Student assessment has been the topic of many initiatives and conversations in education policy as of late. There are multiple bills introduced this legislative session that would tweak or eliminate testing requirements. Superintendent of Public Instruction Mark Johnson has put testing reduction as one of his department’s priorities this year, and the State Board of Education passed a policy at its last meeting that eliminates certain elementary tests on social studies and science.

This week, the Governor’s Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education looked at where the state is with testing and accountability, what a balanced assessment system could look like, and how data the state collects translates to supporting schools. The commission is addressing how the state can meet its constitutional mandate to provide equal educational opportunity to every child. Along with a report from outside consultant WestEd, the commission will give its final findings to the State Supreme Court as part of the decades-long Leandro lawsuit. The lawsuit started when several low-wealth counties sued the state, saying their students were not receiving the same quality of education as wealthier districts.

Commission members Thursday heard from the state’s accountability and district support teams, outside assessment and testing experts, a literacy director for Wake County Public Schools, and an expert in the history of turning around low-performing schools. Members expressed concerns that testing takes up too much instructional time and does little to improve teaching and learning. Another repeated sentiment was that the assessment system is confused about the purpose of the data it collects: to drive instruction or to hold the school system accountable.

Nick Sojka, a commission member and school board attorney for Cumberland County Schools, emphasized a point many presenters and members made throughout the meeting on assessment — from the classroom to the state level — that more resources are needed when more expectations are set.

“What I hear over and over and over again is that we as a state and probably as a broader society have just piled on tremendous pressures on everybody involved in public education from the littlest pre-K student on up to the superintendents and the school board members, but I just don’t think the support’s kept up,” said Sojka.

The newest federal education legislation, the Every Student Succeeds Act, requires the state to test students in reading and math in grades 3-8 each year and once in high school. The law requires the state to test students in science once in grades 3-5, once in grades 6-8, and once in grades 10-12. In North Carolina, End of Grade (EOG) tests are administered in grades 3-8, and End of Course (EOC) tests are administered in particular classes in high school. NC Final Exams are used in certain courses that lack EOGs or EOCs across elementary, middle, and high school to provide teacher effectiveness data to the state.

For math in grades 4-8 and reading in grades 3-8, NC Check-Ins are another assessment some teachers use as interim benchmarks during the year. These are voluntary and meant to be diagnostic, though the state testing team said there is a chance these could shift towards being more high-stakes.

“If it becomes more for accountability purposes, they would not be able to get the item-level data that they’re used to getting from the NC Check-Ins,” said Kristen Maxey-Moore, section chief of test development at the Department of Public Instruction (DPI).

LaTeesa Allen, DPI’s interim deputy state superintendent of innovation and the superintendent of the Innovative School District (ISD), explained different reasons for those tests: admission to postsecondary education, promotion from one grade to another, accountability, evaluation of teachers and programs, to assess what students need, and to assess mental ability or IQ. Allen said tests are made to reflect the standards the State Board of Education adopts.

“So when new content standards are adopted, we do revise the tests to make sure that that alignment continues across time,” Allen said. “What’s really important to note is that our North Carolina teachers are very instrumental, they’re very engaged, in writing and reviewing these items.”

Mark Jewell, commission member and president of the North Carolina Association of Educators, said assessments are inevitable and were originally developed by teachers and used for diagnostic purposes for decades. In recent years, however, Jewell said instruction is supporting tests rather than the other way around.

“It’s the amount of pressure that’s put on the assessments and the punitiveness that has created so much conflict in our classrooms,” he said. “… The curriculum is actually becoming the testing instrument.”

Maxey-Moore agreed that formative assessments done in the classroom for instructional purposes are part of moving towards a balanced assessment system.

In kindergarten to third grade, there are literacy assessments given three times each year using a platform called mClass that measures two components of student literacy: DIBELS (dynamic indicators of basic early literacy skills) and TRC (text reading comprehension). This assessment is part of the state’s Read to Achieve program, meant to approve third-grade reading proficiency.

