Lisa Troy is searching a file cabinet for the pictures her elementary students at W.H. Knuckles drew last year. They sound jarring: rain drowning homes; a family driving while completely surrounded by water, images of displacement, images of loss, crayon-colored blue everywhere.

“It’s here somewhere,” the school’s second-year principal says, now searching piles next to her desk.

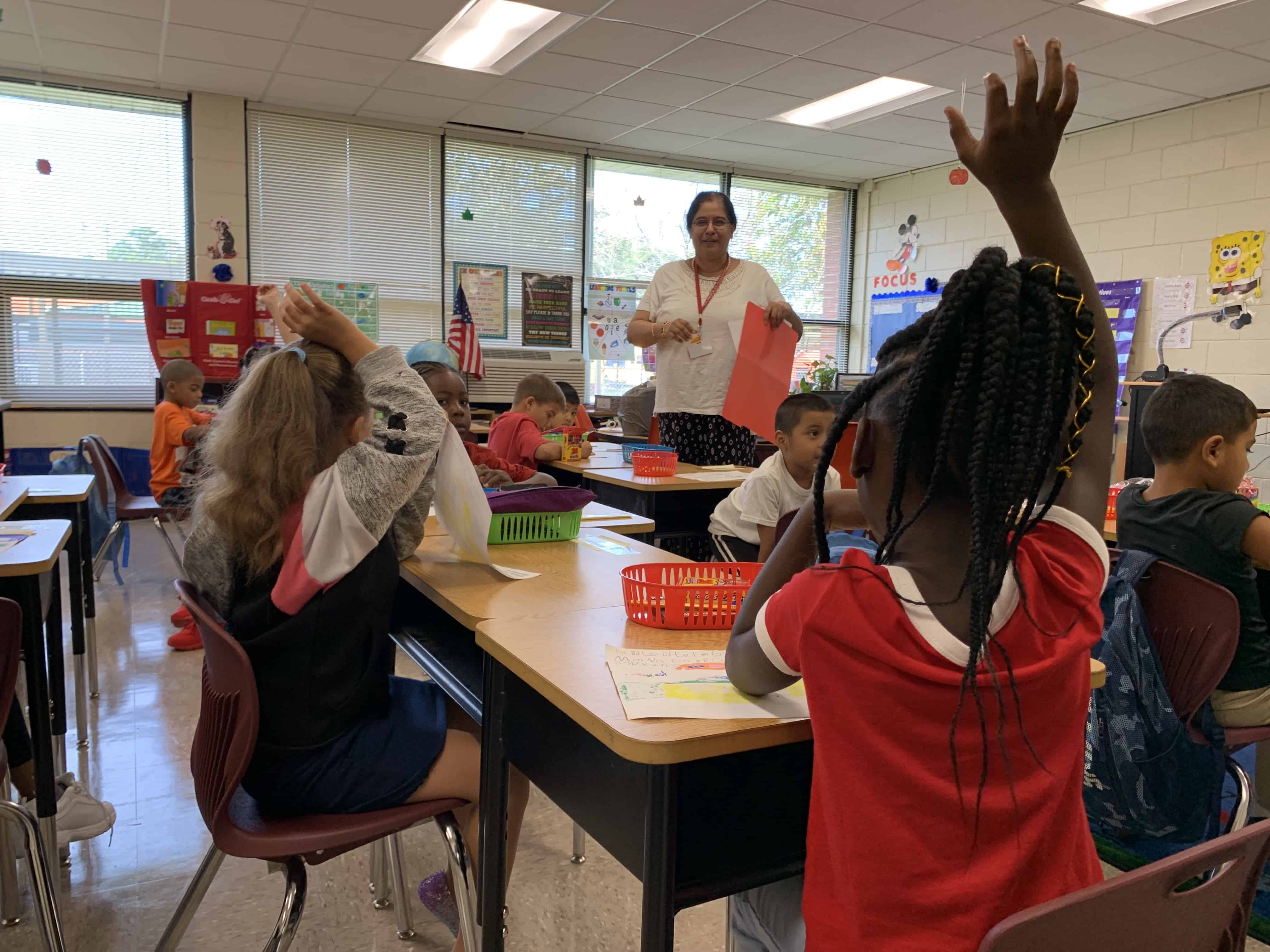

The pictures tell a story about the impact of two hurricanes in three years on one community — a story of why kids in this South Lumberton school get more anxious when it rains, and a story of children searching for their friends after classes finally resumed but instead hearing that classmates had been displaced and their families left the county.

