As August draws near, public school superintendents across North Carolina are grappling with how to begin the 2020-21 year with plans that keep educators, families, and students safe and engaged in rigorous learning while the country continues to fight COVID-19.

But as superintendents and education leaders piece together the complex logistics that remote and hybrid learning plans demand, their associated costs — ranging from purchasing expensive protective gear for staff, delivering nutrition to students in need in settings outside of school buildings, and investing in computer devices and internet hot spots to distribute to students who cannot access online learning otherwise — are mounting quickly.

And while schools are likely to need significant support and resources in the face of these unforeseen circumstances, school district leaders are staring down another threat that could potentially wreak havoc on their ability to ensure all children are educationally served during this pandemic.

“I think the elephant in the room is the ADM [average daily membership] piece,” said Greene County Schools Superintendent Patrick Miller. “The state provides our budget, or our allotments of money, based on the number of children that they project we will serve each year, and that is rectified between the 20th and 40th days of school.”

“And if we have a significant drop in students who either don’t come back [to school], choose to homeschool, or choose to leave to go to another school of choice, then that significantly affects the budget of the public schools,” Miller said.

Greene County Schools, a small rural school district tucked between Wilson and Greenville in eastern North Carolina, serves just under 3,000 students. Miller says just a 10% drop in enrollment equates to an estimated loss of $2.3 million in state funding, which would arise during the middle of the school year. The consequences would be profound, and result in employee layoffs, moving children to different classrooms, and causing even more instability during a time when children are desperately seeking routine and reassurance. It’s not a recipe for educational success.

What needs to happen? Miller says a hold harmless provision that would prevent districts from seeing steep drops in funding two months into the school year based on ADM counts is necessary — and that is something that only the North Carolina General Assembly can provide.

School budgets at risk thanks to potential enrollment declines

In North Carolina, local school districts receive the lion’s share of their funds from state coffers, unlike in many other states where school funding is drawn largely from local taxes.

The amount of funds a district receives from the state for its schools is calculated based on the average daily membership (ADM) a district is projected to have during the school year. On the 20th and 40th days of school, those ADM projections (sometimes referred to as student attendance, but it’s a bit more complex than that) are reassessed. If ADM figures are lower than what was initially projected, state funds are adjusted by the NC Department of Public Instruction according to certain guidelines.

Typically, student enrollment at public schools across the state fluctuates over time, but rarely do enrollment numbers vary dramatically enough from one year to the next to result in severe budget adjustments just a couple of months into the school year.

But COVID-19 stands to do just that.

“A ten to 20% enrollment drop is certainly a concern around the state,” says North Carolina State Board of Education Vice Chairman Alan Duncan.

While Gov. Cooper announced earlier this month that school districts could elect to implement a hybrid learning option for students this fall (known as plan B) that would consist of a mix of in-person and remote schooling, more than a third of districts across the state serving roughly half of all of North Carolina’s public school students have chosen to begin the school year with all students learning remotely 100% of the time (plan C), citing rising COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations.

As families scramble to come up with their own plans that enable their children to learn while allowing parents to continue to work, local education leaders are concerned that despite offering robust virtual learning options, a significant percentage of families will choose to leave public schools altogether this fall, resulting in devastating budget implications for this year and the years ahead.

“If you have to lose that number of students, whether you use plans A, B, or C — and in particular B, school expenses will still be even greater than a normal school year,” Duncan said.

For in-person instruction, the number of students per classroom must be fewer based on social distance guidelines, the cost of protective gear for staff will be significant, and transportation based on social distance guidelines will also cost more and be logistically complex. And there are costs associated with remote learning as well, said Duncan — even if there are savings in some areas, there are higher costs in others, such as the procurement and distribution of devices and internet hot spots for those who do not have broadband access and the distribution of child nutrition.

There has been some financial help for schools to mitigate the sudden costs associated with the pandemic. Congress appropriated federal COVID relief funding to states earlier this year with the passage of the CARES Act, and the North Carolina General Assembly has, so far, distributed nearly $400 million of CARES funding to K-12 public schools.

For Greene County, those funds have helped, to some extent.

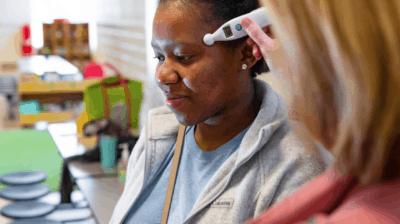

“The state has provided two months’ worth of PPE (personal protective equipment) for school nurses and those on the front lines of screening students,” Miller said. But the school year is 10 months, he said, and initial PPE costs are already very high. $15,000 for three weeks’ worth of hand sanitizer. $17,000 for an initial mask order. Disposable gowns that are intended for one time use are $4 each. There will be higher personnel costs to screen students, and other needs related to providing students with devices and internet connectivity, school buses, transportation, and substitute teachers.

