It wasn’t that long ago that a person graduating from a North Carolina high school could walk out in their cap and gown, smiling at their waiting family members, and know a good living-wage job was waiting for them.

There was no urgency to a college degree. There was no rush to get a postsecondary certificate or credential.

In many cases, there was even no need to leave one’s own hometown to find a middle-class career.

Those days are gone now and the thought of finding a job that could support a family with only a high school diploma seems quaint.

Earlier this month, Durham-based nonprofit MDC, in partnership with Charlotte’s John M. Belk Endowment, released a report detailing a troubling trend across North Carolina: more and more children born into low-income families are staying there.

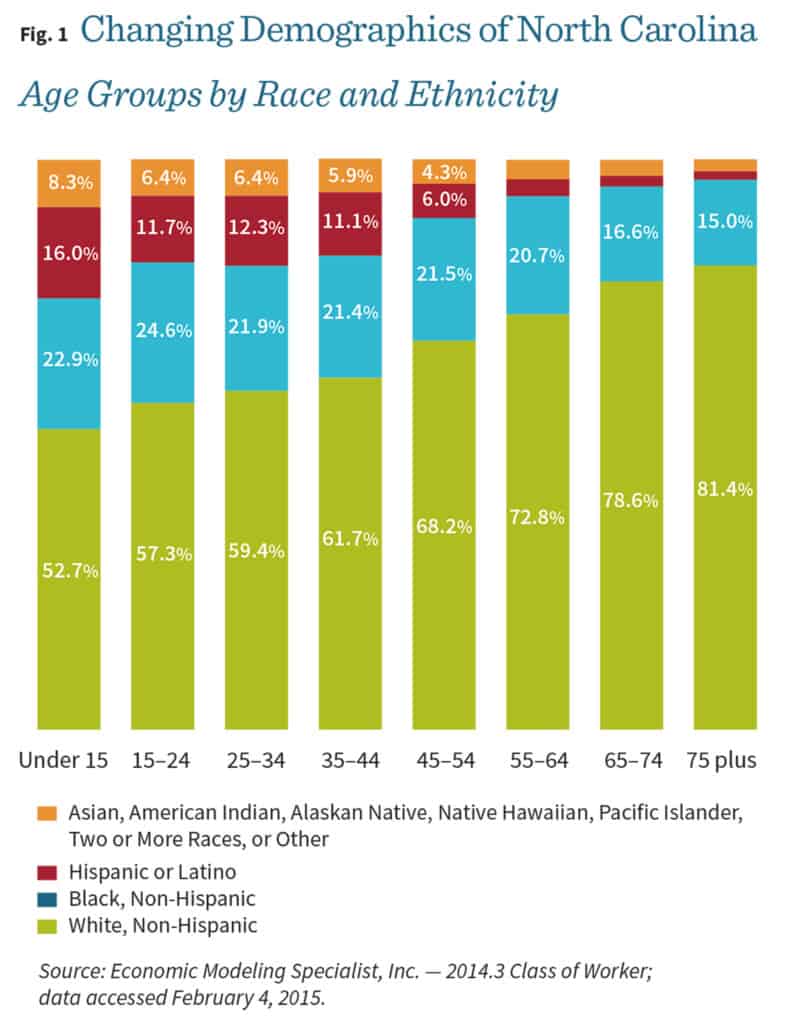

The report, titled “North Carolina’s Economic Imperative: Building an Infrastructure of Opportunity,” examined state-wide data on demographics, economics, and job growth. Some of the data we’ve heard before. The state is increasingly becoming more diverse with Hispanics and African Americans accounting for larger percentages of the population, particularly those 45 and under.