“They’re here, I just saw them,” Troy says, abandoning her search with a sigh. “They tell the story.”

But only part of the story.

In communities hit hard by increasingly frequent storms, the wind and rain are only the beginning. Other conditions — such as lack of affordable housing, post-traumatic stress, and loss of industry over decades — all contribute to exacerbate the storms’ effects and make recovery more difficult.

All of these conditions have beset Robeson County, and in the Public Schools of Robeson County (PSRC), these conditions have stirred a long-brewing financial storm within the school system. As the flood waters receded last year, they laid bare wrecked homes and businesses — as well as a district’s severe financial distress, public frustration toward the school system, and infighting between a superintendent and the school board.

“It didn’t just start with Hurricane Matthew or Hurricane Florence,” Superintendent Shanita Wooten said. “… But I think that we probably could have done things a little differently before Florence. Our finance officer told us last summer, there’s some cuts you’re going to have to make. But then we were out for five weeks, and we didn’t even know how we were going to open. And with the age of the facilities, being hit with another storm so soon after Matthew, it just took a toll on our buildings and our budget.”

“And if another one comes around this time,” she added, “I don’t know how we’re going to make it.”

The Matthew effect

Hurricane Matthew struck North Carolina in October 2016, hitting Robeson County harder than any storm in recent memory, and harder than Florence would two years later. Before Florence even hit, PSRC was already overwhelmed with hurricane after-effects.

Matthews’ carnage included the permanent closure of West Lumberton Elementary in the western, mostly Lumbee part of town. It saturated and scattered hundreds of residents in the majority-black South Robeson community. It sent families fleeing to Winston-Salem, Fayetteville, and elsewhere across the state.

In 2016, the district lost 447 students. In 2017, it lost 493 more, bringing the post-Matthew total to 940.

According to Wooten and comments made by the school board at their meetings, some of those losses were parents sending their children to charter and private schools within Robeson, frustrated with the state of PSRC. In another case, the students didn’t move at all. The state moved Southside-Ashpole Elementary from the district into its new Innovative School District. But in many cases — and the school district believes in most cases — these were families displaced by the 2016 floods who never came back.

The dropped enrollment meant millions in lost funding from the state. The district couldn’t afford to pay as many personnel for the 2018-19 school year. Still, in the summer leading up to Florence, PSRC didn’t lay anyone off. Not because they were unaware of financial woes, but because it’s hard to make that call in a community already crushed by the loss of tobacco and textile jobs overseas and of small businesses to storms.

“One thing that we have talked about over and over again is we have too many employees,” Wooten said. “But, realistically, someone who leaves today is not going to find a job tomorrow, and they may not find one for the next five years. So where does the burden go? Who picks that up? Because it impacts all of Robeson County. A lot of our employees are from Robeson County — they were born here, they went to school here, went to college here, teach here, they’re from here.”

The budget shortfall would present itself at the end of the school year. They would figure it out by then, Wooten believed — except, their attention was about to be needed elsewhere.

A long summer before Florence

Hurricane Florence was born as a tropical wave off the western coast of Africa in August. Hardly anyone was tracking it until August 28, 2018.

It bellowed westward off the coast of Senegal, drinking in the air’s high moisture as it began making its way to North Carolina. It was traversing a large belt of low pressure near Cape Verde when the National Hurricane Center, which began monitoring the system days earlier, dubbed it Tropical Depression Six.

For the school district, after a long summer of increasingly poor financial updates and growing frustration from local educators, there were other things competing for attention.

The district’s financial officer, Erica Setzer, had gone over the expected state funding loss. She reported the surplus personnel. She talked about a growing problem of long-term substitute teaching in classrooms — a seven-figure issue without a solution at the time.

Also that summer, Wooten began a slew of unpopular administrator changes, moving principals to assistant principal roles and moving some assistant principals back into the classroom. One school board member pulled her aside as the summer wound down to say he’d never seen that many administrative changes over a single break.

“We had to strengthen the leadership pool,” Wooten said. “We had to staff our buildings with the most qualified individuals.”

It put her at odds with many county educators, though.

