|

|

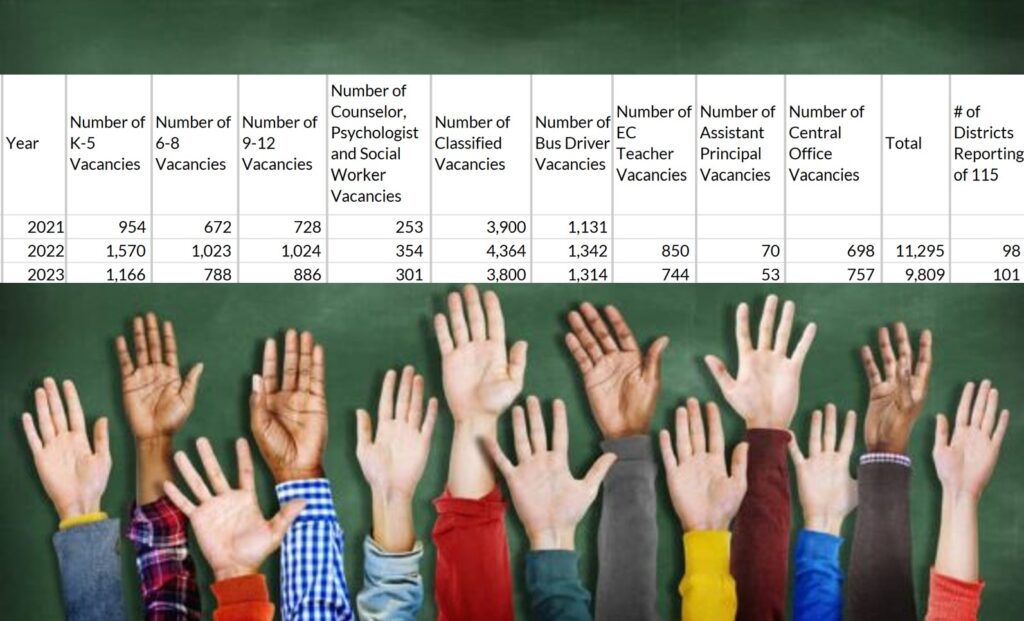

Jack Hoke is the executive director of the N.C. School Superintendents’ Association. He collects data from the superintendents about this time each year to find out where districts stand on vacancies.

This year, 101 of 115 districts responded to the survey.

Here is the summary data from 2021-23:

Note that year-to-year the data is not comparable because the number of districts reporting and the districts that participate changes.

Note, though, that with more districts reporting this year, vacancies across the board appear to be down compared to 2022, except for central office vacancies.

At the start of the 2023 school year, for the districts reporting, there are 1,166 K-5 instructional vacancies; 788 6-8 instructional vacancies; and 886 9-12 instructional vacancies. That’s a total of 2,840 statewide — about 3% of the teaching corps.

According to Hoke, of the 101 districts reporting, 13 have 0-1 instructional vacancies, 37 have 2-10 instructional vacancies; 17 have 11-20 instructional vacancies; and 21 have 21-50 instructional vacancies. Thirteen districts have more than 50 instructional vacancies.

That means 88 districts have fewer than 50 vacancies, compared to 81 districts last year.

Importantly, whether these numbers are a lot depends on the size of the district.

As a reminder, according to N.C. Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) annual report, the 115 districts included 2,484 traditional public schools with 92,681 teachers in 2022-23.

Hoke also asked superintendents the number of residency-licensed teachers they hired, and the total was 5,041 in 2023.

“The numbers have been large the past three years, up from 1,942 in 2021 and 3,618 in 2022,” said Hoke. “This illustrates the real shortage of certified teachers to me.”

According to N.C. DPI, “Residency licensing allows qualified individuals to begin teaching while completing North Carolina licensure requirements.”

Beyond the classroom, Hoke’s data also shows vacancies for counselors, social workers, and psychologists; classified positions; and bus drivers. Last year, he began capturing data on the teachers of exceptional children (EC), assistant principals, and central office staff.

When thinking about vacancy data, I worry most about classroom teacher, principal, and bus driver vacancies. Those vacancies create real pain points for students and parents.

Context for the data on teacher vacancy

Teacher supply is not a one-size-fits-all problem, nor is there a one-size-fits-all solution.

Much of North Carolina’s supply and demand issue has to do with the distribution of teachers across our state relative to shortages driven by geography, by challenges of particular schools, and by area of teacher specialization.

It is important to understand statewide teacher supply trends and to address the drivers of those trends, but it is just as important to understand whether teacher supply is healthy, adequate, or stressed district to district.

