As Dezerea Hummel had lunch outside Marine Science and Technology (MaST) Early College in Carteret County, she talked about how, as a first-generation college student, the early college gave her the chance to ‘kill two birds with one stone’ — tackling high school and college at once. The entire experience, she said, is wrapped around the student’s interests and plans.

“It’s kind of nice having somebody care about what your future looks like,” Hummel said.

Across North Carolina, students at over 130 small public high schools earn college credits while they work towards graduation. Many finish high school with an associate degree, some with workforce credentials or certificates, and some with a handful of credits transferable to four-year universities.

Though these schools, known as Cooperative Innovative High Schools (CIHS) in state legislation, have a variety of missions, subject focuses, and strategies for success, the nontraditional environments often offer students something regular high schools may lack: personalization.

MaST Early College was one of seven CIHS’s to open this year and is serving 50 ninth graders like Hummel.

“[Teachers] want to connect more with a student one-on-one instead of connect with the class,” Hummel said. “It’s more, like, on a personal level. They tend to connect with your personal needs. So, like, if you need help with one thing that maybe the rest of the class doesn’t, then they make out time to come and work with you whenever you need it.”

In a state with some of the most early colleges in the country, the model provides a look into what students need to succeed and what success means in a changing North Carolina.

At a glance

According to the Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) definition, CIHS’s are built around “high quality instructional programming” and target certain student populations: students at-risk of dropping out of high school, first-generation college students, and students who would benefit from accelerated instruction. From the DPI website:

“North Carolina’s early colleges and other innovative schools are small public high schools, usually located on the campus of a university or community college, which expand students’ opportunities for education success through high quality instructional programming.”

“It really is a blending of we need to know these students well, care about them well, support them personally and academically — but that combined with rigor and innovative instruction,” said Isaac Lake, a state consultant for DPI’s division of advanced learning and gifted education.

Out of 133 CIHS’s, 90 have “early college” in their title. Most CIHS’s are located on the campus of a community college or university. Each grade has a cap of 100 students, but many are much smaller. Some are middle colleges, which also offer smaller classes and usually focus on students struggling in a traditional environment. Others have specific focuses, such as science and technology, teaching, health sciences, or career readiness.

At MaST, the school’s focus is marine sciences. As with other early colleges and innovative schools with a specific focus, not all students are interested in or take courses in marine sciences. Principal DeAnne Rosen said it was important to open an early college in a district without one to give a different kind of option for students. Its partner institution, Carteret Community College, was one of three community colleges statewide without an early college.

“Even though we’re in the top 10 percent of education in North Carolina as a county, we still were not serving our students to our fullest potential,” Rosen said. “And so that’s where this model came into play.”

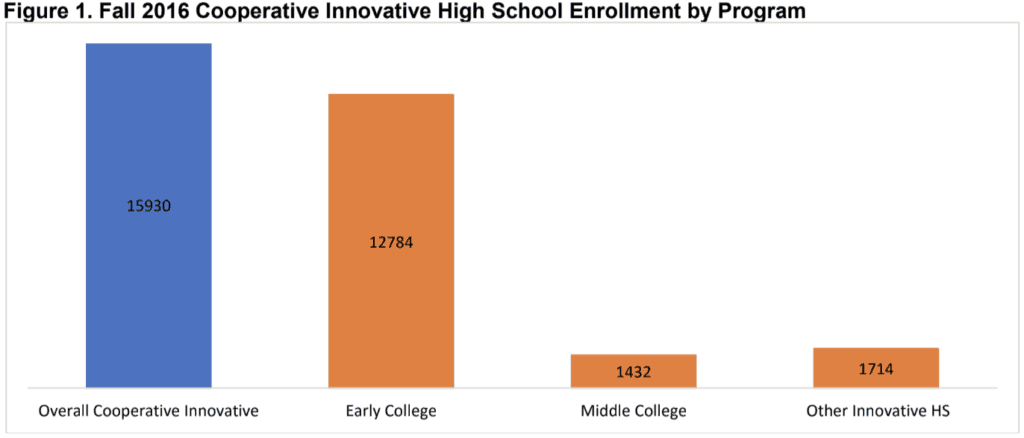

Below is the breakdown of CIHS enrollment by school type in the 2016-17 school year.

