When Kerry Blackwelder attended her first professional development workshop, about reading instruction, at the Hill Center in 2003, she was not sure what to expect.

“Sometimes teachers, we think we’re on an island by ourselves,” the veteran Davie County educator said. And her previous experience with professional development programs—including external- and district-led initiatives—was not always fulfilling. “They pick what they feel is best, and it might be something you don’t even teach, something that’s not at all relevant to you.”

At Hill, a Durham-based nonprofit that provides literacy programming for children and professional development for teachers, Blackwelder found something different.

“I’m not just going to learn best practices,” she said. “I’m able to network and get to know teachers that are feeling the same kind of stress I feel, and going to the same kind of issues that I am in my classroom.” After the workshops are finished, Blackwelder often stays connected—and shares experiences about what’s working in the classroom—with other teachers via Facebook.

The center’s flagship reading program, HillRAP, is a “multisensory structured language approach to reading.” When teachers participate in professional development programming to implement HillRAP, they learn about the five components of successful reading programs, as outlined by the National Reading Panel: phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

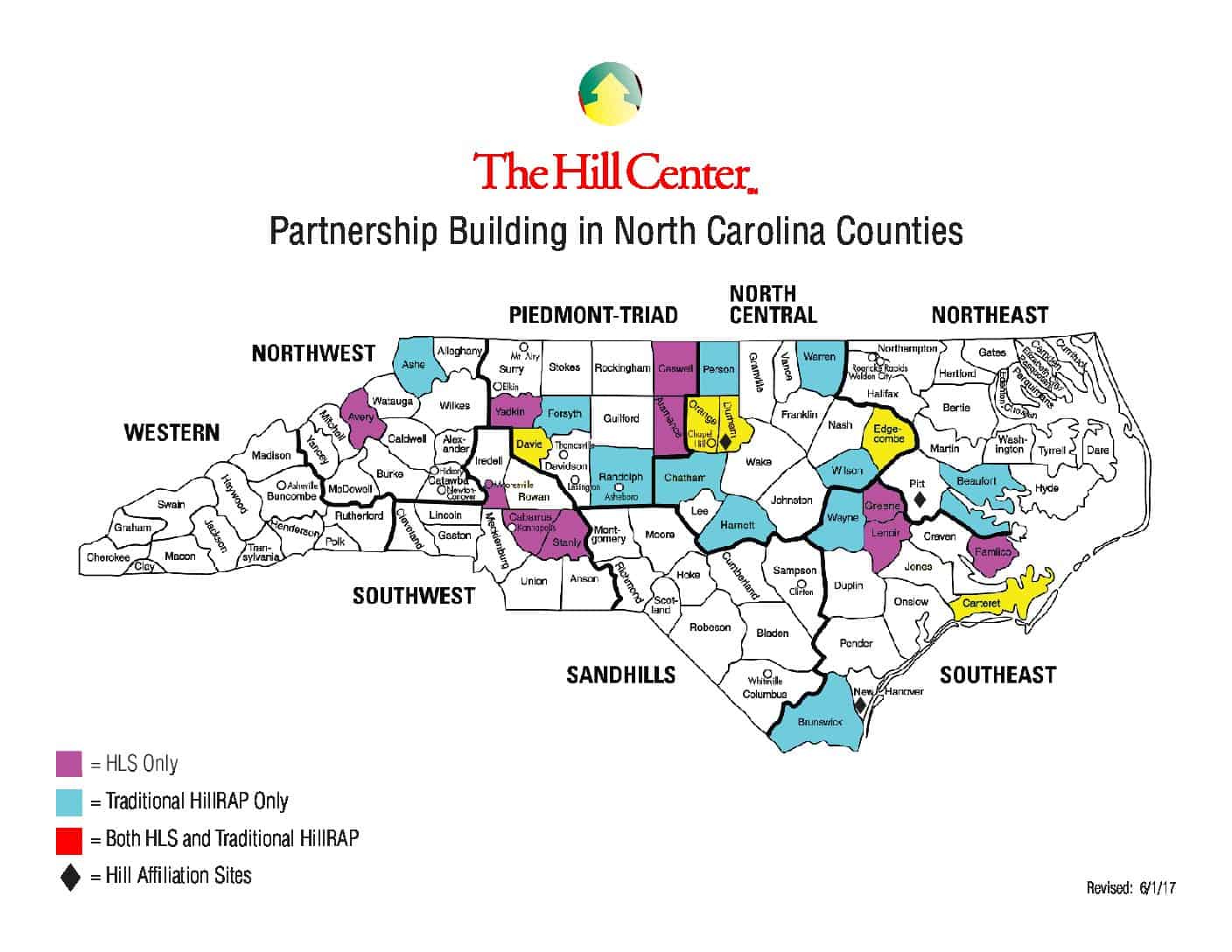

The Hill Center has partnered with 20 school districts in North Carolina for professional development, and hopes to expand to 26 this year, across all eight State Board of Education regional districts.

“One of the barriers to professional development, in general, is that it’s expensive,” said Beth Anderson, the center’s executive director. Hill was founded 40 years ago and provides programming for students, too. Its first partnerships—with Carteret and Davie counties—began more than a decade ago. “It’s common sense, but it is so hard to do.”

Anderson said the organization has been most successful in collaborations with small- and medium sized school systems, which tend to have fewer bureaucratic layers and a shorter institutional distance between the central office and the classroom than large districts. In the best partnership, a system employs a consistent strategy and invests equally among its schools.

But turnover, often driven by North Carolina’s teacher pipeline squeeze, exacerbates the challenges of providing high-quality professional development.

“So many times, you make this investment and then the teacher leaves or the principal leaves or the superintendent leaves and the direction changes,” Anderson said. The Hill Center screens potential participants and tries to seek those who are committed to staying in a district for more than five years. “There is so much turnover, candidly, at all levels,” she said.

Like other professional development programs led by school districts, the state, or teachers themselves, educators who have participated in the Hill Center trainings cite coaching relationships as an important benefit.

“That coaching model is so key,” said Crystal Hill, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction at Cabarrus County Schools. “If that coaching piece is missing, the professional development is really irrelevant.”

Hill is relatively new to Cabarrus County; previously, she directed elementary education in adjacent Mooresville. There, she brought a Hill Center reading camp and teacher training partnership to fruition. She started a similar collaboration in Cabarrus County.

“The best professional development is the kind that you attend and you can go back and implement immediately,” she said.

Indeed, Kerry Blackwelder said she is drawn to the Hill Center model—she has returned every year for follow-up training—because it speaks to her interests in the classroom. “Teachers would be more excited about attending professional development, even spending their own money to go, if it were structured as options to pick from instead of, ‘Here’s where you’re going, here’s what you’re doing, and here’s how long it’s going to last.’”

Despite the glowing reviews from participants, the Hill Center has had to overcome its own funding challenges.

“It is very costly from a human resources and from a financial standpoint to provide professional development,” said Anderson, the executive director. “We’ve had to rethink our financial model.” The goal, she said, is for districts that benefit from Hill Center training to take on a greater share of the cost for professional development.

Private philanthropy has helped underwrite the cost of much of the training Blackwelder has participated in—she sends thank you notes to Hill Center donors after each session. The professional development has been free of charge to her school.

“If that weren’t the case, I don’t know how much professional development I would be getting,” she said. “And that makes me really sad.”