In a school designed to teach students to take ownership over their future, the first graduating class at Montgomery County Early College (MCEC) have gone beyond that — helping also to establish the school’s culture and start new traditions.

“Our students have just gone out and made themselves a part of this campus,” MCEC principal Heather Seawell said. “It’s a college and it’s a high school, but our students aren’t just tucked away in their own space. It’s a community, and they make themselves very much a part of it.”

A school culture built by students

When MCEC was established on the campus of Montgomery Community College in 2016, enrollment consisted of 126 freshmen and sophomores. The only ones who had any experience with a traditional high school were the 60 sophomores.

“At a traditional high school, you push your kids to graduate,” said English teacher Heather Beane. “But our kids are having to step up to another level, really, from day one. And they’re having to fill some really big shoes. And they set their own goals. They’ll come to us and say, we want to do this, this, this, and this.”

There were a lot of this, this, this, and this’s.

The second week of school, they were already asking when they could have a student government. That first semester, they were asking about school dances and clubs. The sophomores had gotten a taste of typical high school life and wondered if they could preserve those high school experiences while still chasing a college degree.

“It’s built, but it’s because the kids wanted all these things,” Seawell said. “It’s a family atmosphere where they have a voice in what happens.”

They asked for and got a fall dance. Last year they held their first prom. They established clubs, which are in addition to the college clubs students are eligible to join. The Beta club, a student-led group that competes statewide and nationally, placed second in the nation at a recent competition.

“The key is that the students do so much,” math teacher April Daywalt said. “The students take charge.”

But while they were building a high school together, the students were at the same time setting out on a college journey. At most of North Carolina’s early colleges, the curriculum is designed to allow students to earn both a high school diploma and an associate degree in four or five years.

“When you walk in, college is already on the table,” Daywalt said. “It’s not something that’s four years off in the future.”

The first group of sophomores, however, were already a year behind on a fast track. They had to spend time in college courses almost immediately, getting their bearings in harder courses with a greater emphasis on independence and higher expectations for top grades.

“They were in this position where they had a taste of what high school was like,” Seawell said. “Then they entered early college, and it was different. There were many students that first semester who kept talking about going back.”

They talked to teachers and advisors about the heavy work load. Some were worried they were not making straight A’s.

“Okay, but let’s be honest,” Beane would tell them. “You’re in seven classes. If you were in another high school, you’d be in four. So what if you have two B’s in college classes. You’re still way ahead.”

By year’s end, only one had transferred back to their traditional public school. And of the 59 who stayed, all are graduating with high school diplomas, 42 are graduating with college diplomas, and 14 are enrolled for a super senior year to get their associate degree.

Not only does their example serve as inspiration for the classes behind them, but the students have taken a proactive approach to helping younger students with the transition from middle school to college.

