Is all teaching created equal?

Lost in the shuffle of North Carolina’s debates in 2014 about whether and by how much to raise teacher pay was a fundamentally more important question:

Should teacher pay be based on experience and credentialing alone – that is, should it be the same for all teachers who have similar levels of experience and backgrounds – or should other factors – performance, duties, or even geography – also be considered?

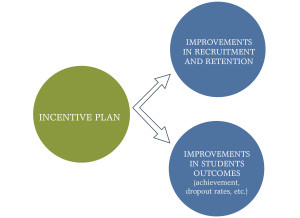

The question matters because of its growing popularity as a way of thinking about how to impact several educational outcomes. Pay differentiation (paying different salaries to teachers with the same years of experience) has been suggested as a way to recruit teachers to the state or to struggling schools; incentivize teachers-in-training to license in hard-to-staff subject areas; and, most typically, reward and retain teachers who are deemed effective, based on their students’ achievement (“pay-for-performance”).

But does pay differentiation actually work? If by “work” we mean that it directly, immediately, and positively impacts student academic achievement, then the answer is a qualified “no.” Carefully-constructed research studies offer little evidence that incentives – no matter how big – increase student achievement outcomes. If we broaden the definition of “work” to include other outcomes – such as recruitment or retention – the answer is “maybe,” depending on the circumstances.

Moving beyond pay differentiation

So, does this mean that differentiating pay is a waste of time and money? Not necessarily. Before abandoning the idea, we first may need to shift our thinking with respect to what we hope differentiation will achieve, and how quickly it will do so.

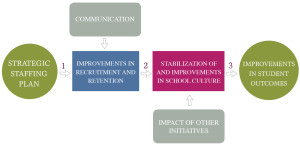

Though it may sound strange at first, the first step in this process is to take student outcomes out of the equation for the short term. Instead, we might be better off replacing these with a goal for schools to build environments in which positive student outcomes are more likely. In other words, we need to move from a narrow differentiated pay-only perspective to a broader strategic staffing perspective – one that emphasizes purposefully redistributing more effective educators into lower-performing districts, schools, and classrooms.

There are several differences between strategic staffing approaches and the traditional one-size-fits-all differentiated pay approach. First, these approaches often include more than one type of incentive – differentiated pay among them, but also things like housing for teachers and access to special equipment. They also vary in how incentives are earned; some reward teachers based on performance, but others reward differences in responsibilities, in leadership, or even in the challenges of different teaching assignments. Furthermore, the plans do not assume that all we need in order to get more out of teachers is financial motivation; instead, they assume that some teachers are better fits for some teaching situations than others. They move teachers among schools and classrooms in ways that maximize available talent to meet a district’s or school’s specific needs.

Most importantly, most of these models are part of longer-term efforts to reduce teacher turnover and change school cultures. Only once those factors are under control can student outcomes change in meaningful ways.

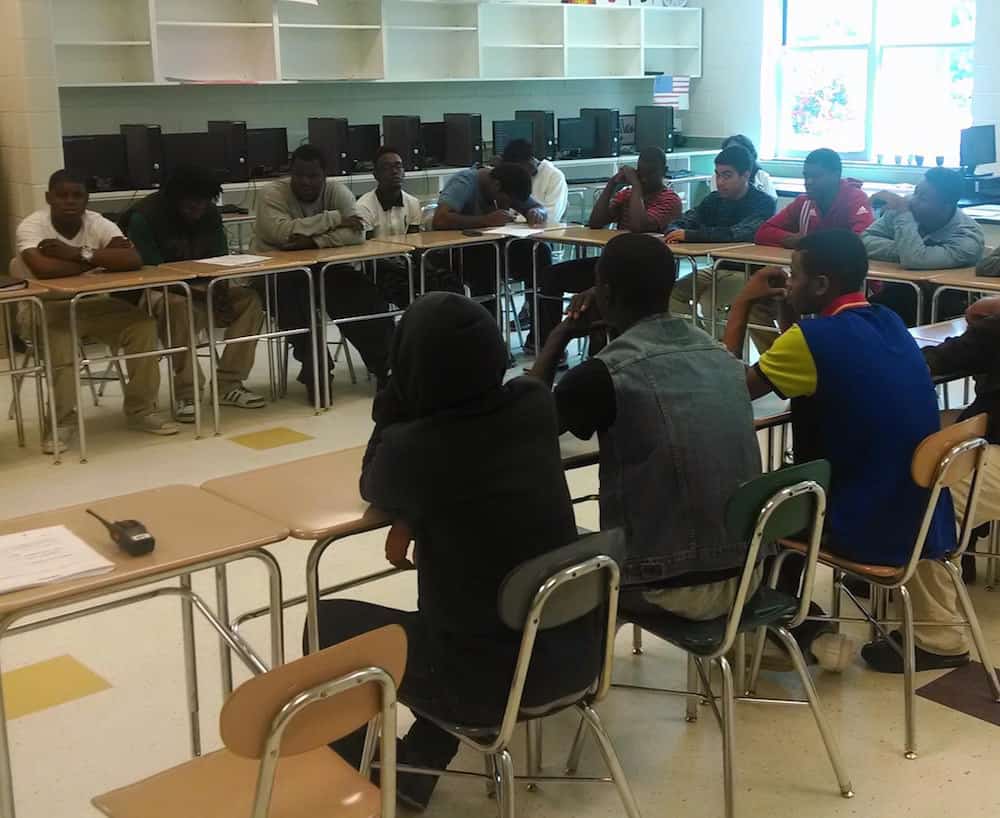

Strategic staffing in action

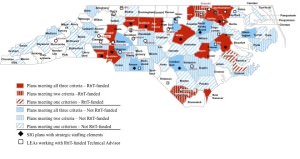

Why is the second model more likely than the first to work in our schools and districts? Put simply, as much as we would like to think of schools and districts as uniform places with common characteristics, the truth is that they are about as different as can be imaginable in the same state. Consequently, what works in Murphy is not likely to work in Manteo.

Our schools and districts already understand the importance of customization, and several have developed diverse plans. For example:

- Columbus County provides special training for lead teachers who support the highest-need schools in the district.

- Winston-Salem/Forsyth County prepares teachers to work in struggling schools and provides recruitment and retention bonuses for teachers in those schools, with significant additional awards for effectiveness.

- Guilford County’s Mission: Possible plan includes a recruitment, retention, and performance-based compensation system for educators who teach in certain schools.

- Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s Project L.I.F.T. school redesign initiative differentiates teacher roles and responsibilities and then matches compensation to those roles and responsibilities.

- Educators employed at one Moore County school are evaluated frequently to determine specific needs and are then provided with individualized professional development. In exchange, they receive significant bonuses.

Making strategic staffing work for North Carolina

The state and districts can take several steps to help us better understand how well these strategic staffing approaches work:

- Direct resources to strategic staffing plans rather than to incentive-only plans.

- Develop a communications plan. Communication is particularly critical to the success of recruitment and retention components.

- Design plans with school environment goals rather than student achievement goals.

- Plan for sustainability. Districts and schools will need help pursuing funding and planning for transitions to new funding several years in advance.

- Work together across school district boundaries. Interested districts need ways to share their experiences and learnings with each other.

- Explore multiple plan options. Districts should experiment with multiple approaches to develop optimal plans for their specific conditions.

- Review the latest research. Data and evidence about the feasibility, sustainability, and effectiveness of strategic staffing continues to expand.

- Conduct rigorous evaluations. Figuring out whether strategic staffing will have the impact we hope for will require longer-term evaluation.