As the summer wound down, Setzer gave Wooten another disheartening financial update — one that wouldn’t help her popularity problem: the district would have to scrub summer teaching positions after the school year. The financial insecurities led to a tightening of purse strings when it came to teacher and school funding requests. Already out of favor with some district educators, the central office turned down requests for supplies, tutors, and other projects.

“Sometimes they don’t understand the why,” Wooten said. “When the central office folks are making decisions, when we say, ‘No, no, no,’ they think we’re not being sympathetic. That we’re not hearing them. But truly, we’re having trouble paying for things, paying our bills. I’m just trying to stay afloat. And that causes a rift between the central office and our schools.”

The school board asked the county commissioners for help. But the county commissioners were concerned about financial management.

“We don’t want a Band-Aid approach,” county manager Kellie Blue told the Robesonian. “We would like to see a strategic plan from the Board of Education.”

Wooten said, “Our funding from the county commissioners has not increased significantly, but they’re saying, ‘Why do you want us to keep giving you more money when you’re not committed to making tough decisions like closing schools and consolidation?’ They want us to build new schools but they’re only going to be committed if we have the courage to make tough decisions.”

As the long-brewing financial storm gained turbulence, back in Cape Verde, storm watchers noticed Tropical Depression Six intensifying, also. It stunted temporarily behind moderate wind, but it started to form strong banding features typical of a tropical storm. It was Sept. 1, and the National Hurricane Center was ready to name the sixth storm of the season.

They named her Florence.

Florence approaches

Troy was barely settled into her new job at Knuckles when Florence updates started airing on television. Still, she didn’t miss a beat preparing. During the second week of classes, Florence achieved major hurricane force. The weather reports were unsure where it would hit and correctly predicted its downgrade in force.

Troy heard all of that. But she doesn’t take chances with weather reports anymore. Not after what she’d been through.

Three years ago, Troy barely escaped when Matthew hit. She remembers the rains the day before, but she was out about town running errands and taking coffee to her parents. She woke up the next day with no power and more rain. There was standing water outside, but not very high. In fact, she remembers her neighbors calling over that they were putting food on the grill.

That changed quickly. Her neighbors called over again. The waters were rising, and they heard it would reach rooftops. She quickly packed a bag and as dusk fell, she and a group of neighbors waded through waist-high water, imagining the fish and snakes and God knows what else that floated within. It was hours before she spoke to her parents. She fled to Fayetteville and did not make it back to Lumberton to see her parents until a week later. She could not get to her own house for two weeks.

So by September 11, as upwelling of cold water contributed to Florence downgrading and losing major hurricane status the next day, Troy remained busy securing her school.

She and Knuckles teachers discussed messaging for children to allay their fears. They spoke to students and sent them home with information about how to prepare for the storm. Troy asked each of her teachers to sign up for a Remind account, a platform that would allow them to stay in contact after the storm hit.

Next, they moved supplies and equipment onto tables and shelves and securely packed vulnerable materials.

“We had to assume it was going to be as bad as Matthew,” Troy said. “When we were hit like that before, you don’t want to go through it again. We just prepared as best we could.”

Into the storm

Rain started falling a few days before the storm hit the coast, and as it neared Wooten began receiving flash flood and other weather alerts on her phone. The day before landfall, Florence began to slow down — which would contribute to her wreaking havoc as she entered North Carolina at a crawl by storm standards.

Florence made landfall at Wrightsville Beach on September 14 as a Category 1 hurricane with 90 mph winds — much weaker than news reports anticipated days before. But even as she weakened to a tropical storm, Florence moved slowly west to southwestward pouring torrential rainfall over the state’s southeastern counties.

Wooten was scared — “these are our families, our homes, our students,” she said. It rained in Robeson for four days. The flooding started that night, as Florence dumped more than 18 inches of rain on Lumberton.

Wooten, central office leadership, and custodians had to run a number of shelters that were housed in county schools until Department of Social Services and Red Cross officials took over. They remained after the leadership transition, dealing with emergencies as they coordinated with principals and teachers to locate students.

At the emergency operations center, they heard the 9-1-1 calls and terrified voices as they came in. Interstate 95 flooded, again, all the way from mile markers 13 to 22. The flooding wasn’t shaping up as dramatically as Matthew, but calls from the south and west parts of Robeson made evident that these communities were doused again. Meanwhile, other weather systems were taking shape. A tornado touched down south of State Road 1134, tore limbs, and felled a large oak tree.

