The State Board of Education’s monthly meeting began with a reminder of the challenges facing teacher recruitment and development. Thomas Tomberlin, the Department of Public Instruction’s director of educator recruitment and support, included a few issues in his update over which the Board voiced concern:

- Continued decline in teacher output from educator preparation programs.

- Persistent decline in licensure exam pass rates.

- Funding cuts to regional support for teachers.

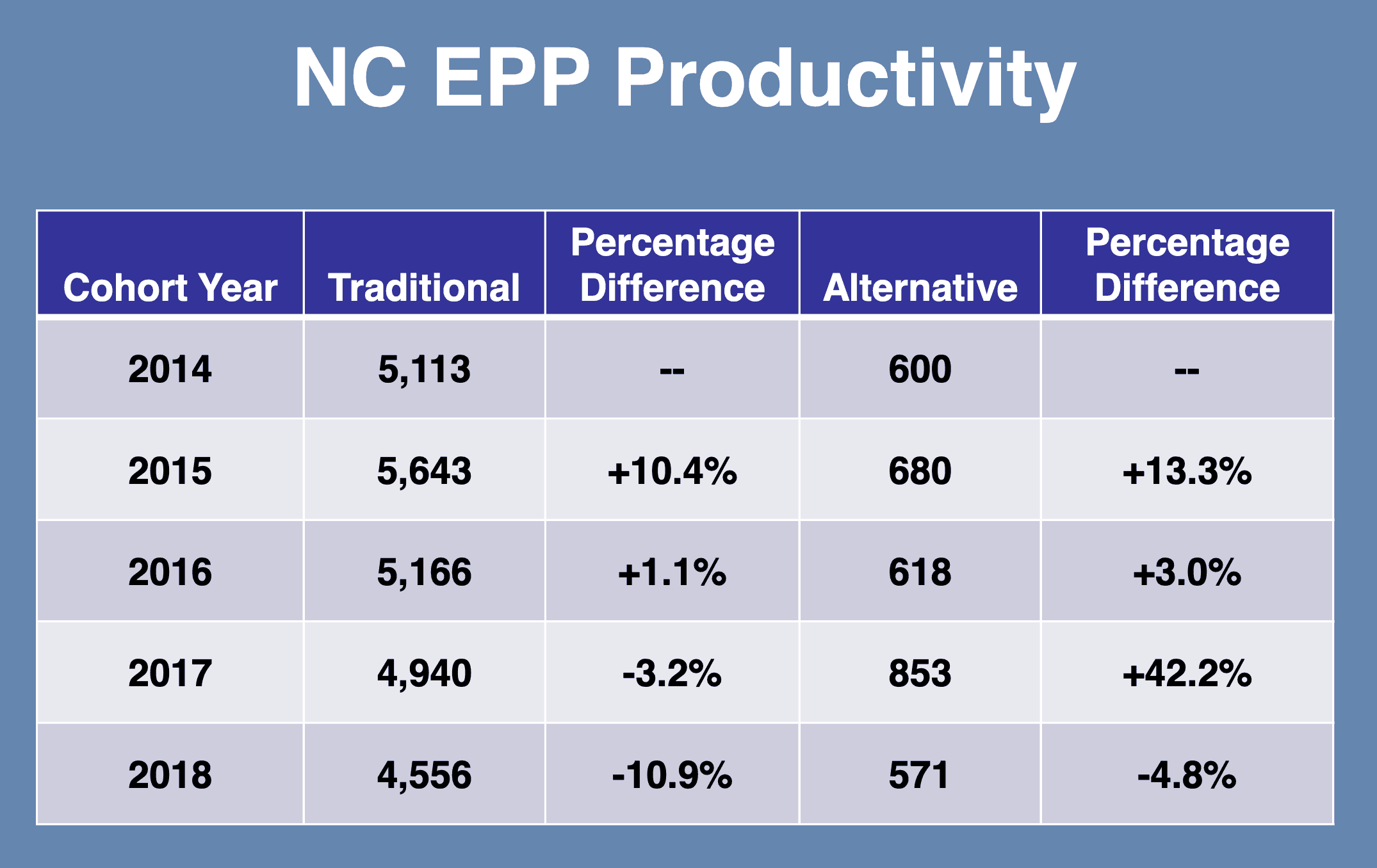

Each of the two routes to becoming a teacher in North Carolina continued to stutter in producing classroom professionals, end-of-year data from 2018 showed. For graduates of education prep colleges in North Carolina, teacher output declined for the third consecutive year – down almost 11% from 2014. For lateral entries with ties to state education prep programs, the output declined in 2018 for the first time in four years, down almost 5% from 2014.

