Courtney Patterson has been working overtime, alongside grassroots community organizers and leaders. Hurricane Florence made landfall more than three months ago, and while much of Southeastern North Carolina is in the midst of long-term recovery, the communities he visits and serves seem to be struggling more.

“In Robeson County, there are people who are actually living in their cars,” said Patterson, the fourth vice president of North Carolina NAACP. “They go in their house to take a shower or cook some food, and then they go to their cars.”

In Pender County, he’s seen elderly people living in homes without electricity or heat. Some are using kerosene heaters, which raises other risks of catastrophe. In New Bern and Wilmington, he’s seen people living in condemned properties which have not been gutted, mitigated, or remediated for mold.

“These are the kinds of things people are facing,” Patterson said. “And they cannot identify help.”

To hear him tell it, he could be speaking of any number of communities. But in many communities, he says these issues are present but known – and because they are known, help is on the way. In communities that are predominantly African American or poverty-stricken, the struggle remains hidden.

“When white people get a cold, black people get the flu,” he says, repeating an old saying in many African American communities. By this, he means that while Florence hit many communities hard, the hit to rural, predominantly African American or impoverished communities is felt harder because of pre-existing conditions such as limited resources and his belief that those who have help to give simply don’t know where to find those who need it most.

“It is clear to see that communities who are most impacted by this destruction are disproportionately low-income communities and communities of color who are already burdened by decades of pollution,” says La’Meshia Whittington Kaminski, a community organizer working with Patterson. “So we are here to say that Hurricane Florence, and Matthew before it, are not just natural disasters. They are the logical outcome of a society that believes certain people and lands are expendable. And this is unacceptable.”

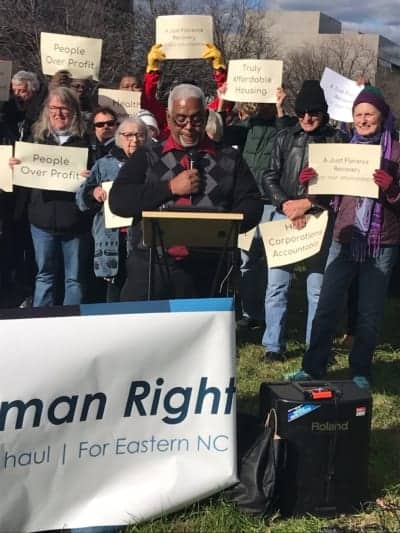

A Just Florence Recovery effort

Patterson is on the board for Blueprint NC, a network of non-profits working on various issues along racial lines to advance for equity and social justice. Blueprint was primarily in the Triangle area before expanding to Eastern North Carolina in the weeks prior to Hurricane Florence making landfall.

One of Blueprint’s major efforts is to register voters in low-income and black communities, and they were making site visits just prior to Florence’s arrival. As a result, they got to know the communities and the people before the storm made communication and outreach difficult. When Florence hit, the Blueprint organizers on the ground heard and saw first-hand the needs of the communities they were visiting.

They formed an ad hoc group, and repurposed a similar initiative’s name from after Hurricane Harvey, to form the Just Florence Recovery effort – which aims to bridge the gap between recovery relief for low-income, black communities and the rest of impacted North Carolina. Their goal is to offer help and fight for a result that leaves these communities in a better position to withstand future storms.

“A lot of times, folks don’t know where they are,” Patterson said. “I’m very reluctant to say that we have communities or cities or towns that are racist and don’t go out and help folks when they know they need help. I wouldn’t think that would be the case. It’s more so just because of the separation between where they live as opposed to where other folks live, they just don’t know.”

Blueprint’s first move after the storm was to take $1,000 from each of eight groups they had funded in Eastern North Carolina and use that money to provide immediate relief.

As they strategized what to do next, volunteers began to find them. One woman called on the Monday after the storm wondering if the group needed an airplane. With that, and hundreds of volunteer pilots, they were able to fly supplies into New Bern, Wilmington, Lumberton, and other rural areas not reachable by cars.

All of the communities they served, Patterson said, were overlooked communities.

“Our state government was not necessarily in tune with what was needed in order to have a just Florence recovery,” he said, noting that Blueprint’s efforts were successful primarily because “we were already there, we knew where they were.”

Because Blueprint did, they were able to distribute 350,000 pounds of supplies – over 100 truckloads – in the week following the storm.

“In many cases, these were communities that would be last to get served,” Patterson said. “So these were people who were able to get served this time. We think that when history reports on this, that this work that was done by many people, many volunteers, many groups who put in the effort for all of this, history will prove that lives were saved because of this.”