They traveled back-and-forth between emergency operations and shelters. They got a call from one high school shelter that ran out of food. As they began moving to handle the situation, another call came in from Purnell Swett High School that the backup generator had gone down and a survivor was running out of oxygen.

As they responded to calls, the reports on school conditions began to roll in. The roof shingles had come off at St. Paul’s High School. Fairmont Middle School had internal damage from ceiling tiles falling during the storm. The entire district’s server went down, leaving it without Internet and severely limiting communication.

“I was traumatized,” said Wooten, a single mother who was herself displaced.

At Knuckles, the cafeteria was submerged. The school concocted a make-shift serving hall in the gym. They later noticed an odor in the main building and found moisture in the roof, so they had to move classes to other buildings and the administrative offices moved to the media center for all of last year.

“It’s a lot of changes,” said Troy, who said a sense of perspective helped them get through administrative challenges. “You would drive around and just to see it. I remember with the tear-out process, you could ride by and everyone’s stuff would be on the side of the road — furniture, couches, clothes, everything.”

By the time remnants of Florence emerged off the New England coast, reincarnating as Hurricane Leslie and threatening the Iberian Peninsula, the school district’s operations and financial stress went the way of the storm — off the radar.

“We were worried about the students,” said Karen Brooks-Floyd, assistant superintendent for administration and community engagement. “We were worried about how to get schools running and how we were going to open schools.”

In its wake, Florence left more than $50 million worth of damage in Robeson County, flooding more than 4,000 homes and displacing more than 500 residents — primarily in the southern and western parts of the county. It closed schools for five weeks, and it turned district leadership, principals, and teachers into recovery personnel before asking them to quickly switch back to being educators.

“When it was time for the schools to reopen, I wasn’t ready,” Wooten said. “We were working around the clock to help in the shelters and find students and get nursing supplies. We tried to meet all the needs, and it took a toll on us.”

The second storm is uncovered

As it worked to reopen schools, the district continued to struggle with operations.

In 2015, Robeson’s Exceptional Children’s Program failed to meet program requirements, meaning the district did not receive the federal money distributed by the state to provide services for students with learning differences. By the spring of 2019, they still had not received funds due to a failure to address corrective actions.

“We have different funding sources, but they’re not being maximized,” Wooten said. “We should be spending them more strategically on certain types of programs and initiatives, even mandates. We can’t do that, because we’re so busy just trying to maintain what there was in the past.”

In January, Wooten looked at the expenses with Setzer again. The district still had not controlled spending. One major expense was substitute teachers. In the past year, the district had spent $2.5 million on substitute teachers due to teacher absenteeism and an inability to fill certain positions.

By March, the central office realized enrollment was going to continue to slide. They ended up losing an additional 748 students from last year, bringing the total enrollment decline close to 1,700 since before Matthew. That translated to nearly $13 million less in per-pupil funding from the state.

For principals and teachers, it spelled more “No’s” to funding requests.

“With my background, being a teacher,” Troy said, “a teacher just makes a way. Whatever way you can. That’s what you learn to do. Of course, we would love more local funding. That’s what the desire and the goal is.”

District leaders still had no concrete cost-cutting plan, though, so county commissioners did not change their position on funding. At this point, the school board started ramping up informal discussions to address the issue, including discussions on consolidating schools.

Local infighting and a plea for help from the state

At a meeting in March, the board discussed consolidation. Mike Smith, the board chair at the time, said, “The only thing holding us up is us. I’m committed to making the hard decisions.”

As the school year came to an end, state and local dollars were used up and the district faced a deficit. They plugged the hole with insurance proceeds from losses at West Lumberton and the district’s central office. But the plug was only good for one year.

“That’s when we were running into a problem,” Wooten said. “That was put into our operating budget. However, we know those funds are not-recurring. So this year, we know we can’t use those same dollars to pay the bills. So our thing was, we have to save drastically.”

After the March board meeting, parents became nervous — particularly those in the south and west parts of the county. In response to a Robesonian article reporting consolidation talks, parent Samantha Lowry challenged the idea that focusing on what’s best for finances would achieve what is best for students.