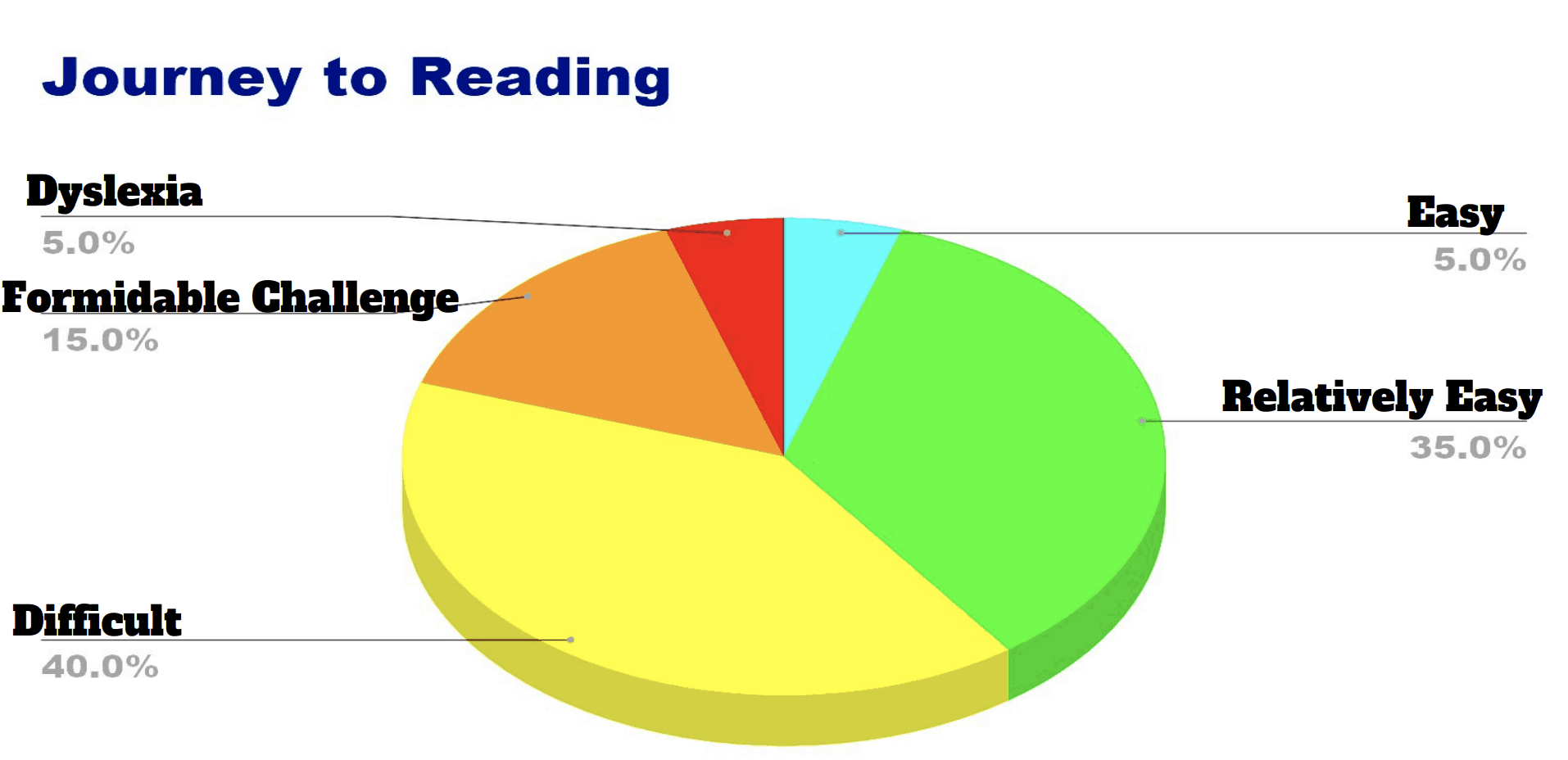

Sherri Miller, Wake County Public Schools’ director of literacy, explained these literacy assessments and how teachers use them to determine how best to teach different kids to read. Miller explained that around 60% of children have trouble with reading, from finding it difficult to having a serious language processing issue like dyslexia. Those children, Miller said, require specific targeted strategies and highly-skilled literacy teachers who can see what the barriers to learning are and address them.

Miller shared literacy’s “big five,” which are aspects of how a child learns to read: phonemic awareness, phonics, accuracy and fluency, vocabulary development, and comprehension. Miller said mClass tests these important aspects using eight specific measures or skills. Teachers then use this data to assess if students are well below benchmark, below benchmark, at benchmark, or above benchmark. These designations help teachers group students for guided reading activities and know which students need intensive support.

Progress monitoring, or “skill-specific, frequent, ongoing assessment,” helps teachers see if the interventions they are using, especially for at-risk students, are working.

“It’s like if you were on a diet and you wanted to step on scale. Did what I just do work? It’s not to say you’re measuring the kid, you’re measuring whether or not… the instruction reaches the kid… It’s this data that is critical to being able to make those on-time decisions,” said Miller.

Miller said services from when children are born to when they enter kindergarten are critical for how they come to school. In the last five years, she said Wake County students have gone from 20% to 42% in meeting kindergarten readiness benchmarks when they come to school. When it comes to third-grade reading proficiency, literacy depends heavily on what school within the county the child attends.

“At the end of grade three, we have some of our schools that are at 92%, and then we have some schools that are at 40%,” Miller said.

She said there are several conditions that must be true for the Read to Achieve program to work. For example, teachers need to have high-quality literacy instruction in preparation programs.

“We still have an issue across this country where at the university level, we are still teaching only one approach to reading,” she said.

Teachers also need high-quality phonics programs and tools to analyze and interpret data.

School accountability and turnaround

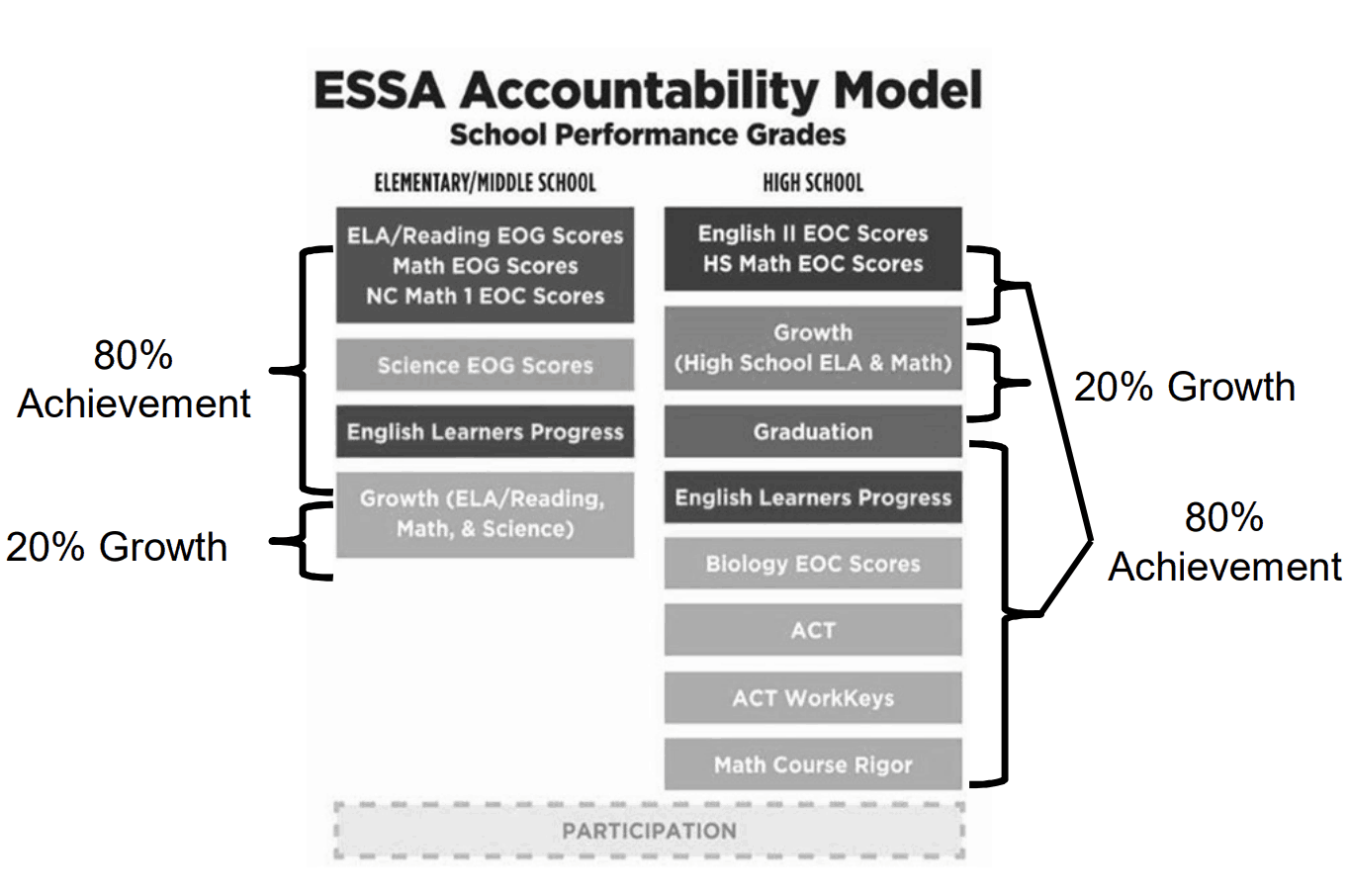

Commission members also discussed school- and district-level accountability. Since 2013, the state has used an A-F grading system to assess the performance of schools. Each letter given to a school is calculated based on 80% achievement (test scores) and 20% student growth. Low-performing schools are schools that receive a D or an F and do not exceed the state’s growth standards. The following table breaks down where exactly those scores come from.

Scott Marion, executive director of the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment, shared what comprises a balanced assessment system based on this research paper by Marion and his colleagues.

He said most assessments should be done at the classroom level and should not have accountability measures attached to them. Marion spelled out five criteria for a balanced assessment system: comprehensiveness, coherence, continuity, efficiency, and utility.

For information on each of the criterion, check out his full presentation below.

So, what does the state do with the school assessment data it collects? Over decades, several efforts have been made to intervene in schools that are identified as low-performing. Pat Ashley, cohort director of N.C. State’s Educational Leadership Academy, shared an overview of those efforts.

Ashley said that since an accountability structure has been in place and schools have started to be labeled as low-performing, state and federal interests have been at play in what should happen in those struggling schools.

