After recruiting, training, and inducting a teacher, what does it take to keep them in the classroom? Answering that question was the focus of the Governor’s Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education during its meeting last week. The commission heard from teachers, principals, district leaders, and policy experts about first-hand experiences with teacher retention, the research behind retaining high quality teachers, and six districts that are piloting advanced teaching roles and career pathways.

Created by Gov. Cooper in 2017, the commission has been working since Nov. 2017 to determine what it will take for North Carolina to meet its constitutional commitment of providing equal educational opportunity to all students. According to litigation in the decades-long Leandro case, part of that commitment is staffing every classroom with a “competent, certified, well-trained teacher” who provides “differentiated, individualized instruction, assessment and remediation” to students. In previous meetings, the commission addressed teacher preparation and recruitment, along with other aspects related to the Leandro commitment like school funding, early childhood education, the principal pipeline, and school support personnel.

The commission might hold a meeting in March, but the next confirmed meeting is April 11. The commission is also looking to add meetings for May and June, after which it is expected to release a final report.

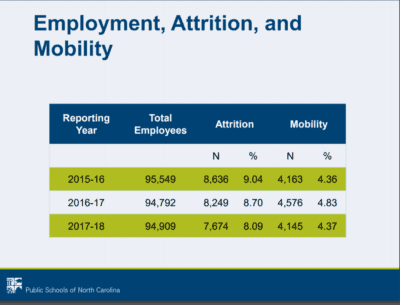

Before discussing teacher retention, the committee briefly reviewed the recently released State of the Teaching Profession report that includes teacher attrition and teacher mobility data from the 2017-18 school year. Attrition tracks the number of teachers leaving their districts for any number of reasons, including being terminated or leaving for personal reasons. Teacher mobility is defined as a teacher leaving their district but remaining in education elsewhere in the state.

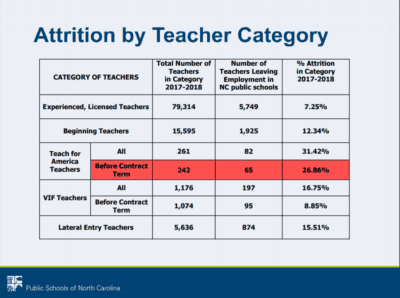

The statewide attrition rate for 2017-18 was 8.1 percent, slightly lower than 8.7 percent in 2016-17 and 9 percent in 2015-16. Of the almost 95,000 teachers employed in the state between March 2017 and March 2018, just over 7,600 of them are no longer employed in North Carolina public schools. The attrition rate for just beginning teachers — those with fewer than three years of experience — is around 12 percent, and the attrition rate for lateral entry teachers is around 15.5 percent. These rates are both substantially higher than the attrition rate for experienced, licensed teachers (roughly 7 percent).

Teacher working conditions

Dawn Shephard, Chief Operating Officer of the Center for Optimal Learning Environments, provided an overview of the results from the 2018 North Carolina Teacher Working Conditions survey. The survey was established and first administered in 2002, making North Carolina the first state in the country to study teacher working conditions. Since then, it has been administered every two years.

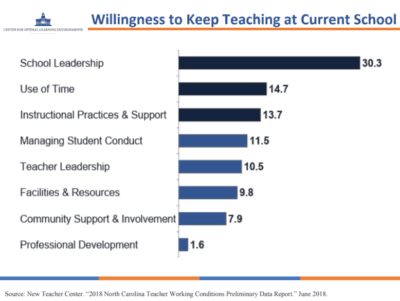

The survey looks at qualitative relationships between teaching conditions, student learning, and teacher retention using eight major constructs: use of time, facilities and resources, community support and involvement, managing student conduct, teacher leadership, school leadership, professional development, and instructional practices and support. 2018 was a record-setting year for the number of survey respondents, with almost 96,000 teachers participating, 16 percent of whom were beginning teachers.

According to Shephard, if teachers have the working conditions they need to succeed, they are more likely to remain in the classroom.

“Across North Carolina and the nation, where similar surveys are given, it has been found that understanding and improving these teacher conditions result in increased student success, improved teacher efficacy and motivation, and enhanced teacher retention,” said Shephard.

