service availability,” Lanier said. Research has shown that home visiting programs can produce positive academic, health, and developmental benefits for children, yet a 2018 study, led by Lanier, estimated that North Carolina’s programs meet only 1% of families across the state. Generally, rural areas had the largest gaps in program reach.

With focuses from school readiness to child abuse prevention, these programs work to strengthen relationships between young children and their caregivers.

“My goal is to connect with families — children and their caregivers — and through that connection, you’re supporting their connection,” Smith said. “You want them to connect to each other.”

A tricky virtual transition

During the pandemic, programs have adapted while a critical aspect of their work has been eliminated: in-person observation of children and parents in their everyday environments.

Sometimes, that has proven difficult.

“I need to see how Mom responds to Tommy when Tommy throws the ball at the dog and hits the dog in the head,” Smith said. “Does Mommy scream? What does Mommy do? Does Mommy throw the ball at Tommy? You have to be there to be able to see that.”

Other visitors and program coordinators say they have seen more engagement and open communication from virtual meetings, texts, and phone calls with parents. Nickey Stamey, director of Blue Ridge Healthy Families in western North Carolina, said she thinks the collective struggle of communities has made the families she serves more comfortable with being honest about their own challenges.

“The crisis has normalized the need for help,” Stamey said in an EdNC interview in April.

Lanier, who is now working with a cross-sector team to push for more awareness of and support for home visiting, said that what has remained throughout the pandemic and connects the network of programs across the state is the trusting and supportive relationship between families and home visitors. Before teaching parents specific skills, these programs often are making sure families have their most basic needs met, like housing and food.

“They try to brand themselves to hit these big ticket outcomes like reading or maternal depression, but they’re also all really doing some basic case management functions and serving as, in some cases, the only social support that these new families have,” he said.

During a pandemic, those needs are great. For Smith in Martin County, that means being the only service reaching a homeless family with a severely autistic child.

“How can you help Mom connect to Bobby if she’s wondering where she’s going to sleep tonight?” Smith said.

At ParentChild+ in Charlotte, home visitors at one site are technically employees of Inlivian, the housing authority in the neighborhood, and connect families with housing and employment resources before working on academic skills. During the pandemic, home visitors have curated emergency resources and offered to collect food for families.

In Yancey, Mitchell, and Avery counties, Blue Ridge Healthy Families staff delivered cleaning supplies and hard-to-find products in laundry baskets to families with young children. When asked about the role of the program during the pandemic, Stamey said: “Home visiting is filling a huge gap for families. A bridge, really.”

For Book Babies, in Durham and Winston-Salem, home visitors are gauging families’ technology needs and helping parents get access to at-home learning resources.

“Home visiting and parent education is a necessity to meet the increased risk to child welfare,” said Meytal Barak, Book Babies team leader and family partnerships manager. “Each program has a different scope, but we are a connector to resources.”

A push for coordination

The 2018 study, funded by The ChildTrust Foundation, The Duke Endowment, the John Rex Endowment, and the Winer Family Foundation, calls for more investment and infrastructure in the state’s home visiting system. The “funders’ note” opening the report points out the programs’ limited resources and coordination:

Home visiting services have been woven into our state landscape since 1991, funded by a range of federal, state and philanthropic support. North Carolina is fortunate to offer several nationally recognized home visiting models in some communities, but most of the existing programs operate in funding and service silos and are not integrated into a larger early childhood system. This lack of coordination makes it difficult, if not impossible, to ensure that home visiting resources are equitably and sufficiently available throughout the state.

Since the report’s release, Lanier has been part of a group working to communicate the value of home visiting, but said not much has changed in the last couple of years as far as reach or funding. One of the report’s recommendations calls for “a statewide home visiting strategic vision and action plan that is completely integrated with a comprehensive system of care.” That plan is starting to be put into action, he said.

“Unfortunately, the reality is it’s such a small penetration rate,” he said.