The group was able to provide discretionary funds, which were put to vital uses like a Craven County woman who was on oxygen but had no electricity. Just Florence Recovery was able to get her a generator. They also worked with the Cajun Navy, an informal group of private boat owners who perform rescues after disasters.

“There were a lot of things we were able to do for people who maybe wouldn’t have otherwise got help early,” Patterson said. “So thank God there were people with Just Florence Recovery who were able to go out and to do that.”

Pre-existing situations compound recovery

After providing help in the immediate aftermath, the group now focuses on how money is allocated for survivors and how communities are rebuilt. The communities Patterson works with, he says, don’t have many options outside of the government.

“You’re dealing with some people who don’t have money,” Patterson said. “They don’t have insurance and they don’t have credit. So they’re without help there. I hear from the political people that there’s dollars out there to help those people, but they don’t know about them, and I don’t know about them.”

Adrienne Kennedy is a disaster relief activist. She was the vice chair of a Robeson County Long-Term Disaster Relief Council after Hurricane Matthew, and she has personally experienced displacement during both Matthew and Florence.

The people she works with, predominantly African American, are frustrated with the level of help from the government. She has helped many of her neighbors, family members, and friends work with FEMA. Because this constituency is largely comprised of renters rather than home owners, however, she says FEMA housing assistance is of little to no help.

“They give up,” Kennedy said of the people she works with. “They don’t get any help and they just take the loss. It’s not fair. It’s not right.”

The result is that people pick up and leave their communities. They do so for lack of funding, lack of remaining housing after the storm, fear of whether future housing built — if it remains affordable — will withstand the next storm.

“It’s not fair housing,” Kennedy said. “They can build houses and elevate houses that can get through the storm, but in these communities they are not doing that.”

Wondering if help is intended

The view from Front Street in New Bern, looking out over the Trent River, is picturesque. Behind it sits Tryon Palace, the opulent colonial mansion which housed the British government during pre-revolutionary times.

Along the side street north of the river, off Broad and Pollock, beautiful homes show damage from Hurricane Florence, which was particularly rough on Craven County. But already, some homes have been repaired, others renovated, and elsewhere sitting construction equipment evidences recovery on its way.

But tucked just a few streets to the east, at the lip of Front Street and just yards before the majestic marina view, stands Trent Court apartments and its 218 units of affordable housing offered through the public housing authority. It’s prime real estate and has been the subject of controversy where local government has proposed moving the affordable housing so that it is outside the 100-year floodplain, relocating its residents, and replacing it with a new, mixed-income community.

Some 140 of the 218 units were damaged by Hurricane Florence. Many residents evacuated, or were rescued and taken, to a shelter in nearby Trent Park. Many are still there. Others are roughing it out in their Trent Court apartment, where mold and infrastructure make the conditions dangerous, but these residents have nowhere else to go.

Patterson and Kennedy are familiar with the situation.

“They don’t intend to put public housing back in that area. They intend to make sure that people can go in there and investors can invest in those communities. Develop those properties. These are properties that are very valuable these days and you’ve got this marina that just sits right in there – they would love to expand all of that.”

“With the rising prices and that kind of thing — just push these people aside. They’re not important, they’re not relevant, let’s just push them aside. That’s sort of the attitude.”

Kennedy said the people living in these types of communities are susceptible to offers of little sums of money for relocation after the storm. After all, she says, they have no other place to go, their credit makes it difficult for them to find other places to rent, and they often have had interruptions to their desperately needed hours at work in the wake of the storm.

“It’s systemic,” Kennedy said. “It’s the same story that we’ve seen before.”

The real estate issue is a sensitive one for Just Florence Recovery representatives, who believe there is a pattern of placing low-income individuals in land that is not only prone to flooding, but also in the path of man-made waste that makes the impact of the storm — and recovery afterward — that much harder.

“It was also a disaster that was created by things like Gen X, things like coal ash, things like hog lagoons and other things that could have been taken care of long before the storm,” Patterson said. “And we feel like those people who contributed to that should have part of the responsibility for making people whole again.”

The initiative is a young one, having formed in North Carolina only months ago. But they have their sights set high. They say their demands are few: They want a transparent recovery effort, and they want the government’s attention and help — both to direct money to those who are suffering most and to ensure that, where government allocations cannot meet the needs, corporate polluters are held responsible for making up the shortfall.

“Our legislators in North Carolina have been more focused on suppressing voters through things like Voter ID than they have been concerned with their constituency suffering through the hurricane and trying to get their lives back together,” Patterson said. “Our message is simple. We want a just recovery.”