Nevaeh Simpson has a generous smile, the ear-to-ear kind that lights up a room. The ninth grader at North Shelby School wears it often, even during these tense and confusing times.

“She doesn’t look at life like we do, like we always want it to be different or better,” says Brandy Woods, Nevaeh’s mom. “She’s always happy with anything that you give her — the littlest things. And she brings so much joy, regardless of her disability.”

Nevaeh’s got a list of diagnoses – from cerebral palsy to ADHD. She’s non-verbal and needs help improving her motor skills. Her individualized education goals include learning some basic life and vocational skills that will one day allow her to live and thrive on her own. For that, she relies on services through Cleveland County Schools’ Exceptional Children (EC) program.

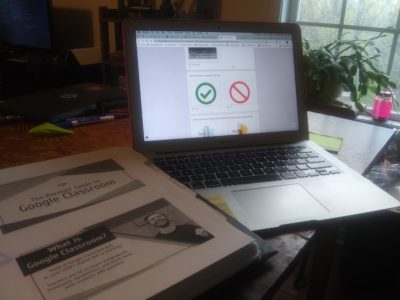

When school buildings closed, fear crept in for Nevaeh’s mom. The services her daughter receives are in-person and hands-on. How could they possibly continue from afar? And if service stopped, how much would Nevaeh fall behind? Very quickly, though, Woods found an unexpected ray of light.

“We’re online. It’s the best we can do right now, but one of the reasons why COVID-19 has been a blessing in disguise is I’m getting to really see the techniques that the teachers are using,” Woods said. “In the past, I relied more on the teachers to do it rather than doing it so much at home. Now, this learning has helped me see a better way to try to communicate and help her learn. It’s going to be better in the long run.”

The blessing is a byproduct of intentional guidance from Cleveland County Schools’ Exceptional Children Department. Under the leadership of its director, Nellie Aspel, the department acted quickly to implement a remote learning plan for EC kids that prioritizes communication and connections with parents. Just two weeks into remote instruction, it’s helped deepen relationships and reveal the power of communication between teachers and parents.

Behind the Story

This is the second piece of a two-part report on how the move to remote learning is affecting Exceptional Children. This story focuses on what remote learning for EC teachers and parents looks like in Cleveland County Schools, including some hidden blessings among the challenges. In the first piece, we explored state issues and guidance.

Forming bonds and understanding

Communication is not a new priority for the district, but the level and commitment to it have, by necessity, sharpened. With remote learning, some services cannot be provided. Some Individualized Education Plan (IEP) goals will fall by the wayside, and students across the state will unfortunately lose gains and face a lot of catching up. Amid all this, though, the necessity for over-communicating has brought parents and EC teachers closer.

The first directive from the district’s EC department was that each teacher contact the families of their students. The purpose was to communicate the plan, check if families had basic needs met, and inquire about internet access. Often, the calls moved beyond their original intent — into a shared grieving over coronavirus and closed school buildings.

“At Christmas break and at Easter break and summer break, all those breaks, we know they’re coming and so we’re able to say our goodbyes,” said Jessica Yarboro, a speech therapist at Fallstone Elementary School. “But with this, at least in our county, we were in school on Friday and then on Saturday we got an email saying we’re not going back. We didn’t get to say our goodbyes and now it’s up in the air if we will go back to school this year. That’s been hard on all of us.”

As they bonded over common struggles and frustrations, teachers invited parents who are able – those who aren’t working or could manage the time outside of work – to sit with their kids during remote instruction. At first, it was an exercise in observation. Soon, though, parents became amazed at what they saw.

“Watching parents sit back and go, ‘Oh, I didn’t know he could do that or I didn’t know she knew that,’” said Shi Whisnant, an EC teacher at North Shelby School. “That’s the part that’s been amazing. It just opens up a new window and a new view for them of their kids.”

It’s opened the eyes of teachers, too, who now log on and get to watch their students’ home lives happen in the background. Before and after lessons, teachers talk to parents. They listen to parents’ concerns about their child’s services. And they listen to the parents’ concerns about life, about work, and about the struggle for new balance.

“I definitely think there’s a deeper understanding on all sides, my side as well as the parent,” said Jenny Harrill, an EC teacher at Union Elementary School.

Understanding is indispensable between teachers and parents of Exceptional Children. One article tracing the roots of special education in America noted that it “is a framework where the foundation is built on adversarial relations — where parents hire attorneys and advocates to fight against districts.” But breaking free of that conflict and forging partnerships between parent and teacher may mean better outcomes for students.

Those partnerships aren’t universally found across the state, or the nation for that matter. In Cleveland County, though, the coronavirus school year is providing an opportunity for fostering collaboration.

