Over lunch at Cé La Vi, the rooftop restaurant of the iconic Marina Bay Sands Hotel that dominates the harbor view of Singapore, Dustin Nichols and Stefanie Joyner tried all sorts of new foods. “I have had salmon before,” says Dustin, “but it was cooked.” Stefanie retorts, “I don’t each sushi, but I just put the whole thing in my mouth.” Our trip to Singapore changed these teachers.

Our fearless leader Alisa Chapman, vice president for Academic and University Programs at UNC-General Administration, says to the scholars during our final debriefing,

“We have a better sense of education systems. A better sense of the future of math and science education. You will be change makers — in your classrooms, in your schools, in your communities, and within our system of education.”

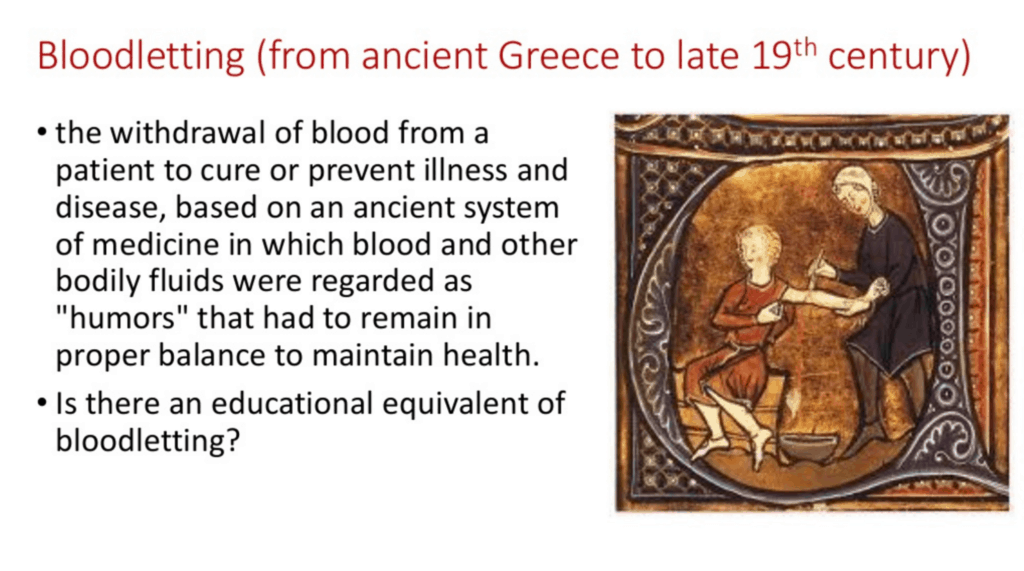

Bloodletting and the iron rice bowl

Two images frame my reflections on our trip. On the first day, we met with Adrian Lim at iDA (Infocomm Development Authority of Singapore). When he popped a PowerPoint slide up on the screen about bloodletting, it got a reaction from our teachers.

Lim suggested to our scholars that without an educational equivalent of bloodletting, our classrooms and schools and system of education are not “agile, nimble, and iterative.” They are not future forward.

Because of the country’s commitment to the development of human capital, teachers are respected and teaching is a coveted career in Singapore. Only about 40 percent of students go on to university, and of those, teachers are groomed from the top 30 percent. At Woodlands Secondary School, Principal Tan Ke-Xin says, “For most of us here, teaching is what we have wanted to do since we were young.”

Teachers are treated as professionals with office space in the school separate and apart from the classroom.

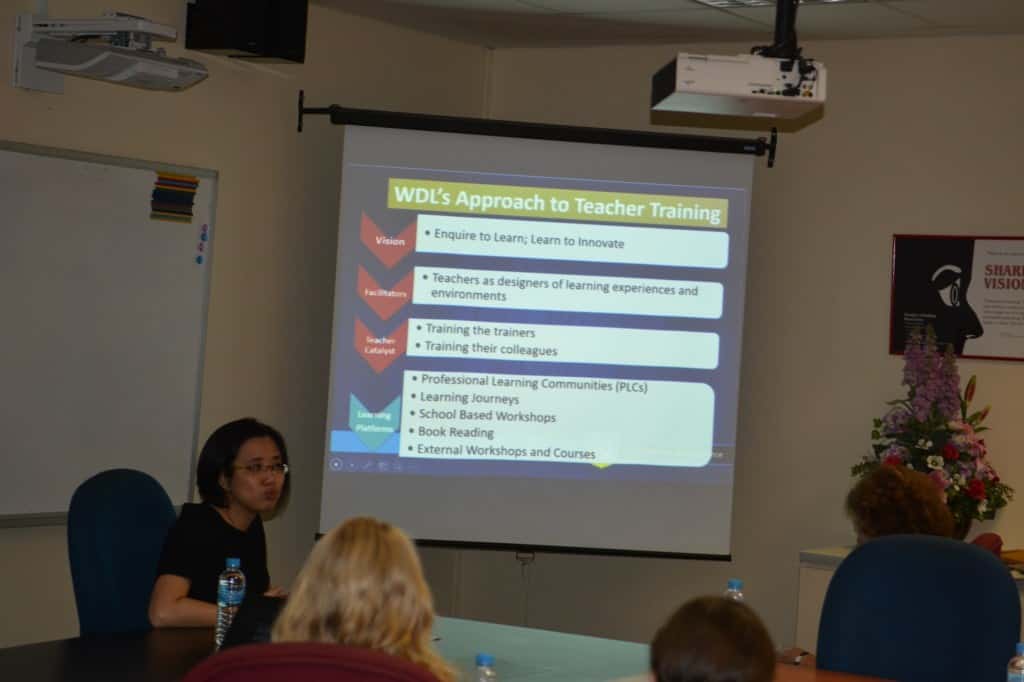

The national goal is 100 hours of professional development (PD) each year for teachers. Schools drive the PD experience. At Woodlands Secondary School, for example, 40 hours of PD happens within professional learning communities. Another 10 hours happens in reading groups for staff. Ten hours happens in on-site workshops. And twice a year there is learning fest to celebrate innovation in the classrooms and share stories of student success. The rest of the hours generally happen off-site, tailored to the needs of particular teachers.

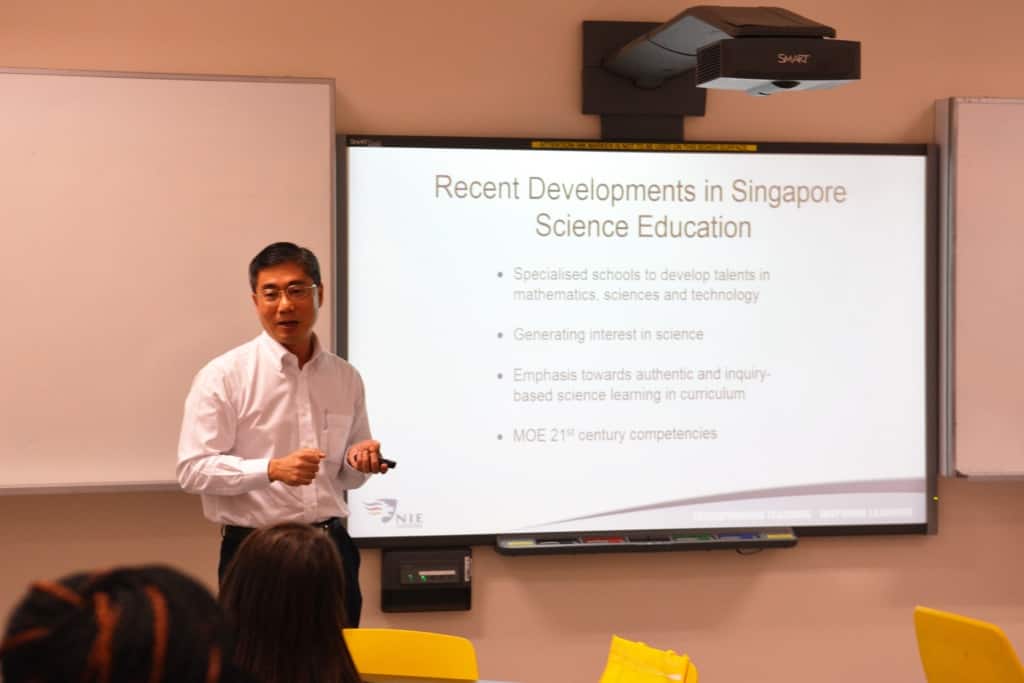

On the last day of our trip, we met with math and science teachers at the National Institute of Education, Singapore’s teacher training institute. Daniel Tan talked with us about the teacher pipeline and the support and security teachers in Singapore enjoy. He told us this career is like an “iron rice bowl.”

If North Carolina wants to have a world-class education system in the 21st century, the professionalism of teaching must be addressed.

A visionary system with school flexibility

Think about all the leaders governing our public schools in North Carolina: the Governor, the Governor’s Education Cabinet, the legislature, the Superintendent of Public Instruction, the state board of education, the chair of the state board of education, 115 school boards and superintendents for 115 districts, the county commissions that fund those districts, and all of the charter schools. Who is in charge? Who is driving our education policy?

In Singapore, from the top down, education is a national priority. The Ministry of Education sets the vision — currently to build a student-centric, values-driven holistic educational experience for students. Every five years, the MoE releases a new master plan and those changes are implemented in classrooms across the country within one year. But how teachers teach, what they teach, and professional development are left to the experts — the schools. “We make sure there is alignment,” says Lee Siew Lin, a master teacher at the Academy of Singapore Teachers.

Stefanie Joyner says, “Everyone is collaborating for the common good of the students as well as the country.”

