What does rural mean? The word evokes personal definitions. For those who live in settings considered rural, it could mean acres of forest, long drives in between neighbors, or the smell of fresh dirt after harvest season. On the flip side, it could also be described with spotty cell phone service, hand written directions, sparse population, and less connectivity to convenience. Urbanites with little experience in rural areas may have different ideas all together as to what makes a rural community.

Among the nation’s most populous states, “North Carolina has the largest proportion of individuals living in rural areas,” says Rebecca Tippett of Carolina Demography. Our state is second only to Texas in rural population. With people spread far and wide across North Carolina, how does the United Methodist Church manage to serve all its members? One answer is through the Thriving Rural Communities Initiative.

In partnership with The Duke Divinity School, The Duke Endowment, and the two North Carolina United Methodist conferences, the Thriving Rural Communities Initiative offers full scholarships to Duke Divinity students who pledge to serve five years in areas deemed rural by the UMC. Factors determining rural include population, travel time and proximity to a larger city, commuting population, and more.

“The word ‘rural’ in its best sense suggests people of the countryside who live in life-giving relationship with God, with one another, and with the land.” – Thriving Rural Communities

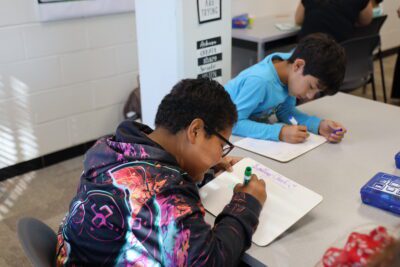

The second week in January, current rural fellows met in Durham to retreat, worship, and discuss topics such as stewardship, cultural humility, and theology. Ismael Ruiz-Millan, director of the Hispanic House of Studies at The Duke Divinity School, joined the group to present on cultural competency and humility.

What is cultural humility? Melanie Tervalon and Jann Murray-Garcia, the authors of Cultural Humility versus Cultural Competence: A critical distinction in defining Physician Training Outcomes in Multicultural Education, describe it as a “life-long learning process which incorporates openness, power-balancing, and critical self-reflection when interacting with people for mutually beneficial partnerships and institutional change.”

In Ruiz-Millan’s presentation, he pointed out the evolution from cultural competency to cultural humility. In seeking cultural competency, one builds an understanding of other cultures with the goal of serving people better. The latter asks that you authentically open yourself to others by being aware of your own bias, prejudice, internal battles, and unresolved trauma.

“We assume because we talk about Jesus loving thy neighbor, then we are culturally humble. But as history proves, assumptions are not necessarily healthy.”

In a 2014 study, the Pew Research Center found 94 percent of the UMC identifies as white. Ruiz-Millan doesn’t shy away from this point; rather, he leans into it, believing it is an opportunity for growth. He said, “[As] United Methodists, we have the saying ‘open minds, open hearts, open doors.’ However, when we look at statistics like the Pew, we realize there is still a lot of work to do to really live it out.”

Understanding and practicing cultural humility can allow an easier “entry point into more complex and controversial conversations that are causing tension and polarization in our midst,” he added. At the end of the presentation, fellows discussed the idea of cultural humility at length and broke into groups to share personal experiences with other cultures that may have been challenging.

There have been 59 total graduates of the Rural Fellows program, with an additional 21 currently matriculating at Duke Divinity School. At the beginning of the retreat, fellows were asked to describe in one word how they feel when they think about the Rural Thriving Communities Program. Around the circle, students chose words such as gift, privilege, and thrive, receiving nods of agreement with encouraging amens.

Recommended reading