“Within the last 25 years, we’ve been operating at any given time with more than one definition of what a low-performing school is, with more than one definition of what being turned around can mean, more than one definition about what strategies we should use to get continuous improvement. We’ve had variability in the resources and, every once in a while, not only is the state and federal government trying to turn around the school, but so is the local entity, and that’s another layer of competition sometimes in what’s happening.”

Ashley said since the current A-F grading system has been in place, there has been a large increase in the number of schools identified as low-performing but fewer schools actually supported by the state. Under previous definitions, there were around 100 low-performing schools in the state. According to her presentation, in 2016, out of the 581 schools considered low-performing, 75 received school support from DPI. In 2018, that number was 35 schools.

“We have a much larger percentage of schools identified as low-performing because of the way that definition works. The companion to that has been a drastic reduction in services from the state to support those schools,” she said. “So the number identified has shot up, and the number of schools helped has shot down.”

Ashley said that among the different turnaround strategies, leadership in a school matters a lot.

“The story always ended quickly, though, if there was no effective principal,” Ashley said. “That seems to be an absolute pre-requisite to having an effective school. Without someone in that principal position who can guide the mission and frame the conversation about continuous improvement, it will not go.”

Ashley said that turnaround time also matters, as well as developing school improvement plans that are not checklists but get at the root of school’s problems, strengthening the teacher and principal pipelines, providing professional development for educators and leaders, and looking at community health rather than just focusing on academics.

Ashley’s full presentation is below.

Maria Pitre-Martin, deputy state superintendent, shared how the state is redesigning its efforts to support districts. Based on an outside analysis by Ernst & Young that Superintendent of Public Instruction Mark Johnson called for last year, several recommendations were given to the department on how to increase effectiveness. One of those recommendations had to do with how the department relates to the districts it serves.

Pitre-Martin said, beginning in the 2019-2020 school year, regional teams with case managers and a variety of support staff will serve regions and districts based on their needs. Pitre-Martin said data will inform how involved the team members are in the district. Services will be more consultative if data is high. If data is low, “that’s where we become more intensive and strategic in support,” she said.

She said the department is developing a process for districts to request certain services, and, by the start of the summer, lists of regional case managers and team members, along with contact information, will be sent to the superintendents and made publicly available. The case managers are new positions, but the rest of the team members are current staff DPI members.

For more information on the state’s redesign, find Pitre-Martin’s full presentation below.

The commission has scheduled three final meetings: May 14, June 4, and June 25. All meetings are expected to be in Raleigh.