“Why can’t we just simply see that the more kids you have in a school, the more problems you will have and the less attention a child gets from the teacher,” she said. “ … I really believe no matter what the board thinks, this decision should be in the hands of the parents and teachers because when it all boils down to it the teachers and we parents have to deal with the consequences of that decision. If you ask me our school system is messed up enough.”

Wooten said pressure from parents and teachers started shaking the school board’s resolve — at a time when she thought the resolve needed strengthening. The district would lose another 748 students by year’s end, and if they didn’t cut costs, they would be left with a $2 million deficit with no other plug for the hole.

Before consolidation talks could get far, however, Wooten made two major decisions that irked the school board and set off a power struggle that placed infighting among school officials out in the open.

The first was on May 1, when she sent letters to about 30 principals and central office personnel stating her decision not to renew their contracts. As a superintendent, however, Wooten is supervised by the school board, which could overrule this decision. Wooten informed the board they had until June 1 to “notify each of these people whether or not they would have a job.”

June 1 marked the beginning of a school board retreat, at which time Wooten planned to present a strategy for consolidation and reorganization of the central office. If they didn’t like her plan, she thought, the board could send renewal letters that evening overriding her decision.

But that would force a same-day decision. Wooten said some school board members told her they wished there was a consolidation plan in place before she sent the letters.

She wasn’t done sending letters, though. On May 14, she wrote a letter to the State Board of Education pleading for state intervention and assistance with the financial issues.

She pointed her finger directly at the school board.

“ … the school board has become an obstacle to further improvement,” she wrote. “Sabotage of the district image and financial management, along with micromanagement by board members, continues and seems to be worsening. The superintendent and board members’ contentious relationship and differing leadership philosophies have hindered the district/school improvement process. The issues between the school board and senior leadership have distracted the staff and students in the district. Ego-driven conflict at the top has slowed our progress. The resulting turmoil is jeopardizing the orderly administration of public education in Robeson County.”

EducationNC attempted several times over two weeks to contact school board members, but multiple e-mails and phone calls went unreturned.

State Board Chair Eric Davis responded, writing, “Members of the North Carolina State Board of Education are concerned about the financial status of the Public Schools of Robeson County.” He acknowledged a recent finance committee update from Setzer, expressing worry over:

- an anticipated budget shortfall in excess of $2M

- declining average daily membership since 2015 without adequate spending adjustments

- the district’s current and projected staffing levels

- use of proceeds from insurance funds to cover operating expenses.

Still, the board ultimately decided not to let go of any of the 30 employees. The school board had scheduled an appeal hearing for the 30 affected personnel for May 29, but went into closed session before hearing any appeals. They re-opened the session with a motion to renew all of the contracts.

Then-chair Mike Smith cast the tie-breaker in a 6-5 vote to renew. He reasoned that there was no plan in place to close any schools, so each of the principal roles was a mandated position and would not save money. He pointed to fixing the substitute teaching problem as a way to find savings.

John Campbell, who is now chair of the school board, told The Robesonian he was disappointed with the outcome.

“I thought we were here to work toward eliminating a $2 million deficit,” Campbell said. “ … We caved to public pressure. We’re in a hole, and we need to stop digging.”

Wooten believes the six board members who voted to renew the contracts were sending her a message.

“They didn’t even listen to a plan,” Wooten said. “It became a power struggle and they said, ‘Well, Dr. Wooten did this, so we’re going to renew them all.’”

Wooten later proposed a consolidation plan, which the board approved on June 18, that included closing J.C. Hargrave Elementary in East Robeson, Rowland Middle in West Robeson, Green Grove Elementary in Southwest Robeson, and R.B. Dean Elementary in West Lumberton. South Robeson High School would become a middle school, eliminating the high school.

“I got push back then,” said Wooten, who said she prepared herself for fallout. She knew her contract contained a buyout clause that triggered August 1.

“I knew what I was doing,” she said. “I knew I may not be around much longer.”

On July 9, the board called a special meeting to further discuss consolidation. Wooten worried because irate parents had reached out to board members prior to and at the meeting. The board made their first reversal: saying they wouldn’t close the high school at South Robeson this year — to much jubilation of the South Robeson contingent in attendance.

“I panicked that night when he said that, because there’s no way,” Wooten said. “The county commissioners won’t increase funding [without major cuts], and we will not make it through the next fiscal year.”

Wooten sent a second letter to the State Board.