A focus on ALL

The economy in Singapore depends on having an educated work force. The focus is not just on the best and brightest, as you might expect, but on all students. Resilience, a hot topic back home, is one of the six national values for students.

Our tour guide Jeremy points out in a neighborhood not far from our hotel a Buddhist temple, an Islamic mosque, a Hindu temple, and a Methodist church all built in close proximity to each other. The idea is to minimize othering.

Lots of support exists in schools for students receiving financial assistance: uniforms, shoes, eyeglasses if needed, transportation, vouchers for food, textbooks, enrichment programs, an opportunity to visit overseas, and financial support to purchase a laptop, among other programs.

Elizabeth Cunningham, the assistant vice president for Academic and University Programs at UNC-GA, challenged us to think about how we built our system of education.

With a system of education that is focused on all students comes a focus on fit, as we see in our own state. Parents want a school and an educational experience that is the right fit for their child.

At the School of Science and Technology, Singapore, Donald Treffinger’s talent development model is used to nurture, develop, and sustain differentiated student growth.

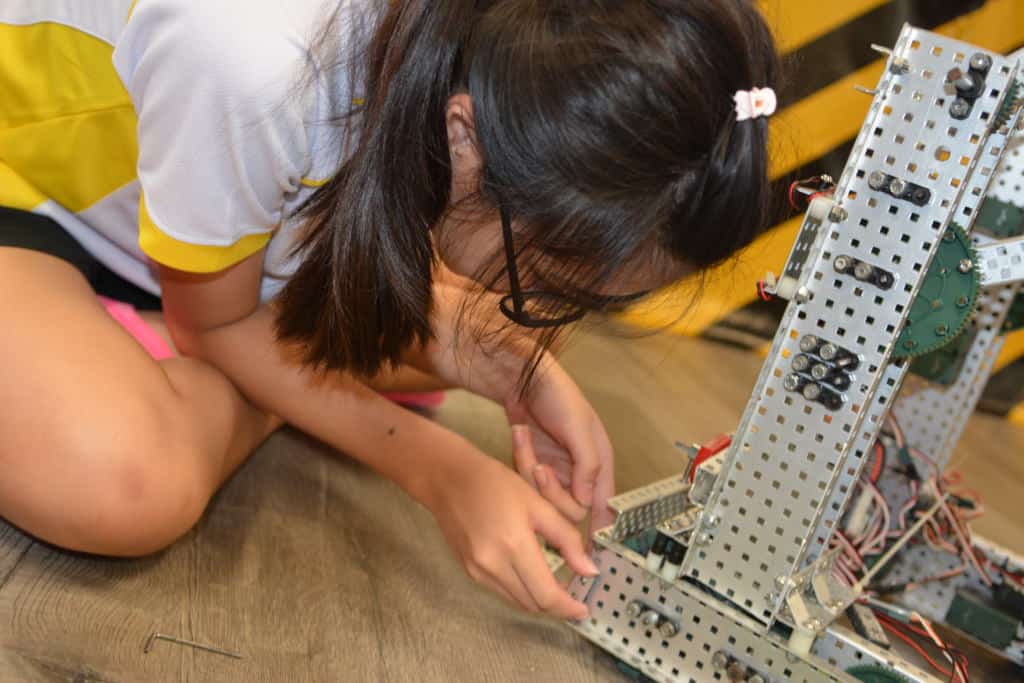

Girls in STEM

Despite the country’s commitment to the education of all and the “everybody counts” philosophy, my visit to Singapore exacerbated my own concerns about educational opportunities for girls worldwide, especially in STEM fields.

At the School of Science and Technology, Singapore just 30 percent of the students are girls.

Samiya Nadaf is a coding instructor for First Code Academy, a start up that teaches children how to code. “I never realized there is a gender issue until I started teaching,” she says. “As soon as we move on to teaching secondary students, there is one girl to every seven or eight boys. Of course, this is surprising and really, really disappointing.” Nadaf looks forward to a future where it will be second nature for girls to code.

“We have to ask ourselves why this happens?,” says Nadaf. “It is a stereotype that is created by society. All of us.”

“Gender issues in the start up world are very real,” says Grace Sai, the CEO and founder of the Impact Hub Singapore. “Changing it starts with teachers.”

The link between failure and innovation is important. “We have to make it ok to talk about failures,” says Sai.

Heading home to North Carolina

Stephanie Evans will change the way she teaches after seeing how technology is integrated in the classrooms in Singapore. Shane Castevens returns home even more strongly committed to project-based learning. Kayleigh Willis wants her students to be more responsible digital citizens, learning how to use social media for good. Megan Alvord snagged a lesson plan on kinematics while we were visiting the Academy of Singapore Teachers that I bet finds its way into her classroom.

“There are takeaways,” says Andromeda Crowell, “that inspire us, and we can take back to our schools.”