CIHS’s are spread out across the state, with 97 of 115 school districts having at least one. Guilford County has the most with 11 schools. Seven CIHS’s opened this school year. View the geographic distribution of CIHS’s statewide below. Yellow markers indicate new schools. Scroll over a marker to view the school name and partnering institution of higher education.

Last year, CIHS’s scored higher on state performance measures than public schools overall. In 2017-18, 72 percent of CIHS’s (90 out of 125 schools) received a school performance grade of A compared to only 6.5 percent of public schools statewide (173 out of 2,642).

Other academic measures, like high school retention and completion, individual assessments, and high school drop-out rates indicate CIHS’s above-average performance. Out of the 4,869 students graduating from CIHS’s in 2017, 1,165 graduated with career credentials and 2,214 graduated with an associate degree.

View the map below to see the distribution of performance grades. These grades, given to all public schools in the state, are based on a formula of 80 percent achievement, or test scores, and 20 percent year-to-year growth.

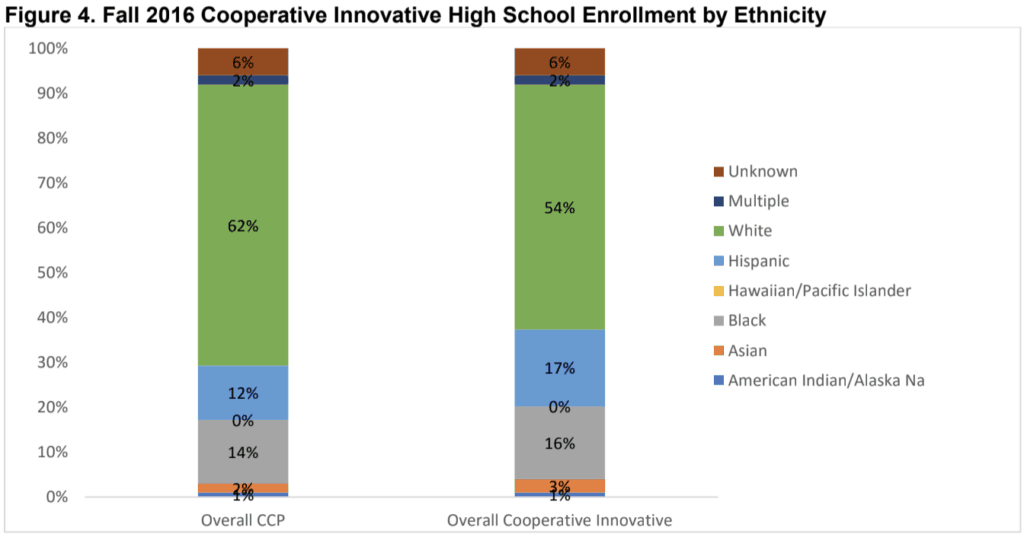

The demographic breakdown of CIHS’s from fall 2016 is shown below compared to the demographic breakdown of all students taking college-level courses through Career and College Promise (CCP).

Districts and institutions of higher education must jointly apply to open a new CIHS. A Joint Advisory Council (JAC) made of representatives from DPI, the North Carolina Community College System, the University of North Carolina General Administration, and the North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities decides whether or not to recommend the school to the State Board of Education.

If the Board approves it, the application goes in front of the governing board of the partner institution and then to the legislature. The General Assembly decides whether or not to open the school, and, if the school requests supplemental state funding, whether or not to allocate those funds.

CIHS’s are reviewed every five years and submit annual reports to DPI, which then submits annual reports to the General Assembly. The latest report on the 2016-17 school year is below.

How we got here

Though early colleges are now more popular, middle colleges came first. Lake said middle colleges popped up during the 1990s primarily as two-year programs focused on dropout prevention. Some are still operating today.

At the Middle College on NC A&T’s campus, Principal Travis Seegars works with an all-male student population that is majority minority. Seegars, in his second year as principal, says the environment meets the needs of “young men that didn’t fit the general mold.” Through small classes, intimate relationships, and peer collaboration, the school has had a 100 percent graduation rate for eight years. We will take a closer look at the Middle College later this week.

After former Gov. Mike Easley took office in 2001, he became interested in the idea of early colleges, looking to leave his mark as another North Carolina “education governor.” After a $20 million investment from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to experiment with small schools, the General Assembly passed legislation in 2004 matching the Gates funding.

The legislation established Cooperative Innovative High Schools and focused more on the early college model than the structural change the Gates funding went towards. The establishment was a collaboration between DPI, the North Carolina Community Colleges System, the University of North Carolina General Administration, and the North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities. A public-private partnership called NC New Schools Project helped to start and support the CIHS network from the beginning until its closing in April 2016.

The governor’s prioritization of the project, bipartisan support from the legislature, and momentum from the Gates investment started a movement, Lake said. Between 2004 and 2011, more and more districts applied to open early colleges. “The expansion just grew like wildfire,” said Lake, driven by districts’ thirst for the opportunity to try something new and provide choice for families within the public school system.

The state’s unique network of 58 community colleges also gave CIHS’s a framework from which to build. Community colleges were looking for ways to partner with their school districts, Lake said, to increase enrollment and boost their regions’ economies. Part of the CIHS application process requires an explanation of how the school aligns with the regional economic vision. At MaST Early College, which partners with Carteret Community College, one can easily see how the partnership aligns with regional needs. Carteret CC has the only saltwater aquaculture program in the state, along with welding, marine propulsion, and boatbuilding courses specific to the coastal region’s economy.

“It goes back to exposing them to everything offered on this campus,” Rosen said. “We have the flexibility where we can just walk to the building and they can see aquaculture with the touch tanks … then you go to marine propulsion and talk about the market for outboard motor repairs in our area and how that is growing as a demand in our area. Just giving them that hands-on experience and exposing them … We even have kids interested in culinary, which is really big on Carteret Community College’s campus.”

The legislation outlining what CIHS’s are and how they should be run has changed over the years, from 2004’s Learn and Earn Initiative to the updated Innovative Education Initiatives Act and, in 2011, the Career and College Promise Program.