Over time, we’ve found that the following drivers are important at the local level:

- Salaries and compensation.

- Teacher preparation and entry.

- Hiring and personnel management.

- Induction and early-career support for teachers.

- Working conditions.

Additional factors we consider include: effective management at the school and district level; a strong culture at the school and district level; enrollment changes; whether the district is low performing; the age of teachers (older teachers are less mobile, younger teachers are more mobile); proximity to educator preparation programs; urban, suburban, and rural relative job opportunity; and the capacity of districts to diversify the workforce.

Within districts we look to see if the vacancies are evenly distributed across schools or if they are concentrated.

We always expect to see higher vacancies in elementary schools because there are more elementary schools.

We expect to see higher vacancies in hard-to-staff subjects like STEM and exceptional children.

More recently, we have noticed pandemic effects, including a rise in the number of positions because of the influx of federal COVID-19 relief dollars.

Our public school districts are the largest employer in many of our counties, and they, like all large employers, are used to not being fully staffed all the time.

Where to find state data and district by district data

Here is the most recent teacher attrition data — how many people are leaving the teaching profession — which can be found in the State of the Teaching Profession in North Carolina Report submitted to the N.C. General Assembly annually. This data is for the 2021-22 school year. Data for the 2022-23 school year will not be reported until February 2024.

Note that mobility is different from attrition. Mobility is “the relocation of an employee from one LEA/charter school to another within the state of North Carolina.” Often if teachers are unhappy, they change schools or districts instead of leaving the profession.

Key findings from the report, include:

Generally, North Carolina teachers are remaining in the classroom. The overall state attrition rate for 2021-2022 is 7.78%.

The attrition rate for Beginning Teachers in NC is 12.71%, higher than the attrition rate for those not classified as a Beginning Teacher.

While some LEAs can capitalize on teacher mobility, others experience teacher mobility as another obstacle to maintaining a strong, experienced teaching force.

— 2021-22 State of the Teaching Profession in North Carolina Report

This report also contains vacancy data by district. In Appendix D for all 115 districts, you can see total positions, vacancies on the first day, vacancies on the 40th day, and vacancy rate. You can also see vacancy data for selected subject areas.

If you are a student sitting in a classroom on the first day of school and you have a substitute, that’s one thing. If there is still no teacher on the 4oth day of school, that’s another thing.

All districts should be striving for 0% teacher vacancies on the 40th day of school this year. In 2021-22, just five districts statewide had 0% vacancies on the 40th day.

Here is a recent report by the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina (EPIC), but note the researchers use a different definition of attrition. This study defines attrition as a teacher or principal leaving their respective role. Using that definition, the study finds that “educator attrition and mobility increased sharply between fall 2020 and fall 2022.”

What can the state do?

Teacher supply is a localized challenge that deserves the attention of the state, and not just at the start of school.

This issue is not new.

The N.C. Center for Public Policy Research has studied our supply of teachers for almost all of its more than 40 years, finding over and over again, starting in the 1980s, the need for “a labor pool filled with well-qualified teachers thoroughly prepared for the demands of today’s and tomorrow’s classroom, and retention and placement efforts strong enough that teachers stay on the job.” There were high water marks for attrition in 2000-01 and 2014-15.

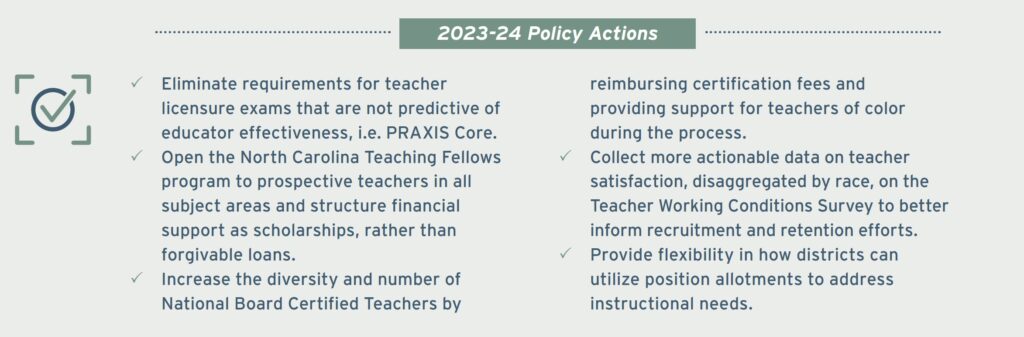

The Public School Forum of North Carolina identifies growing, retaining, and diversifying the teacher pipeline as one of the most important education issues facing North Carolina. Here are their recommendations: