A team of education leaders, charged with recommending improvements to reading instruction in classrooms across North Carolina, is refining its final proposals.

The State Board of Education’s literacy task force has taken on big questions in recent months: How can reading instruction improve? How can teachers be better prepared in college? How can current teachers learn more effective strategies?

North Carolina students’ reading scores have not improved much in recent years despite the state’s Read to Achieve law, which aimed $150 million in funding toward increasing reading proficiency, but with no impact. In 2018-19, 57.3% of third-graders were reading on grade level.

The lack of progress has led to heightened attention from state leaders — from legislators to State Board members to philanthropists. The Pre-K-12 Literacy Instruction and Teacher Preparation Task Force started meeting at the end of last year, comprising experts from educators to leaders of education preparation programs to researchers.

The group will present recommendations to the State Board in June on how teacher preparation, professional development, and instructional materials “can change to reflect effective, evidence-based reading instruction,” according to an April presentation from task force chair Ann Clark, who is a former Charlotte-Mecklenburg superintendent and a Belk Foundation board member.

Clark said on a call with members Monday that state legislators are tuned into the group’s work as they consider changes to Read to Achieve.

The virtual meeting Monday allowed several members to review and discuss the task force’s draft recommendations, from placing literacy coaches in all elementary schools to helping districts pick effective curricula.

The group will continue to work out its recommendations on a call with the remaining members next Monday, and will meet as a full body to approve the final recommendations before the end of May.

Find the full draft recommendations embedded at the bottom of this article.

Professional development

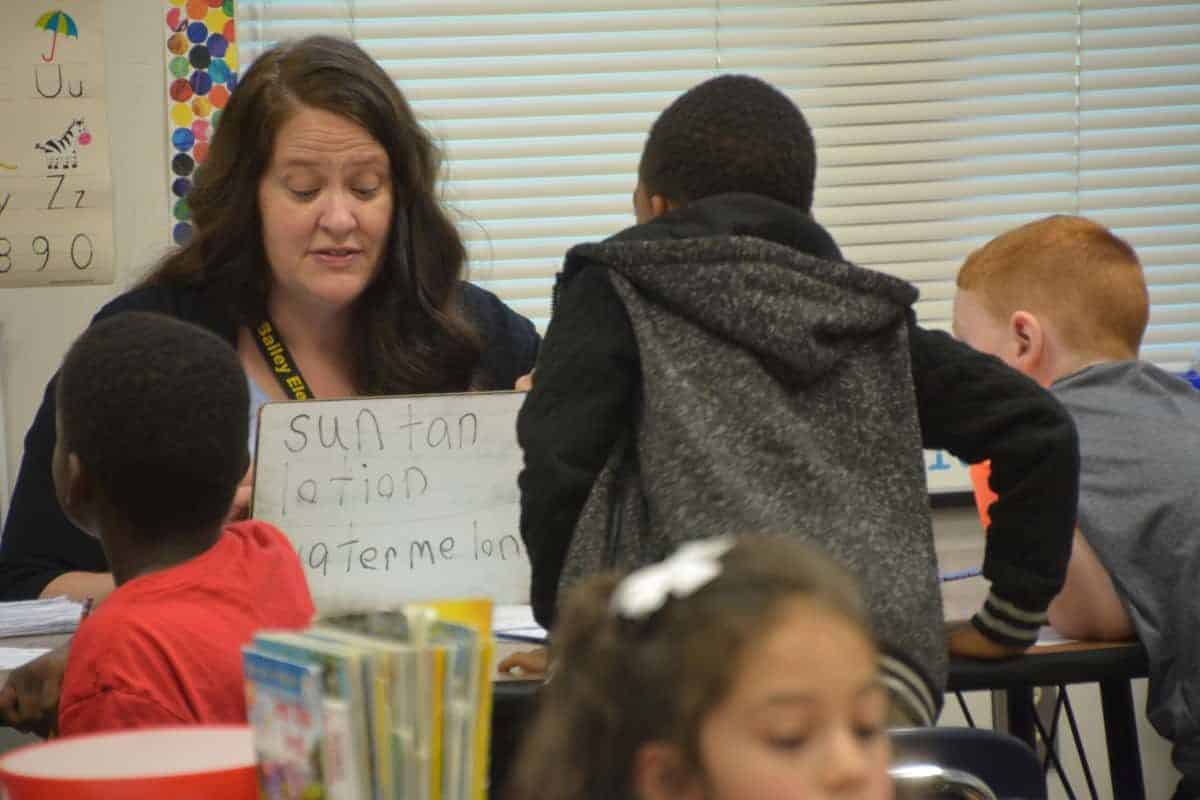

The task force is thinking of ways to support and improve the work of the thousands of elementary school teachers who are instructing students to read across the state.

The group’s draft recommendations include funding for professional development for elementary teachers, administrators, and instructional coaches that is based on current scientific research on reading instruction.

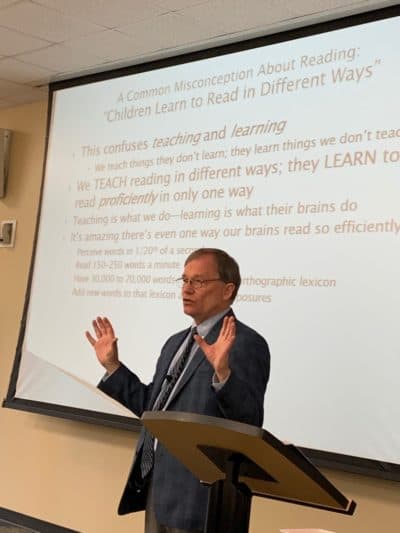

Advocates pushing for change in reading instruction in North Carolina and beyond commonly refer to this body of research as “the science of reading.” There is not one specific approach or program tied to this phrase, and the research is evolving on the complex processes of brain development that facilitate reading. That has left the task force questioning exactly what words to use in its policy suggestions. More consistency will come, members said Monday, as the recommendations are finalized.

The group is preliminarily suggesting placing two literacy coaches to provide hands-on support to teachers in each elementary school throughout the state — one for teachers from pre-K to second grade, and one for teachers from third to fifth grades. The ratio of the number of coaches to school size is still being worked through.

“In an elementary school with 1,000 students, two coaches will not sufficiently allow the support that we know would be required,” Clark said.

Tara Galloway, director of K-3 literacy at the Department of Public Instruction, suggested Monday specifying the type of training those coaches should receive.

The group’s draft recommendations also include a micro-credentialing process for early literacy training, as well as professional development requirements in reading instruction for both elementary teachers and principals upon renewing their licenses. The professional development group is also looking at increased compensation for individuals with advanced degrees related to literacy.

Members are still deciding exactly how educators and policymakers would know whether these initiatives are working — and what “working” means.

“Whether or not it’s professional development or whatever we would be measuring, growth always comes to mind for me when we’re talking about measuring effectiveness,” said LaTanya Pattillo, task force member and teacher advisor to Gov. Roy Cooper.

Instructional materials

So what curricula and materials should teachers use to teach children to read?

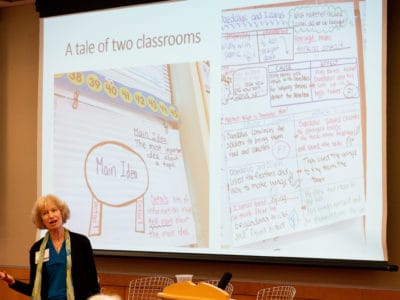

One of the group’s draft recommendations suggests creating criteria for materials “aligned to the science of reading” as well as a panel of experts to decide which curricula districts could choose from.

“Many districts don’t have the expertise or the capacity to vet all of these materials, and are there recommended materials that meet the science of reading … that there would be a list of?” said Beth Folger, a task force member and superintendent of Onslow County Schools, as she presented the group’s draft recommendations Monday.

But some members expressed concerns that a specific list of curricula may get the state in the middle of “vendor wars,” and that a list wouldn’t allow districts to choose the materials best suited for their needs, factoring in costs and specific district initiatives.

“I’m not as comfortable with the idea of a list because it begs the question, how many? And do you have to use what’s on the list? I feel like that’s a little restrictive,” said Vickie Sutton, a task force member and Greene County’s K-5 literacy coordinator.

Members suggested Monday that a rubric might be better.

Either way, the group’s draft recommendations include ensuring that all students have access to curricula that are high-quality and aligned to scientific research on reading. The group initially suggests creating statewide materials to outline what that research is, providing professional development aligned to the district’s specific curriculum, and creating an implementation rubric for teachers and school leaders to measure the roll-out of the curriculum.

The draft recommendations say that all statewide materials and assessments should be aligned to the current research on reading science, as well as funding and implementing diagnostic assessments for the reading progress of fourth- and fifth-graders.

Currently, the state uses a diagnostic literacy assessment for only grades K-3, a requirement of Read to Achieve. The purpose of these assessments is for teachers to be able to adjust their instructional strategies based on where students need help.

“We have fourth- and fifth-grade students who we also need assistance in identifying their areas of need,” Folger said.

Teacher preparation/licensure

The group is also tackling teacher preparation to ensure that teachers entering the classroom have the experiences and knowledge to be effective teachers of reading.

Much of the work of this subcommittee is based on a different set of recommendations from a group convened by the University of North Carolina system that similarly studied preparation programs’ approaches to literacy instruction.

The task force’s draft recommendations focus on aligning the coursework, clinical experiences, assessment, and overall understanding of future elementary teachers with the strategies that reading science supports.

Once new teachers enter the classroom, the draft recommendations also suggest, schools need to be ready to help them succeed, suggesting professional learning for principals and mentors who help teachers as they start teaching reading.

Another draft recommendation says principal preparation programs should include “substantive coursework” based on current research in reading science. Clark said the idea is for school leaders to be able to support effective teaching.

“I think we’re thinking in terms of both the types of professional development they would offer and their ability to make sure that there’s alignment there, as well as their ability to go into the classroom and observe a reading lesson and give substantive feedback,” Clark said.

One draft recommendation calls for a panel of experts to create a statewide strategy on aligning the preparation of pre-service teachers and the expectations and professional development of the same people once they arrive in the classroom. Others call for a statewide strategy on elementary teacher recruitment and diversification and a way to differentiate between novice and master teachers of reading as they begin their careers.

The group also suggests establishing pay incentives for teachers, school leaders, and coaches who earn master’s degrees or special certifications in reading instruction.

Find the full draft recommendations below.