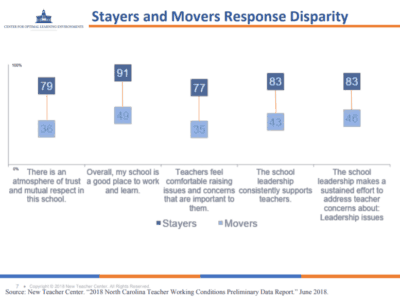

The 2018 survey found that teachers’ perceptions of the school leadership have the greatest influence on the decision to stay or leave. The next most important factors in a teacher’s willingness to keep teaching at their current school are use of time and instructional practices and support.

In addition to reviewing the aggregate results of the survey, Shephard emphasized the importance of breaking the data down by years of experience, the level of school, and teachers versus administrators. For example, fewer teachers in elementary and high schools leave when there are high levels of support and involvement from the community, whereas managing student conduct was a significant predictor of teacher attrition at the middle school level.

Shephard also shared key findings from research by Dr. Richard Ingersoll. One finding was that students in schools with higher levels of school leadership and teacher leadership perform at least 10 percentage points higher in both mathematics and English proficiency on their state assessments, after controlling for demographic factors. Ingersoll also finds that the imbalance in the implementation of key school and teacher leadership elements is exacerbated in high poverty schools, resulting in higher teacher turnover in those schools and placing students at an even greater disadvantage.

View Shephard’s full presentation here.

What are your education priorities for North Carolina? Join the People’s Session, an online project that allows you to weigh in on policy issues and add your own priorities. Click here to begin.

Teachers and district leaders weigh in

Next, the commission heard first-hand insight from teachers about the challenges to retaining high-quality teachers and what the state can do to address those challenges.

Dayson Pasion, an instructional coach at Graham Middle School in Alamance-Burlington Schools, said school leadership is the biggest challenge to teacher retention.

“In my nine years of teaching and coaching at Graham Middle, I’ve had a new principal every other year, so it’s hard to build consistency and culture and climate, let alone improve a school, especially a school like Graham Middle that’s identified as Title I,” said Pasion. “I’ve seen a lot of teachers go from our school to other schools or outside of the profession because of a lack of strong consistent leadership at the school building level.”

NaShonda Bender-Cooke, special education department chair interventionist at Carroll Magnet Middle School of Leadership in Technology in Wake County, said a lack of human resources is another challenge to teacher retention.

“We don’t have a social worker at our school, we don’t have a school nurse there every day,” said Bender-Cooke. “Our students have needs, and the one or two teachers in the classroom where the number of kids has increased don’t have the training or resources to address those needs before we can get to the academic questions in the class.”

Mark Townley, a former teacher and the current program manager of the Kenan Fellows Program, said the reason he left the classroom was due to school leadership and a lack of flexibility and autonomy. After a leadership transition at his former school, Townley said the micromanagement of the school changed everything. For example, this change impacted his ability to drive students to field trips and provide them with experiential learning opportunities.

Bender-Cooke said engaging, appropriate professional development could serve as one way to address some of the challenges to teacher retention.

“A lot of times, teachers are not given the opportunity to choose their professional development. We are told where we need to go during our teacher work days,” said Bender-Cooke. “And we are the ones in the classroom that know what we need — training on how to identify trauma, what to do next, what we can do immediately … professional development is another way to retain teachers, spread knowledge, and also make them feel supported.”

Commission member Leslie Winner said the state budget used to include funding for teacher professional development, but it was cut in part due to teacher complaints that the provided professional development was a waste of time.

“If the state were going to put professional development back into the state budget … how should the state structure it in a way that is more likely that it’ll be used for things that teachers feel like help them and less likely that teachers grumble about the school system wasting their time?” said Winner.

Townley credited teacher academies for keeping him in the teaching profession for 20 years. At these academies, he had the opportunity to engage with educators from across the state in his subject area and receive a stipend since they were held during the summer.

Pasion said the state should also consider what happens after the professional development ends.

“If there’s no structure or support to follow up, a lot of that professional development gets lost. Having that human capital in the building, whether it’s a coach or some type of hybrid role, having that follow up after the professional development is extremely critical.”

The commission also heard from Frances Herring, associate superintendent for Lenoir County Public Schools, and Elizabeth Pierce, principal at E.B. Frink Middle in Lenoir County. Herring shared information about the TIP Teaching Scholars Award program, which is a partnership with the NC State College of Education and The Innovation Project to create a pipeline of teachers for rural areas of the state. In Lenoir County, the TIP Teaching Scholars program is providing housing for a NC State student to complete her student teaching in the district. When she returns in the fall to become a full-time teacher in Lenoir County, she will receive a $2,500 stipend every semester.