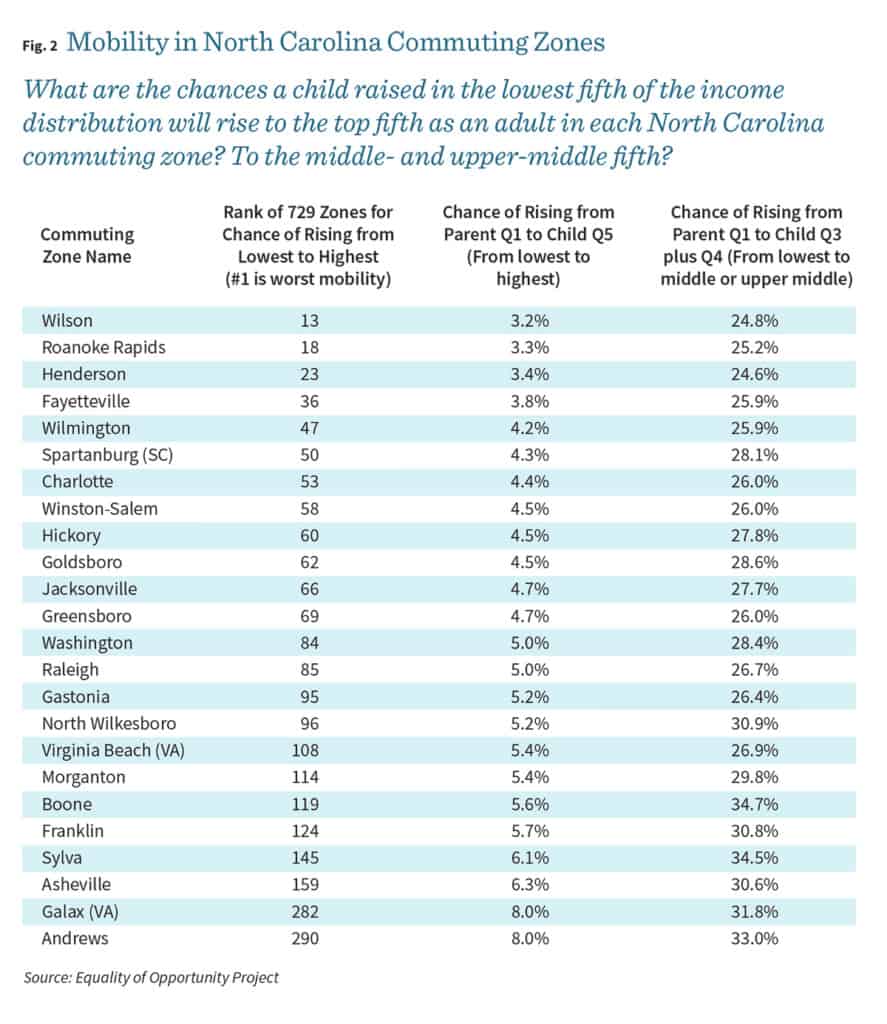

But some of the data presented is surprising and a bit disheartening. Throughout North Carolina, regardless of whether it is a metro area or a rural community, economic mobility is becoming increasingly out of reach for many. Children born today are more likely to live the life their parents lived, to achieve the same level of education, and to have a comparable level of economic security. And they in turn will be less likely to provide a better life for their own children.

In Wilson, for example, the report notes that of children born into the lowest income quintile – households earning $19,916 or less – only 25 percent have a chance of moving into either the middle ($36,752 to $58,159) or upper middle ($58,160 to $93,418) income quintiles. And only 3 percent are likely to move into the highest income quintile, a household income of $93,419 or more.

