This semester, the College Board and the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics (NCSSM) joined with Public Impact’s Opportunity Culture initiative to test the remotely located Multi-Classroom Leadership model: An excellent NCSSM teacher would lead a small team of teachers spread across rural North Carolina districts, which often lack enough teachers who are prepared to ensure student success in advanced classes, including AP courses and their precursors.

So far in the national Opportunity Culture initiative, multi-classroom leaders (MCLs) lead a small grade or subject teaching team within one school, providing instructional guidance and frequent on-the-job coaching while continuing to teach part of the time.

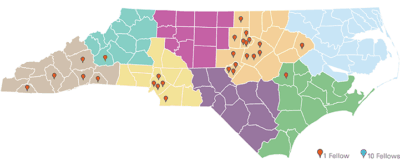

For the pilot, NCSSM teacher Maria Hernandez became the MCL for five pre-calculus teachers spread over four districts, while continuing to teach a reduced schedule at NCSSM. Along with leading and supporting the teachers, she co-taught with each teacher — sometimes leading small groups, sometimes teaching the whole class — once or twice a week via video hookup that allowed them to see one another.

Midway through the semester, I checked in with Hernandez, the team and some students to hear early impressions of the pilot’s benefits and challenges.

Hernandez took the role for its fit with NCSSM’s mission: “It’s a great opportunity, I think, to serve the state in a different way, to collaborate with these teachers. And also, I think it gives us a really good eye into the world of both the public school teachers in North Carolina but also the students who come to us from various places in the state.”

She zeroes in on her desire to lead other teachers to show students math’s real-world connections, to build their curiosity.

“Oftentimes, mathematics is kind of taught in this way that it’s handed down from people who have created it,” Hernandez said. “But there was a lot of messiness that went on and things that didn’t go right before it went right, and students do not get a sense of that. So I think in this role of multi-classroom leader, I get to bring that to the forefront with what we’re doing — helping both the teachers and the students understand that mathematics can be a place of creative thought and not just memorizing skills and facts.”

The five team teachers opted in to the pilot hoping for collaboration and the chance to learn from an excellent teacher and one another, and to see the MCL role in action.

“I get the opportunity to co-teach with her,” Stanford Wickham of Vance County High said. “We plan, we reflect, and we evaluate together, so there is timely feedback from Maria every time. And of course, it gives me as a teacher the opportunity to grow.”

Now in her 30th year of teaching, Corrette Miller of Lexington Senior High joined the team in part to expose her students — the vast majority of whom live below the poverty line — to the sort of teaching that NCSSM students get, and help expose them to the possibilities of college and beyond.

Sarah Donaldson, a second-year teacher at North Pitt High and the only pre-calculus/AP calculus teacher at her school, joined for the teamwork and coaching. “I wanted that support, I wanted to improve my teaching, and I wanted to be able to collaborate with others because I absolutely love collaboration, but unfortunately, because of the classes I teach I don’t get a lot.”

Early benefits for teachers

Hernandez’s team praises her for the relationships she has built with them — all done remotely except for one crucial, full-day “launch” of the team late last year. And they cheered the hands-on, higher-order thinking her lessons bring to their students. In all of these schools, the teachers said, students have great needs, and the teachers have been encouraged by the ways they’re learning to engage students who see math as a difficult subject.

In many of the schools, the teachers note a gap in student expectations, for which they appreciate Hernandez’s backup. “They have always been spoon-fed, or they’ve always been taking notes, so coming to my class where I say, ‘No, you’re going to do it on your own,’ that’s a big gap — and that gap is hard to manage in 90 days,” one teacher said.

Many of the teachers mentioned an early modeling lesson done with Hernandez’s guidance, in which students had to make a box from paper, determining whose box had the most volume. With tangible proof, “all of the light bulbs started going off” for her students, said Jocelyn Thammavong, who has taught pre-calculus for nearly a decade and is New Bern High’s math department chair.

Hernandez generally co-teaches — whole-class or small groups — with a teacher one day a week, observes and gives feedback another day, and meets by video conference with the whole team weekly for at least an hour. Throughout the week, the teachers stay in frequent contact by email and text as well. The teachers also receive support from a second NCSSM math instructor, Tamar Avineri, who is available when Hernandez has other duties.

Ashley Knox, a fourth-year teacher at New Bern High, says Hernandez has given her multiple ideas to incorporate not just in pre-calculus, but all her classes, such as a pod seating arrangement to encourage student collaboration.

“For the past couple of weeks, [Hernandez] has given me an action step, and we’ve discussed how we want to grow from this experience, what do I want to see in my classroom, what do I want to change, what do I want to keep the same?”

Using video recordings of their own instruction, plus recordings of Hernandez leading small groups, has been valuable, the teachers said — both for individual feedback with Hernandez as well as showing a video to the entire team for reflection.

And it isn’t all about learning where they need to improve. Part of the joy of the team’s collaboration, Thammavong noted, comes in the times when “I just think I’m on my own, and no one else is thinking the way I’m thinking, but it’s nice to see that they were agreeing.”

Early benefits for students

Miller and others noted the ways Hernandez has been able, mainly through small-group work via video hookup, to begin to build relationships with students, even from a distance, and the difference that has made in students’ confidence and willingness to speak up. In Miller’s class, which has many native Spanish speakers, Hernandez sometimes signs off from co-teaching the class for the day in Spanish. “The first time, boy, their heads jerked up, and since then they look forward to that,” Miller said.

Using Hernandez’s instructional approach “gives us the opportunity to allow our students to own their lessons — they have autonomy over their lessons; just seeing them discussing in their small groups and getting all excited and presenting themselves, that is awesome,” Wickham said. “Some students never had that opportunity to do that, and students who don’t usually talk, I can see where those students are actually coming out and are willing to say something.”

Students, of course, don’t notice the behind-the-scenes teacher coaching and collaboration. In their opinions, it’s much simpler: They get two teachers, and that’s a good thing.

“I’ve always liked how Ms. Knox explains things, but having Ms. Hernandez in the classroom [via video], too, is really beneficial, because every teacher has their own style or tips and tricks, and it’s really interesting to get two opinions,” said Rebecca Knight, a New Bern High student.

“[Ms. Hernandez] was able to get our names pretty quickly, and so she’s able to call on us and figure out, you know, who’s good at this topic or who is a little bit more shy and needs to be pushed, or who maybe needs to step back and let others have a chance.”

Knight’s schoolmate, Abraham Leonardo Jimenez-Estrada, said the teacher-on-video felt a bit awkward at first, figuring out when and where Hernandez was looking and listening to them. “But as we had more classes with her, we became more comfortable with it and, eventually, just treated it as if it was just any teacher standing in the room with us.”

Charkesta Downing, a North Pitt High student, said having another teacher’s perspective helped meet the needs of all students. “I beg my teacher every time that we have her, I literally beg to get into the groups to work with her. If I’m not understanding the lesson that’s taught during the class period, she’s able to break it down another level where I can understand it more. So having a second teacher takes the stress off of my primary teacher and ourselves because that’s like pretty much an extra 30 minutes for the students who aren’t able to stay after school, who aren’t able to come to school early. We have that opportunity to have someone else help us.”

Hernandez returned repeatedly to her theme of creating a space in which students feel free to make mistakes, and her hope that this will be a lasting, major impact on the team’s current and future students.

In a recent class, she said, students were working on a problem, when she heard a student yell, “I got it!”

“That kind of excitement — that she was happy to just holler it out — I think that says a lot to the environment that we’ve built,” Hernandez said.

Early challenges

In some schools, the technology is an issue — with only basic tools to work with and sometimes iffy connections and difficulties with audio. The team also had to deal with a misalignment of schedules among schools, because New Bern’s semester was delayed due to Hurricane Florence’s aftermath.

Because this was a pilot, teachers said they also underestimated how much work they’d be diving into. These are thoughtful, determined teachers, who won’t, as one said “slap stuff together” — so the time to understand Hernandez’s lesson plans or create their own under her guidance has taken longer than expected.

The work will, they said, make future semesters significantly easier.

“The teething pains are always the hard part,” Wickham said. “Next semester, it should be easier because we would have gone through it and so, we know exactly what it is that we should be doing with our students. … We are going to harvest things next semester from this hard work right now.”

Still, the time challenges were real. “I feel like we’re almost starting from scratch versus working on what we’re already doing — which is not necessarily a bad thing, but it’s a lot of work on our end…like I finally got kind of the groove down and the groove is no longer there,” Donaldson said. “It’s a lot more time-consuming than I was expecting.”

In North Carolina, students must take a state final exam (the NCFE) in pre-calculus; NCSSM students do not. That mismatch has caused ongoing struggles for the team’s detailed lesson planning, to determine how to align Hernandez’s strong plans, pacing, and hands-on time with the teachers’ needs to prep students for the exam.

“In a perfect world, I would do exactly how North Carolina Science and Math does pre-calculus, because what they take out and what they do and how to do things is aligned to my teaching vision — it is aligned to what I think is beneficial for students — but the reality is I have 90 days to prepare them to be successful, not only in my class but on the NCFE,” Donaldson said.

Additionally, the constraints of the pilot mean some lessons, assessments, and elements of an online platform have been build-as-you-go; ideally, remotely located MCLs and their teams would have paid time before the semester for more planning.

In a typical Opportunity Culture school, MCLs receive support from a principal or assistant principal that mirrors the support they give team teachers. For the pilot, Hernandez has a coaching phone call twice a month for an hour with Erica Jordan-Thomas, a former principal of an Opportunity Culture school in Charlotte who is now pursuing her doctorate at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Jordan-Thomas has focused on some nuts-and-bolts of team leadership, such as how to provide high-quality action steps for each teacher.

Midway through the semester, Hernandez and Jordan-Thomas were grappling with some of the challenges of providing feedback remotely. Being able to see each other on video helps, but some typical MCL techniques, such as practicing delivering a lesson, feel even less natural when not in person. The chances for miscommunication increase as well; as several educators noted, one missing piece will always be the quick hallway conversations that both build trust and get easier questions answered instantly.

For the three partners in this pilot, identifying challenges like these is precisely the purpose of the pilot. Public Impact staff works closely with the team to spot issues and develop better approaches, setting the stage for reaching far more teachers and students with this kind of support — building on the enthusiasm of participating teachers such as Vance County High’s Wickham.

“For me,” Wickham said, “I have seen growth. I’ve seen where I give my students more opportunities to answer questions by my leading them to answer a question — not actually telling them, but actually getting them to understand and to answer their question. So there’s growth in my students, there’s growth in me, and the program is a good one, which I think should continue down the years.”

For more on math modeling, see these resources recommended by Hernandez:

Guidelines for Assessment and Instruction in Math Modeling Education