Addressing the teacher shortage via teacher retention

Teacher retention is a critical factor in solving teacher shortages. According to Linda Darling-Hammond, president and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute, nine out of 10 teachers who are hired each year are hired to replace teachers who left the year before, and two-thirds of the teachers who leave aren’t retiring. Darling-Hammond shared the following findings from research about the main issues regarding recruiting and retaining teachers:

- Salaries and compensation: Places where teachers earn salaries that are competitive with other industries that employ college graduates are more able to recruit and retain teachers, especially in fields like math and science where there are more career opportunities outside of education. On average in the United States, teachers tend to earn 20 percent less than other college graduates, which reaches a 30 percent differential over the course of their career. In North Carolina, teacher pay is about 37 percent below that of other professions.

- Working conditions: This includes conditions like having a reasonable class size and the appropriate materials to teach, but also includes the teaching and learning conditions that allow teachers to be efficacious and effective. For example, community school wrap-around support models help retain teachers because they can be more effective in their teaching if kids are getting the other things they need, such as food and mental health supports.

- Nature of the accountability policy: When schools are publicly labeled with a low school performance grade, and when there are threats of sanctions and a negative reputation associated with those grades, teachers and principals tend to leave those schools in search of places where the work is easier, the resources are better, and the respect and support is stronger.

- Preparation: Those who are better prepared for teaching tend to remain in the profession at much higher rates than those who come in under-prepared. Strong induction programs keep teachers in the classroom.

- Mentoring and coaching: If beginning teachers get strong mentoring, particularly if it is a mentor in their content area that can help them in curriculum development, teacher retention is increased.

Advanced teaching and career pathways

A lack of career pathways may push teachers to become school administrators or leave the profession entirely, as they don’t have opportunities to advance their career without doing so. One solution for this issue is advanced teaching roles. Advanced teaching roles allow highly-effective teachers to advance their career by taking on new responsibilities within the school, increasing their access to professional development, and supplementing their salary — all while they remain in the classroom for at least a portion of the day.

A look back

Trip Stallings, director of policy research at the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, presented an overview of supplements and incentives for teachers in North Carolina and shared the preliminary findings from an evaluation of advanced teaching role programs across the state.