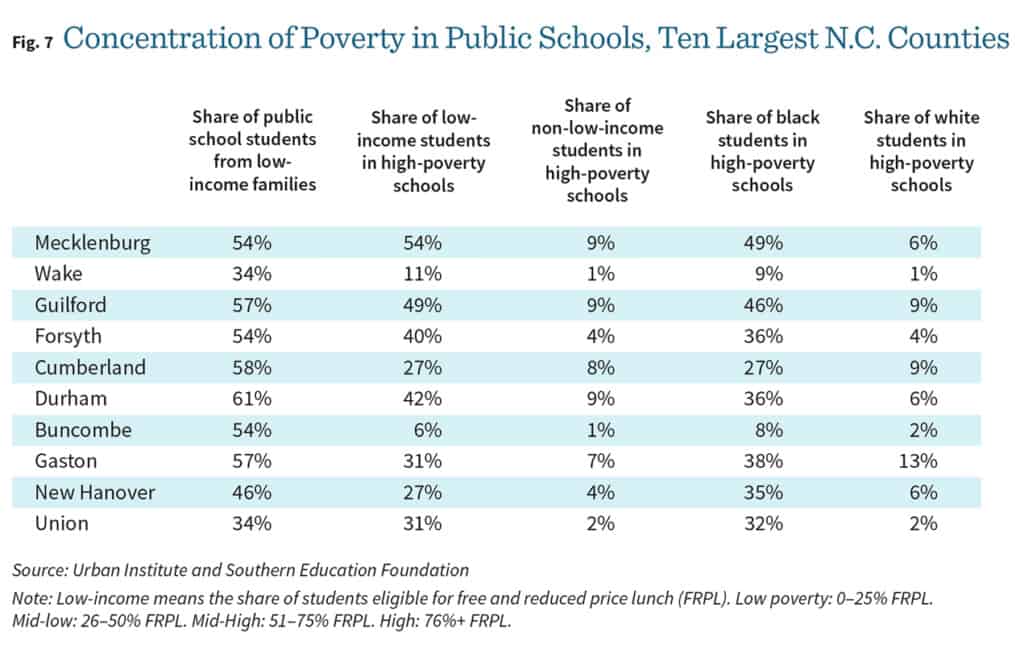

The report cites school poverty and segregation as one of interconnected factors that stymie economic mobility. The authors note that “… in many places, educational quality varies widely between schools and between districts, and residential segregation and school funding formulas often concentrate students from low-wealth families in lower quality schools.” And too often, it is families of color that end up populating those neighborhoods and whose children end up attending those high-poverty schools.