Miller has access to nearly $1.5 million in federal aid appropriated by the General Assembly so far, according to the NC Department of Public Instruction. Enrollment dips amounting to a $2.3 million budget reduction, however, could quickly wipe out that aid.

ADM hold harmless provision necessary to keep districts afloat

Jack Hoke, Executive Director of the North Carolina School Superintendents’ Association, says the legislature has to act to hold school budgets harmless for 2020-21, agreeing with Miller’s assessment that enrollment drops are on the horizon. “It’s very possible we will see anywhere from 15 to 20% loss in students this upcoming year,” Hoke said.

The sudden costs associated with mitigating an infectious disease for which there is no vaccine or reliable treatment methods yet, as well as the shock of school budgets taking hits thanks to unexpected enrollment dips is a lot to handle. But that must also be considered in the context of a couple other significant realities — first, many school districts across the state still haven’t recovered from the effects of the Great Recession that took place now more than a decade ago, along with significant tax cuts that decreased revenues available for public education. In FY19, per-pupil spending remained 6.2% below pre-recession levels in districts with the highest levels of school-aged poverty, according to an analysis by the North Carolina Justice Center.

To cope with state-level disinvestment that has eroded budgets over the past decade, local districts have raided their savings, or fund balances, to make up the difference. An analysis by EdNC found that overall, fund balances across North Carolina are lower than they were before the Great Recession — and that’s important because these savings enable local districts to make critical decisions around school planning when the General Assembly may be tied up passing a budget, something the state is dealing with now.

Second, North Carolina’s courts — as well as an independent consultant — have found that the state continues to fail its constitutional obligation to ensure every child has access to a sound basic education, and has done so for at least the last 20 years, since the beginning of the Leandro litigation. A lack of investment in resources and funding for public schools, especially in schools and districts serving North Carolina’s most vulnerable populations, is to blame.

“Our Leandro children who struggle in low socioeconomic conditions have suffered significant academic losses — and we must act to mitigate the losses they stand to see even more of this year,” said the State Board of Education’s Alan Duncan. Remote learning plans demand access to reliable broadband internet, something that many North Carolinians don’t have access to thanks to poor infrastructure or prohibitively high costs. Nearly 200,000 households across the state lack access to broadband, according to the NC Department of Information Technology.

The pandemic has laid bare these stark inequities, and rural districts are on track to struggle even more than they currently are. Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union, says he believes it’s the intention of the North Carolina General Assembly to take up the idea of holding school budgets harmless if they experience ADM drops this fall.

“That’s the desire,” Rep. Horn said. “Ten percent [in budget reductions] is a lot of money — and no, districts can’t handle that kind of reduction.

“It’s the intent of the General Assembly, I think, to hold budgets harmless. But I can’t guarantee that will come to pass — my crystal ball doesn’t work so well.”

The funds for school budgets for 2020-21 have already been appropriated by the General Assembly, so a measure to hold budgets harmless wouldn’t require a new appropriation. And, said Horn, there remains additional CARES Act money to be spent — along with the hope that Congress will appropriate even more stimulus money this fall.

In the meantime, Rep. Horn acknowledged, there’s little that superintendents can do on their own to staunch the potential bleeding of their budgets.

“The fact is — the state provides the great bulk of funding for public education,” Rep. Horn said. “So there are few alternative resources available of any great extent to public schools. Certainly the General Assembly doesn’t want to be put over a barrel here, and the schools don’t want that, either.”

Horn noted that before adjourning, the House did pass additional COVID relief measures — but the Senate did not take them up. Recently, Senate leader Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, published a statement urging families to consider using a taxpayer-funded voucher program to leave the public schools and attend private schools, which are more likely at this time to be open to in-person instruction.

“I’m going to give Senator Berger the benefit of the doubt,” Horn said. “I will suggest that [with his statement] he is highlighting that there are options for students.”

“But I will also hope that Senator Berger will continue to support traditional public schools as the basis of the state’s education plan,” Horn added. “Traditional public schools, for me, are the backbone of education — not only for this state, but for the country.”

Editor’s note: This piece was originally published by the Public School Forum of North Carolina. It has been posted with the author’s permission.