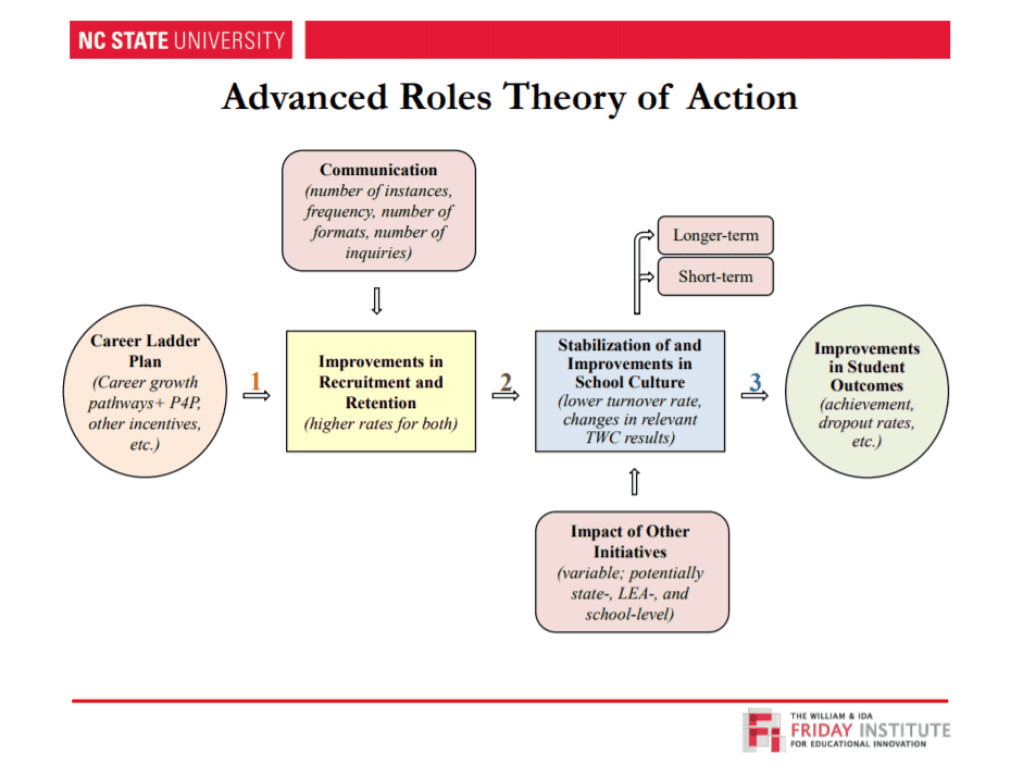

Stallings described the shift from a traditional incentives-based theory of action, where pay for performance and other incentives are use to improve student outcomes and teacher recruitment and retention, to an advanced roles theory of action, described in the image below.

Between 2010 and 2014, over $76 million was invested in strategic staffing plans for districts across North Carolina, some of which was part of Race to the Top funding. Stallings emphasized the need to learn lessons from past experiments when designing new programs.

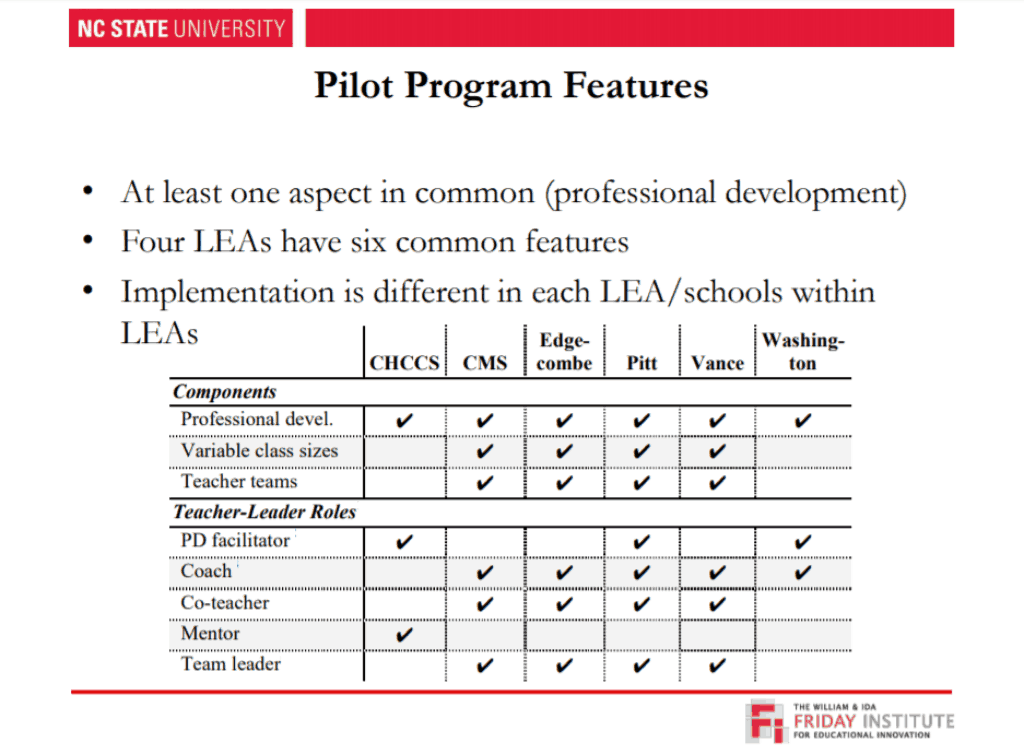

In the 2017-18 school year, six school districts received funding to run three-year advanced teaching role pilot projects overseen by the State Board of Education and the Department of Public Instruction (Section 8.7, SL 2016-94). The Friday Institute is conducting an evaluation on these pilot programs, listed below, which each have different features.

Initial qualitative findings from this evaluation include increased quality of classroom instruction, increased attractiveness of the teaching profession, and increased retention of high-quality classroom teachers. Stallings also noted the quantitative limitations of the evaluation, including the short lifespan of the pilots and the differences in the structure and implementation of the programs across LEAs.

“When I get to the end of this process, I won’t be able to tell you causally that advanced teaching led to these results. I’m going to have some correlational … but I’m not sure I’d get hung up on that,” said Stallings. “It again goes back to this issue of whether or not we want the student scores to be the primary or only outcomes. And there are a lot of other things worth measuring.”