“Again, the school board has become an obstacle to further improvement,” Wooten wrote. “Sabotage of the district image and financial mismanagement, along with micromanagement by board members is at an all time high. Board members who lack the knowledge of effective school district operations and transformation are making critical decisions.”

“The Public Schools of Robeson County is facing an extreme financial crisis.”

Wooten told the State Board that Robeson’s school board was making decisions that were unaffordable, that they were “unable and unwilling to make sound financial decisions,” and that the “district simply cannot sustain itself at the current level of spending and the board refuses to develop and/or adhere to any prioritized list of needs.”

She wrote that politics were influencing decisions and that underlying “issues centered on power and control continue to manifest and the ego-driven conflict at the top has now stopped any and all progress.”

Wooten knew she had upset many administrators with her personnel restructuring. Many teachers were upset with the central office because funding requests were declined amid cost-cutting efforts. Now, she was going over the head of the school board which supervises her.

“We’re not elected,” Wooten said of herself and her leadership team. “These are our jobs. So we’re willing to put the information out there. But the board members who get re-elected were scared to release certain information. But we had to, to let people know that this is our true financial state.”

That true financial state was grimmer than anyone realized. State Board and DPI members spoke with the local school board and discussed the results of a state-mandated audit. Going in, Wooten said school leaders thought they had general funds to cover a few months’ worth of operating expenses. In fact, they didn’t have enough to cover even a few weeks.

The costs associated with maintaining the high school at South Robeson were large. And on July 19, the school board reversed course again, approving a consolidation plan which tracked Wooten’s earlier proposal.

Now, Wooten promises even more changes to come. The next step is to examine class sizes in every school after the 20th day of class. Based on that, she will make staffing reduction recommendations for next year — establishing criteria early on for principals to use in ultimately making those calls.

“And that’s scary,” Troy said. “Especially as an administrator. We all have contracts. And next year could be my turn. But I know they have to do what’s in the best interest of the students, and they have to move the system forward.”

Wooten said she doesn’t like having to push for these decisions. In fact, making controversial decisions like these could mean next year is her turn to go — if not sooner. But she sees two alternatives, and only one she is willing to take.

“I didn’t wake up and just say I wanted to have a tough next five years, because now we have targets on our backs,” Wooten said. “We didn’t have a choice.”

“I knew what I was getting into. Either I was going to sit there not making a difference and the school system was going to go bankrupt, or we were going to consolidate, make tough decisions, and be unpopular for that. But for that reason, I’m okay with anything that may come.”

The consolidation announcement upset the community. Comments at school board meetings and online repeated many of the same concerns: Why did three of the closed schools have to be in the south and west parts of the county? Loss of schools means loss of businesses, the predominantly-minority communities argued. Why not push harder for redrawing district lines and change boundaries to even out the schools?

But Wooten finds comfort in early signs of financial stability since making the consolidation move. She said in previous years, the district had at least 40 long-term substitute teachers in classrooms. This year, they started with five. And every classroom has a certified teacher in it.

Still heartburn remains for Wooten and the entire school system for several reasons: the budget impasse in Raleigh, the unfavorable outlook on boosting enrollment, and the the next hurricane to come.

On the day before classes started last week, central office leadership and school board members toured the schools with a Robeson County DPI representative who asked: “Gov. Cooper just asked the other day, do you think it would be possible to make it through the school year if a budget is not approved?”

“And I was like, wow,” Wooten said. “Because we can’t even make it a whole month right now.”

And making it through the months are a necessary step before tackling the next major challenge, which is regaining enrollment. With the state of Robeson county right now, Wooten has dim hope that families who fled after Florence and Matthew will return.

“I wouldn’t be optimistic that they would come back,” she said. “I have to be honest. Until we get it together, and every single agency … can come together, why would you want to come back to a divided county?”

Meanwhile, the county is watching the weather reports with a collective pit in their stomachs and prayers on their lips. They’ve been keeping track of Hurricane Dorian, which has hugged the coasts of Florida and Georgia with its eye trained on South Carolina and North Carolina.

“It’s not a matter of if a storm is coming, but when,” Troy said. “Is it next week? And as children, and as adults, we hear storms now and people get anxious. People begin to worry. It doesn’t even have to be September. It rains hard and you just remember and think about it.”

Added Wooten: “I’m scared. This community, while it may bounce back, I don’t know how we’re going to handle that one.”