Class sizes double as teachers coach parents on instructing kids

Nevaeh Simpson. Photo courtesy of Brandy Woods.

Learning still has to happen, and oftentimes that requires a hands-on approach that simply can’t be done through a computer screen. In those cases, Cleveland County’s EC teachers have become coaches, and some parents have become instructors.

“The parents are also having to be a teacher now,” Harrill said. “And we’re guiding them on how to do that. Even though parents sit in on IEP meetings, and we develop that plan together, now they’re trying to see how to implement that plan. And I think that they are understanding more of what all goes into that. And we’re able to help better communicate what we ultimately want as our goal and how to deliver that instruction on a daily basis.”

It’s more work for the parents, and it’s also an extra seat in the classroom for teachers. They’re reviewing and modeling lessons for their students, and then they coach parents on how to practice at home.

For her part, Woods has enjoyed the coaching. She comes home from work in the evenings and she’s tired. But she knows she won’t be there to care for Nevaeh forever. Her voice sounds equal parts anxious and impassioned as she talks about a day Nevaeh can care for herself and live on her own. It’s hard and exhausting, but after work she sits straight down at the table to teach Nevaeh. And in those moments, she’s grateful for the coaching she’s received from Whisnant.

“As a mom, I never got to stay in class with her and see the things that these teachers are teaching,” Woods said. “It’s definitely eye-opening for me.”

And helping to provide instruction has brought her closer to her daughter.

“She’s happy,” Woods said. “If you know my daughter, she’s smiling. She’s a diva. She’s like any other teenage girl who has her moments. She gets frustrated because she can’t speak. But she’s amazing. She never gives up. She’s determined. And so that’s why I’m thankful for this, because it’s helping me learn more for her. It’s helping to bring us even closer.”

Whisnant teaches lots of kids with significant cognitive disabilities, many in transition classrooms. She works with them on math, science, and reading — as well as things like daily living skills and vocational skills.

“Sometimes my role in a call is to coach a parent on how to do hand-over-hand or how to model the different levels of prompting and how to set up a daily schedule or a visual schedule,” Whisnant said. “I want them to have every possible resource that I can get them to make this less frustrating. But it’s really changed our roles a bit where they become the hands-on teacher and we’re the voice coming out of the computer or over the phone, walking them through and getting their feedback.”

Sharing these resources and modeling instruction has meant more consistency for students, who now see the same strategies from their teachers and parents.

A similar parent-coaching approach has worked in core curriculum instruction. Nicole Olsen is an EC teacher at Burns Middle School, supporting English Language Arts students. Her kids mostly need support in writing, reading fluency, and comprehension. Her students are striving to read and write at grade level.

At school, Olsen uses a program called Xtreme Reading, which helps, for instance, with word identification strategies for reading fluency. Parents can now see the reading strategies she uses with their kids. They watch as Olsen uses Reading Rockets’ Reader’s Theater. And they notice when certain strategies click for their children.

“The opportunity for coaching with the parents has been great,” Olsen said. “It’s amazing because the kids are learning, but you can see it happening for the parents, too. And my parents are being really supportive. I’ve spoken to every single one of them and they’re thanking me for what we’re doing and that we’re still providing new learning to their students. We’re here to support them throughout the day and they know that, so they’re very appreciative.”

Building relationships to last beyond shelter-in-place

It’s not a perfect situation. Many parents are working and can’t be both provider and teacher. Some don’t have internet access, making engagement more difficult. Others, try as they might, can’t perform certain services at home.

But even in those situations, the increased communication has helped forge relationships that could pay dividends down the line.

“I don’t think it’s worked perfectly in every situation, but I do feel like I’ve grown a lot in my relationships with all the parents and students that I serve,” Harrill said. “We’re still trying to work out the kinks with the parents that are working and the children who are trying to do this at night or after their parents get home, or with older siblings or whoever’s taking care of the children during the day. There’s a learning curve for all of us trying to figure out how to make this work.”

Already too much is asked of some parents, who are balancing work with having kids home from school. EC teachers in the district relay stories they’ve heard about bills piling up and how much harder things are with social distancing. Hearing the teachers talk about it, you get the feeling they want to crawl through the computer screen and give the families a hug. They know, even if they somehow manage to get through the monitor, they’d have to stay six feet back nonetheless. So they do what they can. They listen.

“If anything, one of the best things that’s come out of this whole experience is the relationships that we’ve had with our families have become stronger, become more intimate, for lack of a better word,” Whisnant said. “I think we’re definitely going to see things from our students we’ve never seen before. And I think our families are going to see things from their teachers that they’ve never seen before.”