Tomberlin said, however, that he believes the pipeline is strong overall.

“There’s some bumps from year-to-year,” he said, “but in the end it’s kind of a wash between 2014 and 2018. … We know that enrollment is down somewhat, but it does seem like there is some stability in that pipeline from our ed prep programs.”

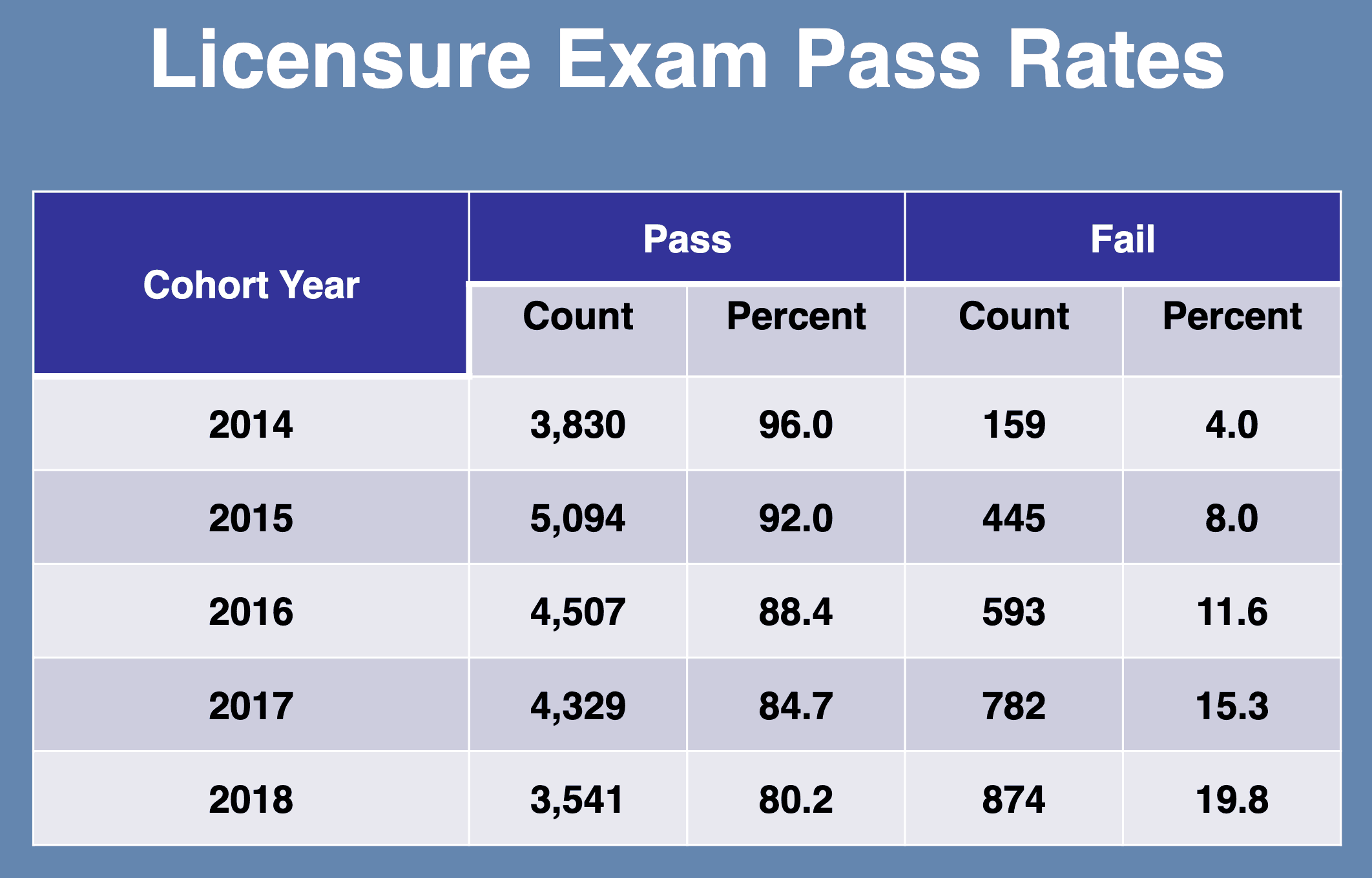

Of more concern to the Board was the licensure exam pass rate, which has declined by roughly 4% in each of the past five years, dropping from 96% in 2014 to 80% last year.

“At that current trend, is there any reason to believe that we have hit bottom,” Board member Matthew Bristow-Smith said. “Or five years from now, will we have a 60% passage rate if current conditions that have created this reduction don’t change.”

Tomberlin pointed to a couple of factors contributing to the low pass rate. He noted that when the state saw 96% in 2014, it was under old legislation that required every graduate to pass the licensure exam prior to entering a classroom. Starting in 2016, graduates have three years to pass the exam. As such, some portion of the 20% who did not pass in 2018 knew they had one or more opportunities in later years to pass the test.

“This is not really an accurate way to measure the pass rate,” Tomberlin said. “If we are going to give those teachers the opportunity to forgo passing the test until two or three years after they complete their programs, then we should measure their pass rates as a cohort and measure the pass rates at the end of that three-year term. That’s what we’ll start to do going forward.”

Tomberlin did say the decline from 2016 to 2018 is statistically significant, adding that he believes it is “practically significant.”

“Something’s happening there,” he said. “My first guess at what’s happening is not a serious and rapid decline in the quality of our ed prep programs across the state. I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think what we’re seeing here is about the percentage of people who enter the teaching profession who are procrastinators versus who are somebody who likes to get the difficult things done up front. So we have 20% of people who are saying, ‘If I can wait for three years, I’m going to wait for three years.’”