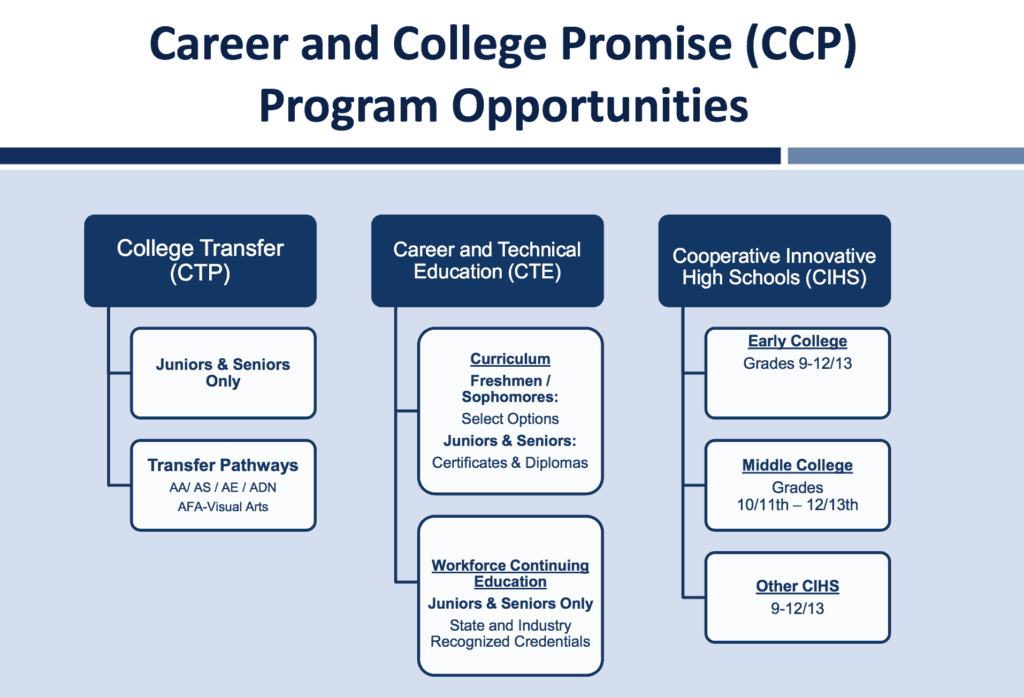

All of dual enrollment — or earning college credit in high school — falls under the Career and College Promise Program, with CIHS’s being just one option. Below is a graph from a March 2018 DPI presentation to the Joint Legislative Oversight Committee on dual enrollment explaining the three different dual enrollment pathways in the state.

What’s next?

The expansion of CIHS’s has started to slow in North Carolina. Lake said this year only two schools applied to open in 2019. That’s mainly due to reaching a capacity limit, he said. Most districts who have institutions of higher education with whom to partner have done so.

Lake said he has seen a transition in focus in newer CIHS’s away from college transfer and towards career readiness. This matches a recent statewide political and philanthropic emphasis on postsecondary attainment through opportunities beyond four-year universities.

“There are a lot of opportunities in local economies and a lot of workforce development projections that say a lot of young people will find opportunities with career-ready degrees and credentials in everything from health services… to HVAC, collision repair, welding — I mean a lot of jobs,” Lake said. “We’re going to need a lot of people to fill those jobs.”

The fact that newer CIHS’s focus on career and workforce readiness also has to do with districts that already have early colleges looking for another option for families.

“It’s districts saying how can we offer another school of choice that doesn’t duplicate what we’re doing with our existing early college,” Lake said.

Legislative funding also makes a difference and has changed in recent years. Historically, each school that applied for supplemental funding received $300,000. In 2017, the legislature changed that to depend on the district’s economic tier.

“That meant a reduction effectively in supplemental funding for most of schools that were receiving it,” Lake said.

Innovative high schools, dual enrollment, and early colleges have all grown nationally. Texas now has the most early colleges in the country, and states like New York, California, and Ohio have also seen the model pick up momentum.

Joel Vargas is a vice president at Jobs for the Future (JFF), a workforce development organization that emphasizes private-public partnerships. He said the organization has been behind the early colleges movement from the beginning. When early colleges first started, Vargas said there was a clear definition of what they were — specifically that they targeted groups of students who were underrepresented in the postsecondary space.

“The early college design and strategy from the go is sort of counter-intuitive, like, ‘You’re going to take kids who struggle typically and help them to go faster?’ And, [we’d] say, ‘Yeah, we can do this, and we have proof that that works.'”

Today, there is much more variety in states’ definitions of early colleges. Some target students who are academically gifted. Nevertheless, the idea of taking college courses in high school is continuing to grow, he said.

“States, I would say, they’re very interested in the concept, but… there’s variation in terms of how tight the definition is around what an early college is,” Vargas said.

In recent years, JFF has tried to take the early college model into comprehensive high schools. Vargas said it has been difficult because of the larger environment and pre-existing school culture and belief systems. Though the progress is slow, he said they have seen aspects of the model like student supports, close relationships with teachers, and college-readiness be effective in traditional high schools.

“As challenging as it was to start something new, you do get to start with a new approach, recruit teachers and leaders who are like-minded, and there’s a certain specialness in that, even though they’re working with populations that have traditionally been underserved,” Vargas said. “Even in the large schools, they’re more successful when they figure out how to also personalize the education experience.”

He also said the model needs to make sure to include the fastest growing demographics in the country. Minority and low-income students are underrepresented nationally in early colleges, he said, and he hopes to see that change.

“Even with that growth, there is still underrepresentation of participation by black and Latino students and low-income students,” Vargas said. “That data is pretty clear. So one aspect of where it could grow is reaching populations that are the fastest-growing.”

This is part one in a series on CIHS’s. Part two will look at the research documenting the positive impact of early colleges, while parts three, four, and five will take an inside look at four different early and middle colleges.