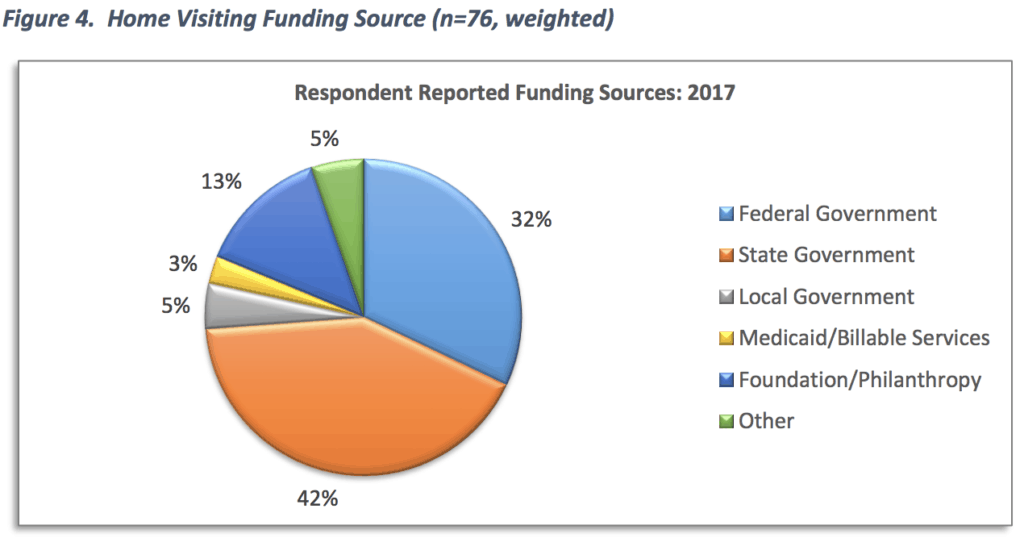

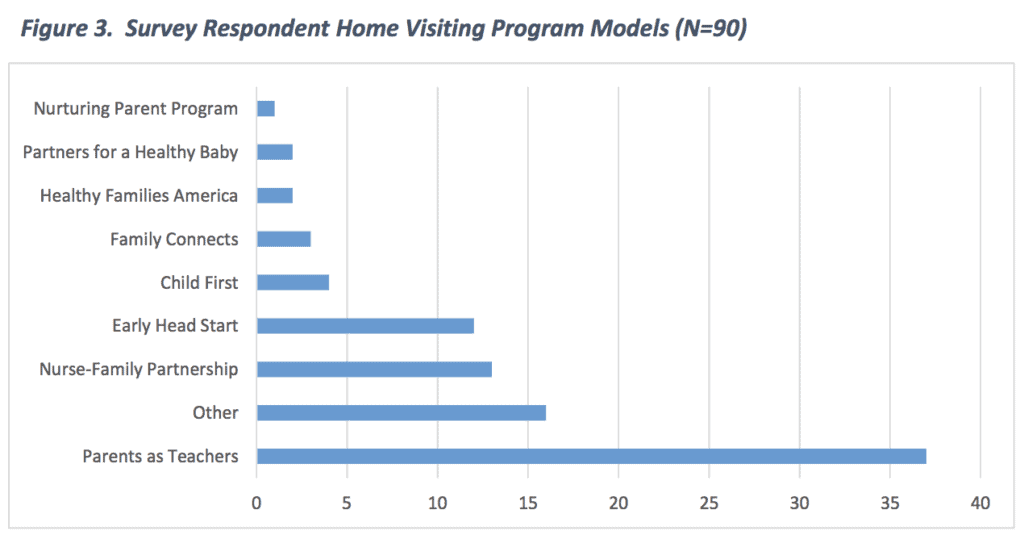

Lanier said 20 counties have no home visiting programs at all. Programs’ funding comes from a variety of state, federal, local, and private streams. The following graphics break down the funding sources and models of the 93 programs that responded to the 2018 study.

Lanier said most people in American culture still think of those early years of children’s lives as ones that parents should figure out on their own, but that isn’t the case everywhere. “Our culture is totally backwards here,” he said.

That’s a norm he hopes will change.

“Parenting is hard in general, especially with young kids,” Lanier said. “Some of the things are instinctual, like a mother’s love for a baby. Most of the time, hormones kick in and it’s just instinctual. A lot of things about child rearing are totally skills-based, like changing a diaper, for example. There’s not some hormone that kicks in so you know how to change a diaper; someone has to show you how to do that. There’s a lot of things that require person-to-person transmission of information. … These programs can often fill that huge need or that gap around skills.”

As services reopen and individuals return to work, Smith said the effects of the pandemic will persist.

“I think when kids are allowed to have an outlet, to go back to school, find comfort in teachers and other professionals, we’re going to learn a whole lot of stuff we don’t want to know, sadly,” she said.

Lanier echoed that sentiment, and said that’s why supports for families like home visiting will be even more crucial moving forward.

“We need to invest more in it,” he said. “Hopefully, the positive stories kind of outweigh the alarming things we’re going to hear probably.”

Editor’s Note: The ChildTrust Foundation and The Duke Endowment support the work of EducationNC.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled the name of a funder of the 2018 home visiting study, the John Rex Endowment.