A little help from their friends

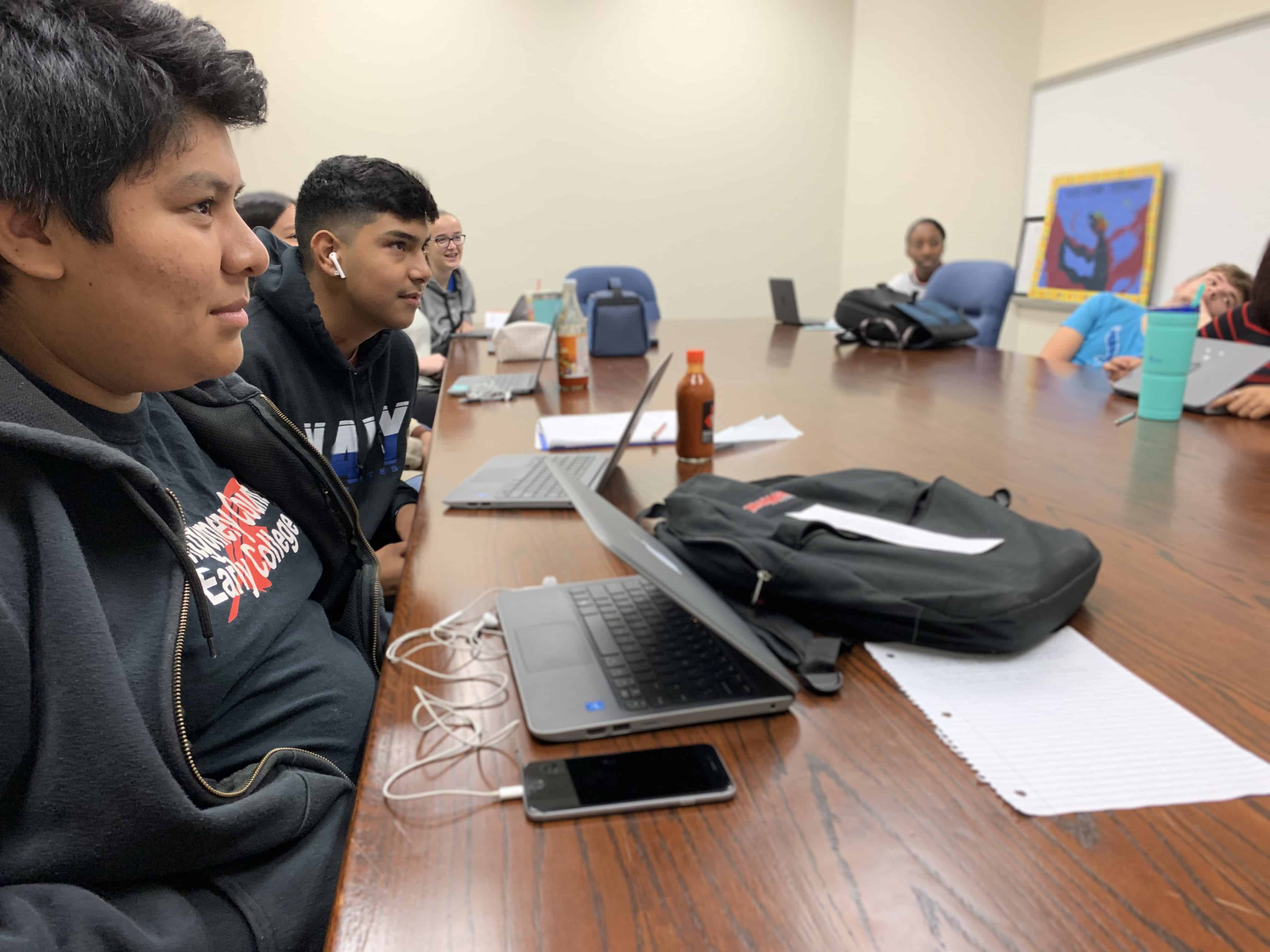

As you walk the halls at MCEC, you see students congregated — at tables outside classrooms, in a game room on the college campus, and stopped in the halls talking with each other.

In classes, they are grouped within cohorts of same-grade students. Outside of class, though, they mix. Seawell says it’s a testament to the upperclassmen, who make it a point to know the younger students, help them with the transition, and encourage them to participate in clubs and events.

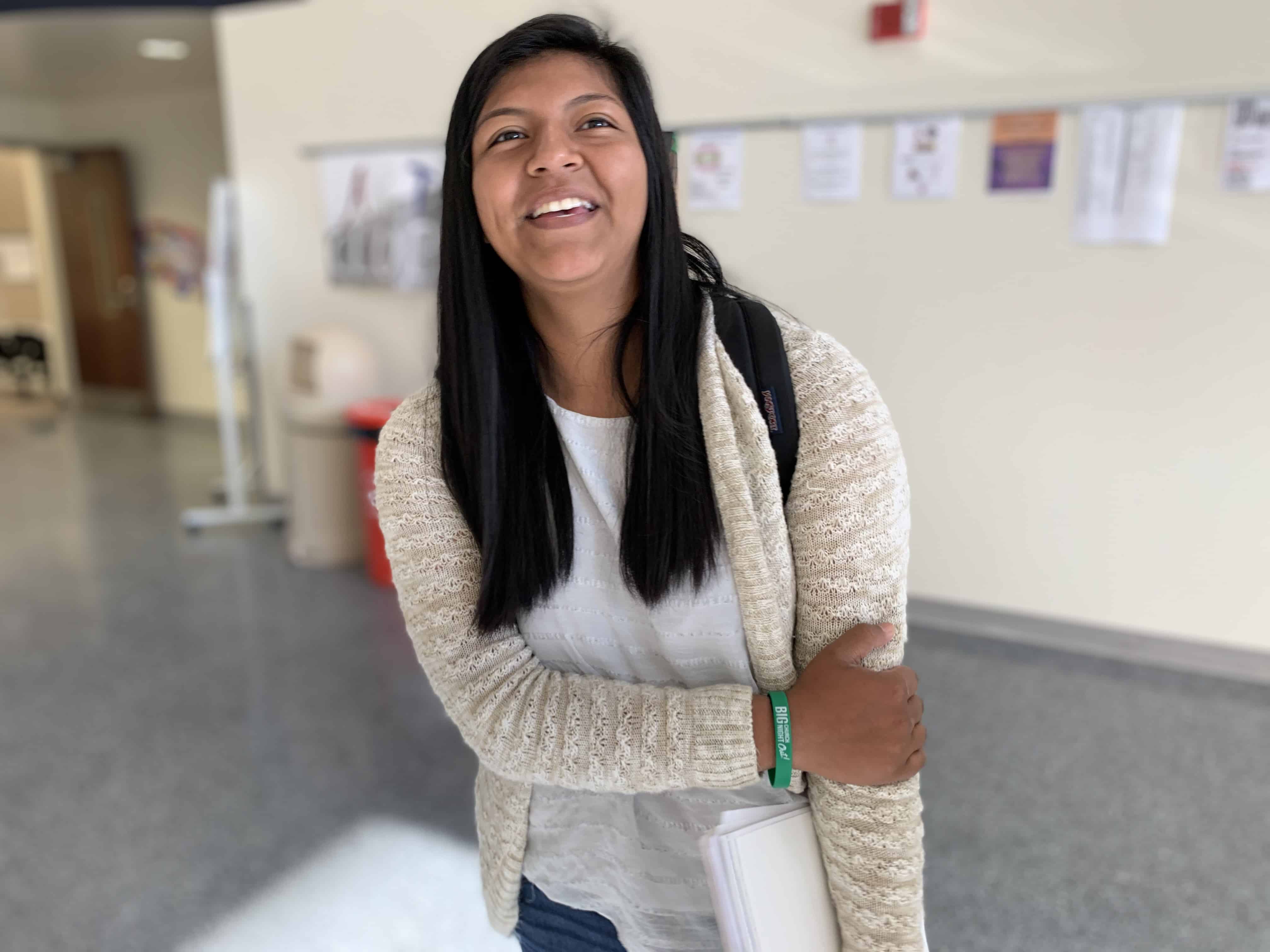

“Everybody knows each other, so if someone’s struggling everybody knows what they need help with and that they can count on people here,” said Abigail Cristobal Salgado, a graduating senior and president of the student government. “It’s easier for us to go up to someone and say, ‘Hi. How are you?’ Or you can just sit with someone without them thinking you’re weird or anything like that.”

Just recently Salgado had two freshmen come and sit with her. She talked to them about how their classes are going and their fears.

“They’re going from middle school to college, and they were scared,” Salgado said. “But they know now they have us to talk to. And I’ll just walk down the hall, and they’ll say hi. They already feel comfortable and know that they have that support from us [seniors].”

How do you build a culture like that?

“It’s intentionally how we built our schedule and how we do things,” Seawell said. “We assigned students to cohorts. So they’re in a cohort of students who come in together and stay together freshmen and sophomore year. And they get to really, truly understand each other and know each other and depend on each other.”

The school focuses on team building in homerooms, and they pair seniors with freshmen in a mentoring program.

“There’s only 10 of us,” Seawell said, referring to the number of teachers. “We need them to help each other.”

And it helps to have a special senior class that has built the school’s culture from the ground up.

“This senior class, they are a phenomenal group of children,” Beane said. “Next year is going to be tough not seeing them every day. They take the other students under their wing.”

And they do a bit of policing, too.

There are no bells sounding to signal change of classes. The early college sits in one of the college buildings, and they never needed school bells. There is no clear demarcation between the college and the early college, no real way to know which students walking around campus are college-aged or high school-aged.

But safety has not been an issue. The kids know where they can go and where they can’t. And if a student goes somewhere they shouldn’t?

“They tell on each other — really,” Beane said. “They’ll say, so-and-so did this or so-and-so said this. And we’re like, ‘Oh, we wouldn’t have known that.’ But they look out for each other. What they say is they don’t want them to make this mistake again or I want them to do this right the next time. It’s not, ha ha, they’re in trouble. It’s never that.”

College readiness focus

When an eighth grader matriculates straight to a college campus, teachers can’t expect them to be fully prepared for that transition. The students help each other, but systems had to be in place. Seawell said she, and the first teachers and staff on board, carefully prepared a schedule and put plans into place to prepare the students.

