In North Carolina, 85.3% of households have a broadband internet subscription at threshold speeds of 25 Mbps, according to 2019 American Community Survey one-year estimates. But as classes moved online last spring, students in the state’s remaining 583,000 homes were left looking for a solution.

Ray Zeisz, director of the Technology Infrastructure Lab at the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, said a diversity of solutions have been implemented through trial and error over the past year, marking a significant increase in urgency around the issue of broadband internet access.

“I would say 80% of the acceleration is a result of COVID,” he said. “COVID made it painfully obvious of the difference between the people that do and don’t have internet, and I think people quickly realized how unfair it was.”

Zeisz said North Carolina’s rural population distribution presents its own unique hurdles.

“When you look at a state like Utah, the populations are really clumped together, and then you have a long stretch of desert with no one. In North Carolina, every 10 miles you drive there’s a little town. So we have this weird population density problem in North Carolina where we can hit a lot of the people pretty easy, but the ones that we can’t hit are out there in between the two towns. They have a completely different model for their ‘ruralness’ than we do,” he said.

“We have a lot of people — like millions of people — that live in between the towns. And that’s I think what makes it harder for us.”

– Ray Zeisz, director of the Technology Infrastructure Lab at the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation

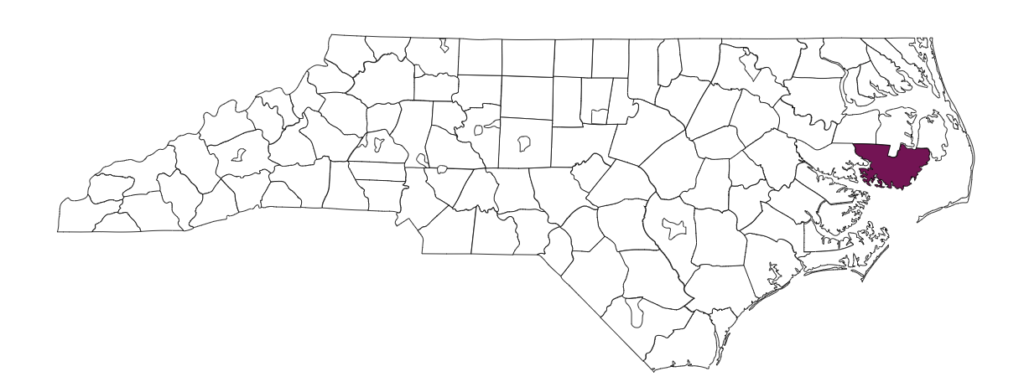

Hyde County

Hyde is the state’s second smallest county by population. It is anchored by Ocracoke on the Outer Banks, and Engelhard on the mainland — both towns with populations less than a thousand.

Steve Basnight is the superintendent of Hyde County Schools. He said differences in geography between parts of the county have called for different broadband solutions.

On the island, Ocracoke was chosen as a location for a pilot program of SpaceX’s Starlink internet service.

Elon Musk’s Starlink has been launching thousands of small, low-orbit satellites that can send broadband into homes via a receiver residents can purchase.

“What SpaceX has done is they’re putting satellites so close together in orbit that when this one passes out of range, it picks up the signal of the very next one,” Basnight said.

The pilot program in Ocracoke will fund 47 receivers and a year’s worth of service for qualifying households, replacing the wireless hot spots the school district originally provided.

“What we did with the hot spots, we went to the people that really did not have internet access. That’s what we got them originally. And we thought that would be a good place to start in getting satellite technology,” Basnight said. “So we’re going to replace those hot spots and may be able to take them and give them to somebody that has some internet access, where we can actually improve their access through the use of that as well.”

On the mainland, existing infrastructure is providing an opportunity for another solution to be implemented.

“We’ve started researching the possibility of something called TV whitespace, which is basically unused cables. And Hyde County, luckily, has a lot of unused cables,” Basnight said. “We’re able to sort of jump a broadband signal onto that unused cable signal.”

Zeisz said the signal transmitted over existing, unused television cables can be broadcast several miles from a high elevation point, even without cable going directly to every home.

“That type of network has the ability to run several miles. So on a water tower or a grain silo or whatever, you can put up these things that are Wi-Fi access points that shoot many miles and to dozens of families. And so that’s what we’re doing on the mainland,” he said.

Zeisz said he hopes the pilot programs can turn into a consistent service provided by private companies.

“The goal of this project is at the end to get a working business model in Hyde County so that the students are all getting internet access for free for the first year or two, but the emphasis is for the company to invest enough infrastructure that they can offer the services to local businesses and people that don’t have kids,” he said.

“The idea is to really just use education access as the seed to get the ball rolling in a place that’s very challenged in terms of the business model.”

Ray Zeisz, director of the Technology Infrastructure Lab at the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation

Basnight said he hopes to see more applications of sufficient broadband coverage in Hyde, from telehealth to school psychology. And he said the applications for online learning don’t stop with COVID-19.

“What if we could protect instructional time? Every time we have to be out of school for a snow day, a flood day, wind, a hurricane — what if we could just go virtual?” he said. “We have one hurricane that comes close and we’re out for three days. When it hit us on Ocracoke, we were out for September and most of October. What if we could mitigate that? And that’s what this technology enables us to do.”

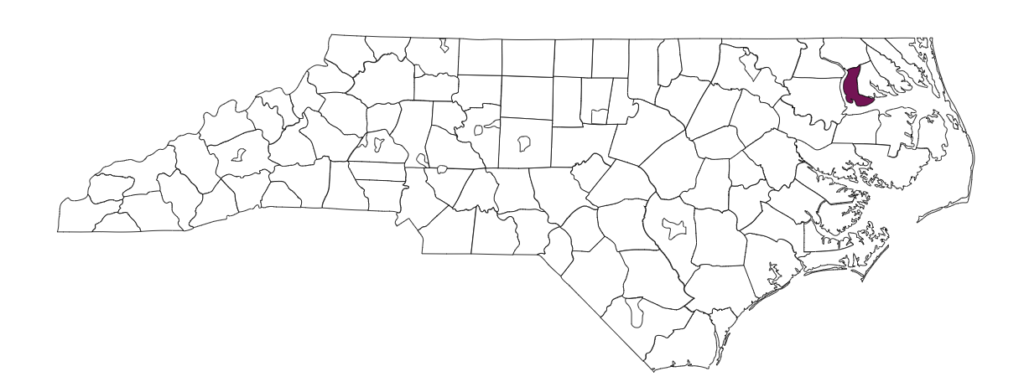

Chowan County

Chowan County is geographically smaller than Hyde and doesn’t require a two-hour ferry ride to get to parts of the county. They parked school buses with hot spots on them around the community to help students and families without broadband access at home.

“During the height of the COVID situation, we actually deployed wireless hot spots on school buses and would drive them out to a community central area and park. And then we’d let the families know, ‘Hey, there’s a hot spot in the parking lot of Warwick Baptist Church,’ or wherever we would park it so that they could go there to get to do their homework,” said Bob Kirby, chair of the Chowan County Board of Commissioners. “And of course, that’s a band-aid fix, it really is. But it is as much as we could do under the circumstances.”

Patti Kersey previously served on the Chowan County Board of Commissioners and now sits on the Board of Trustees for College of the Albemarle. She believes the state should take a more centralized role in addressing broadband access.

“I think competition, which we don’t have a lot of, would get the legacy providers a little more motivated to do something. I get the financial dilemma they have,” she said. “But I’ll tell you after doing whatever we can to leverage to get better service, I’ve just come around to the conclusion that it’s got to be a state mission. We’ve got to get the legislature putting this first and foremost and addressing it.”

Kersey said that outside of applications for online learning, sufficient broadband infrastructure would help bring employers to communities in Eastern North Carolina.

“We’re constantly trying to attract businesses here,” she said. “And now with everybody wanting to work from home, it’s even more complicated and difficult for us to.”

Zeisz said a statewide program has become necessary, naming the Department of Public Instruction’s School Connectivity Initiative and the Broadband Infrastructure Office as natural state agencies that could be involved.

“I think that the money shouldn’t just be like a block grant out to the districts. I think we should really focus on putting together a menu of items that we know work and make sure people aren’t off wasting money buying things that don’t have a chance of working,” he said. “We saw tons of cellular hot spots get bought this year that are sitting on shelves not being used, either because they can’t afford to pay for the service or because they were given to kids that don’t live within sight of a cell tower. We need to not be repeating that this time around.”

The Growing Rural Economies with Access to Technology (GREAT) Grant — passed in 2018 — provides funds to private internet service providers to deploy broadband access to unserved areas of the state. But Zeisz said it hasn’t gone far enough.

“The GREAT grant program that they already distribute has done a lot, but it’s only around $20 million a year,” he said. “I think we’re talking an order of magnitude more, you know this would be a quarter billion dollars a year kind of project for the next five years probably. But I do think there’s an end in sight. If we can get the proper level of funding for five years, we can substantially hit most of the rural places.”

Kirby said he looks forward to a day when Starlink will be available to students in Chowan County. But Kersey said students taking online courses right now can’t wait on the low-orbit satellite connection to be implemented.

“I think that satellites would be wonderful. I think near term, the legislature needs to relook [at] the GREAT Grant and just put some guardrails around it and give local governments a little more flexibility,” she said. “We have elected officials who are responsible that people see welfare from their money. So give us that opportunity to make those decisions.”

“One size doesn’t fit all. We just like a little more flexibility.”

Patti Kersey, former Chowan County commissioner and trustee at College of the Albemarle

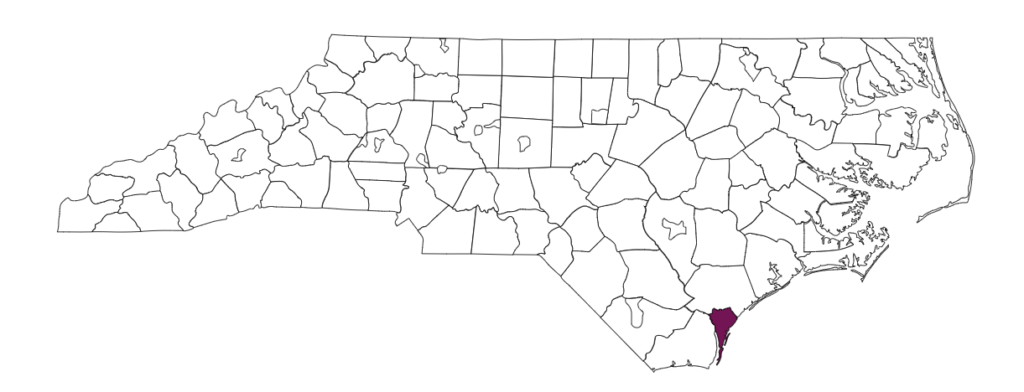

New Hanover County

A partnership between the Institute for Emerging Issues at NC State, the state’s Broadband Infrastructure Office, and the John M Belk Endowment formed the BAND-NC grant program, providing “mini-grants” for communities to meet immediate digital inclusion needs.

In Wilmington, directors at Cape Fear Collective are using their BAND-NC grant to bolster the broadband capabilities of existing community centers that have turned into remote learning centers during COVID.

“We knew that they had broadband, or Wi-Fi access, but probably not to the extent that they needed it for dozens of children eight hours a day,” said Kate Groat, board member at Cape Fear Collective and director of corporate philanthropy at Live Oak Bank. “So we just went in and bolstered whatever they had in existence.”

Meaghan Lewis, director of programs at Cape Fear Collective, said they’ve been able to broadcast the signal from the community centers into the some of Wilmington’s most underserved neighborhoods.

“We really focused on remote learning sites at nonprofits in town and some of these afterschool programs that were set up to carry on remote learning for their students, obviously with social distancing and safety precautions in mind,” she said.

The mini-grants weren’t meant to fund a community-wide infrastructure project, so Groat said they looked for a different approach.

“We just asked a different question,” she said. “Instead of asking, ‘Where is there not internet?’ We said, ‘Where will the children be?’ And we went where students are rather than to where the internet was not.”

Even pre-pandemic, many students found themselves in the “homework gap,” occurring when students are assigned homework that requires reliable internet access that they don’t have at home.

Lewis said over 2,000 students have been served through Cape Fear Collective’s BAND-NC grant. But she said it is not a long-term solution.

“I really don’t know how we would have not to say we solved the issue, but how we would have supported folks if they weren’t in these high, densely populated areas,” she said. “We provided a year of service, but what does it mean when that year is up?

Zeisz said students have been experiencing inequalities in education related to broadband access for years, and that COVID-19 has just made those gaps wider.

“If we want to really attack the inequality, broadband is a pretty important thing in education now if you actually want to get a valuable, useful education and be on the right track for a career.”

Editor’s Note: The John M Belk Endowment supports the work of EducationNC.