Board member JB Buxton posited that if the state required teachers to pass a licensure exam prior to going into classrooms, there would be time to fix any deficiencies in content instruction prior to putting a teacher in front students. Board member Amy White worried about 20% of the teachers having not passed the licensure exam being in classrooms, particularly in hard-to-fill vacancies which tend to be in low-performing districts.

Tomberlin responded, however, that failure to pass the licensure exam does not necessarily mean that teacher is not qualified. He added that data suggests there is no difference between a teacher who passes the test in the first year and one who passes in the third.

“The problem I’m having is equating not having passed the content licensure exam with not [being] adequately prepared,” Tomberlin said. “I don’t think that I can make that jump. It is clear: we are sending more teachers into the classroom who have not passed their content licensure exam than we ever have in the past. And that is a significant number of teachers. Whether that means they’re not as well prepared or not, I don’t think I have the evidence to support that.”

Tomberlin added that low-wealth districts with the lowest-performing schools may not benefit from keeping ed prep graduates who have not passed their licensure exam out of the classroom – particularly when the alternative, in light of many vacancies, is long-term substitute teachers filling those classrooms.

“Aren’t those teachers who have been through an ed prep program and not passed the test better than the long-term sub that we’re prepared to put in those classrooms because we have no one else?” he asked. “… That’s the pushback I get on any of these licensure policies that we put forward.”