“We provide 100% support for their college classes for our students,” Seawell said. “We build that into the schedule.”

The first college course the freshmen take is essentially an introduction to the college experience. Professors talk about expectations and responsibilities. Afterward, students return to the high school classroom and get a chance to process the information with their teachers. The high school also works with students on skills like time management and e-mailing professors, things middle schoolers probably haven’t dealt with at length.

“We teach them how to advocate for themselves,” Seawell said.

The teachers sit down with the freshmen to give them an introduction to the changes they will see. They talk about how expectations in college courses are different, how grading is different, how most of the work must be completed outside the classroom. Then, the high school teachers make accommodations for large assignments from the college — offering support and high school class time for students to complete major college projects.

Given the high level of independence expected in college, the high school also makes teachers available to students for extra instruction. The students take college courses in cohorts so that the high school teachers can follow along with the college syllabus and communicate with the college professors. When extra help is needed, they can assist. For instance, math teacher Mishele Hare is teaching extra classes in the morning.

“And that’s something we’ve had to build,” Seawell said. “Imagine a high school coming onto a sleepy, college campus where they only ever taught six kids in the class and now they have full loads of 20-plus kids. And high school teachers are high school teachers, and college teachers are college teachers. Forming those relationships together has been a trust-building exercise the last three years that’s worked.”

So as the students grow comfortable with extra work, the high school teachers have had to grow accustomed to it, also.

“I work harder than I’ve ever worked before, but I love it,” Beane said. “I’ve had kids say, ‘You work all the time, do you go home? Do you sleep here?’ But it’s one of those things where I tell the kids if you’re going to work hard, I’m going to work hard. And if you’re going to be successful, you have to work hard.”

Beane stressed the importance of balance, though. Working on two degrees in the same four years is tough, as is teaching students while also serving as college advisors and helping them build a brand new high school experience. So they make concerted efforts to introduce fun.

“My kids know their objectives,” Beane said. “They know where they perform on those objectives. They track their own data. … We talk about the curriculum. But we also know that if that’s all we do, we can’t help them be ready for life. And I think that’s important. We know the expectations and our kids know the expectations. But we don’t cut out the fun to focus on that. We make the learning fun. That’s our goal.”

Leaving a legacy

The graduating class looks back and knows they have left a mark on this school, helping to build a culture of inclusivity and peer support. Now, they want to make sure they leave a legacy they can come back to visit.

That means homecoming. And a homecoming parade. And a homecoming dance. And a homecoming court.

And tacos.

“Nothing’s ever small here,” Seawell said.

As with much of the school’s identity, the senior class is putting their own spin on it as they work to redefine the traditional meaning of homecoming.

“Homecoming isn’t a football game here,” Seawell said. “Homecoming is something different, and they had to figure out what that something different is.”

Last month, the students led a drive to create a spirit week. Meanwhile, Seawell reached out to the community to see if they would participate, as well. The town of Troy puts on a large Halloween festival every year and suggested homecoming happen then. The town even convinced the school to hold the homecoming parade. It’s an opening act for the festivities, which include trunk-or-treat (it’s exactly what it sounds like), games, and live bands in an amphitheater.

Meanwhile, the students led the planning around homecoming court — which they didn’t want to become a popularity contest. Each club nominates a male and female, both of whom have to be active in the club, in good academic standing, and have had no behavioral issues this year or the prior year.

It’s all the trappings of homecoming without the helmets and pads.

“I get asked that a lot,” student body president Salgado said. “How are you having a homecoming if there isn’t a football game? But homecoming is the sense of coming back to something. It’s that no matter where we go in life, 10 years from now we can always come back to the parade we’re going to do. Come back to those tacos that are now a tradition here. It’s something to come back to, so you can talk to people and see where they are in life instead of just watch a football game.”

Each high school club is creating a float with the help of a teacher advisor. The community college students are doing floats now, too. Even the Troy fire department and the ROTC from one of the traditional public schools are going to participate.

And they’ll eat the tacos, an occurrence so anticipated at the school it draws giggles at the mere mention. A couple years back the student government was thinking up fundraisers when a student suggested her uncle make tacos for them to sell.

“We made like $100 the first time,” Beane said, adding that the line stretched down the long corridor of the building, out the door and into the courtyard.

They became so popular after the first go-around, students from other high schools tried to come on campus to buy them the next time. Last time they were sold, local businesses sent people to campus to buy up 30 tacos to take back to the office.

“They’re really awesome tacos,” Beane said.