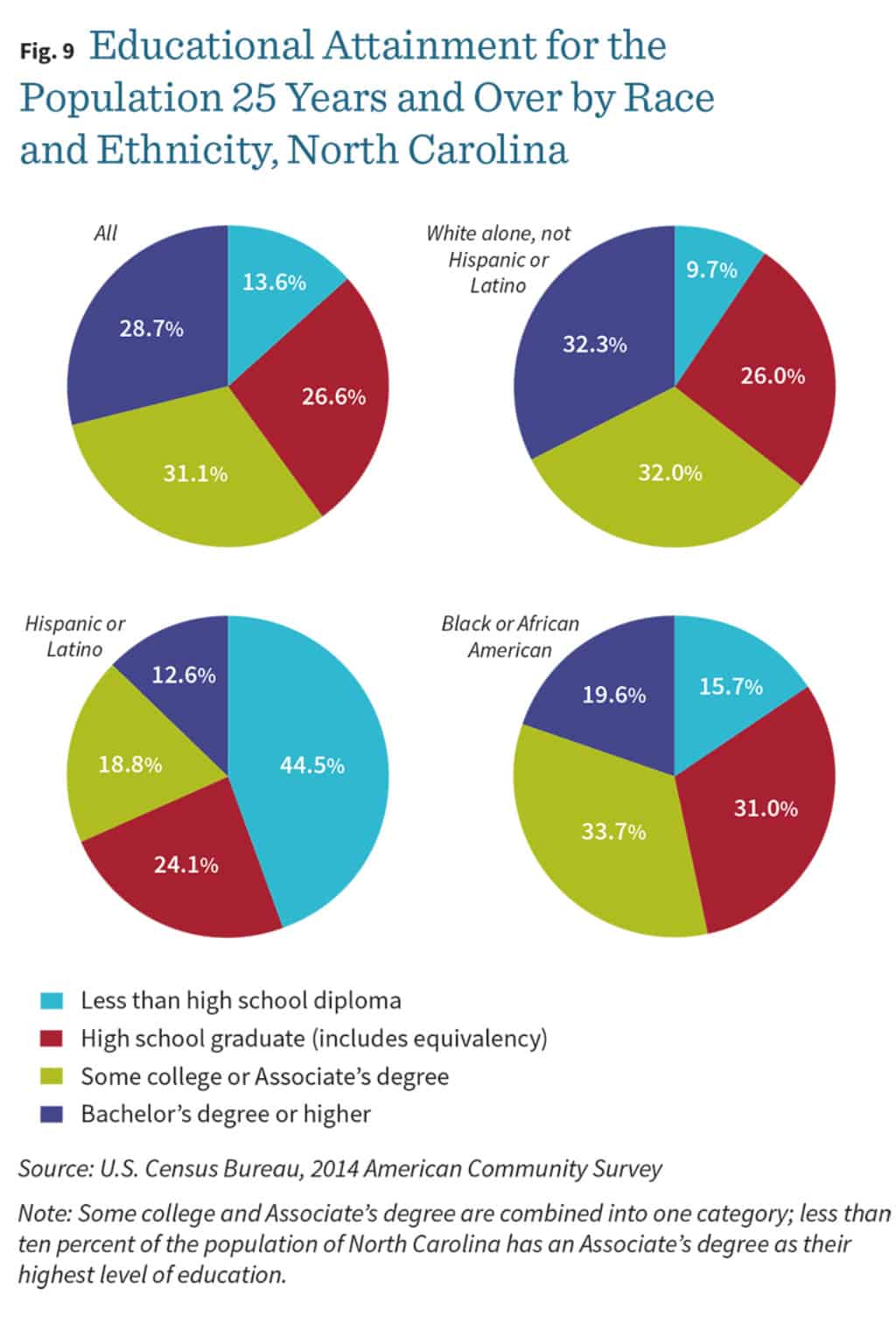

Education is key to giving a child the chance to move up into a higher income quintile and create a better life than his or her parents had. But as the report notes, “educational attainment is deeply tied to family income,” meaning children born into a low-income family or to parents without postsecondary education are less likely to attain education beyond what their parents attained.

It’s a brutal cycle, and one that is economically problematic for a state that is becoming increasingly diverse, and which will become more and more reliant on a workforce made up of higher percentages of Hispanics, Asians, and African Americans.

Just under 13 percent of Hispanics have a bachelor’s degree in North Carolina and just under 20 percent of African Americans do. That’s compared to 32 percent of whites.

Nearly 69 percent of Hispanics have only a high school diploma or less. That’s compared to 47 percent of African Americans and just under 36 percent of whites.

The MDC and Belk report digs deeper into state- and regional-level workforce projections, and what education a worker would need to fill those positions.

The message is clear:

The jobs of tomorrow, the jobs that will be available to the K-12 students of today, will require a higher level of educational attainment but will provide a better chance at economic advancement and security.

Education now plays out along a life-long continuum of learning and training, one that starts during pregnancy and continues throughout an adult’s working life. It requires supports outside of the classroom that will help a student be academically successful, and it must continue in conversation with businesses and industry to identify the skills needed to fill the jobs of tomorrow. As the report notes, “A strong education-to-career continuum connects more people to the necessary postsecondary credentials and family-supporting employment needed for individuals, their communities and the state to thrive.”

As part of the report’s launch, EdNC featured profiles of six North Carolina communities working to improve opportunities for their youth and young adults.

Places where education and industry are working together, along with community leaders and elected officials, to increase economic mobility and help their communities thrive.

Cultivating aspirations: Vance, Granville, Franklin, and Warren Counties

Partners at the speed of trust: Guilford County

Recovery through collaboration: Wilkes County