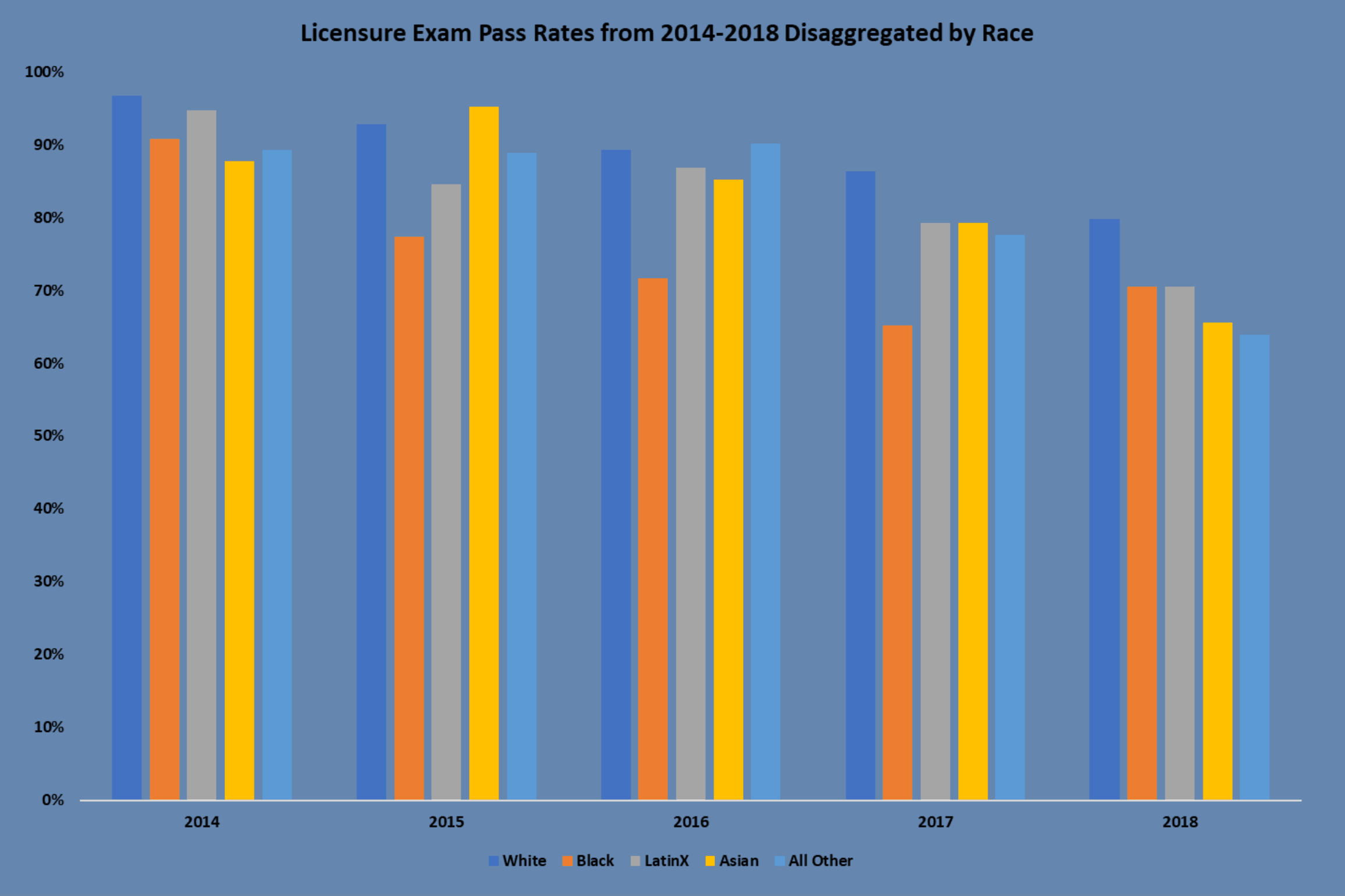

In analyzing its 2018 year-end data, DPI for the first time disaggregated it by race. This shows a lower passage rate for black and LatinX students.

“There is a discrepancy,” Tomberlin said, adding, “I don’t have a ready explanation for this. Right now, I just know this exists.”

Finally, Tomberlin discussed changes to the support model for ed prep programs seeking national accreditation. For instance, face-to-face support was previously available for general individualized and regional support, as well as trainings, professional development, workshops and community session. Staffing and funding constraints have led to a push to offer these through virtual support.

This is a shift the Board was not happy to hear.

“There is not another time that we need to support EPPs more than now,” Board chair Eric Davis said. “We reject the new support model. We want the old support model.”

On Thursday, Board member Olivia Oxendine made a motion, requiring DPI to provide the previous level of support “such that our ed prep programs receive systematic assistance as they pursue national accreditation.”