In closing, Stallings recommended the need to fund multiple, better-controlled differential pay pilots that build on past efforts, and to plan for the sustainability of such programs.

View Stallings’ full presentation here.

Pilot programs share updates

In the final session of the day, commissioners heard from four of the advanced teaching roles pilot districts about how their programs work.

Project ADVANCE in Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools has three key features: credits for practice and outcomes, levels for career advancement, and roles. The credits for practice and outcomes allow for ongoing professional development in four key areas: data literacy, content, instruction, and diverse populations. When teachers accrue enough credits, they advance to the next level and their salary increases with each transition. The third component is standardizing advanced teaching roles — such as instructional coaches and mentors — and aligning them to the learning that teachers engage in through the different levels of Project ADVANCE.

“When districts compensate based on years of service and credits earned, they send a confusing message about what matters most. There’s not really a connection between years of service and improved student growth or student outcomes,” said Shauna Martin, director of professional learning and Project ADVANCE. “Our goals for instructional excellence and closing achievement gaps are tough, but we feel this project will help us transform student experiences.”

In Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Success by Design offers professional development and advanced roles for teacher-leaders and school-leaders. The program funds roles with existing resources by exchanging vacant teacher positions for advanced teaching roles or using Title I funding. By using resources that schools already have at their disposal, the project is more sustainable than it would be if it was grant-funded.

In the 2018-19 school year, 40 schools participated in the program with 184 teacher-leaders and 55 multi-classroom teachers supporting another 311 teachers. The grant funding supports professional development opportunities for current teacher-leaders, candidates in the talent pool, administrative staff from Success by Design schools, and district leaders.

Melissa Stormont, program manager for Success by Design, said having class size waivers is a huge asset to the program.

“Without having the ability to have larger classes, we wouldn’t be able to do this. We are getting good teachers in as front of as many students as possible,” said Stormont.

Edgecombe County Public Schools implemented Opportunity Culture, an initiative of Public Impact. The Opportunity Culture advanced teaching roles in the district include multi-classroom leaders, expanded impact teachers, and reach associates, each of which have increased responsibilities in the school and receive salary supplements. As with Success by Design, these roles are funded through the existing school budget by trading in vacancies and using Title I funds.

“The thing I’m most excited about early in this process is the transformation we’re seeing of school culture. It’s changing the way teachers teach, it’s changing the way we look at data, it’s changing the way we open our classrooms,” said Erin Swanson, director of innovation for Edgecombe County Public Schools. “We’re seeing that innovation is possible, innovation isn’t as scary as people once thought it was, and I think that’s really helping us move things forward in Edgecombe.”

In Pitt County Schools, the R3 Career Pathways Program — which stands for recruit, retain, and reward — has three programs. The Key Beginning Teachers induction program is a one-year program to engage beginning teacher leaders. The teacher leadership institute is a four-year pipeline program that includes financial support for teachers to receive their National Board certification. The last program is career pathways which allows teachers to take on roles like multi-classroom teachers and co-teachers.

Seth Brown, Director of Educator Support and Leadership Development for Pitt County Schools, shared things the state could do to help programs like R3, such as increasing investments in teacher leadership, increasing flexibility in funding streams, and increasing calendar flexibility.

“We are pulling teachers out of the classroom eight to 10 days a year,” said Brown. “If we had a week before, or a week after, or whatever we decided — what if we could train them one day a month or here and there at strategic times so we are training them when kids aren’t in the classroom?”

In January, the second round of advanced teaching roles grants were announced, and implementation in those four districts will begin in the 2019-20 school year.

Commission member Mark Jewell, who also serves as the president of the North Carolina Association of Educators, voiced concerns that supplementary pay through programs like advanced teaching roles may be used as a band-aid in place of actually fixing “the very broken salary schedule” in North Carolina.

Reflecting on the meeting, commission member Jim Deal said that one size doesn’t fit all, and increasing flexibility to local districts would allow them to determine what’s best for their students.

Commission member Leslie Winner responded with the following:

“I feel endlessly puzzled by how much we can expect flexibility to allow folks to use existing resources better, and how much it just takes more resources — no matter how well they’re using it. Every rubber band stretches so far, and then it breaks.”