High school sophomore Lamya Powell remembers getting into DC Comics as a kid, except for her, it wasn’t about the superheroes.

“I never really looked at Flash or Superman or Green Arrow,” she said. “I was always looking at Felicity, the tech person … and Batman, who made his suit.”

That’s when Powell knew she wanted to be an inventor, but she never knew what that word meant in the business world or to regular people. Then, she learned the word “engineer.”

“I was like, ‘Oh my God, that’s the word! That’s what I want to be!'” Powell said. “I want to be an engineer. I want to make stuff. I want to help people.”

“I [had] so many things going on in my head, just no way to do them,” she added. “When I came here and I saw these makerspaces, I can really put what’s in my head [into] real life.”

She was standing in a makerspace at DePaul University in Chicago called the Idea Realization Lab, with the sound of woodworking power tools roaring around her.

It was a Monday evening in early March, and that upcoming weekend she would be participating alongside her teammates, the Chicago Knights, in the FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC) Midwest Regional.

“Last year, we went to world competitions for FRC,” she said. “I didn’t see a lot of people that looked like me. I really didn’t. We were in Detroit, and so I saw … teams from Russia and France. We saw Koreans, Japanese, and a bunch of American teams, but they were all mostly white guys.

“I was like, ‘Wow, there’s really not a lot of people who look like me in this field.’ I don’t know if that’s an advantage or a disadvantage,” Powell said. “I see it as kind of both because on one hand, colleges will be like, ‘Oh my God, it’s a black girl interested in engineering’ and diversity — but at the same time, it’s like, ‘Oh, it’s a black girl. We don’t know what to do with her.’”

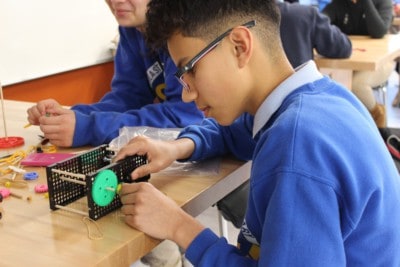

Powell joined the Chicago Knights Robotics team, also called FRC #1739, two years ago. Since joining, she’s learned to work every last one of the machines in the Idea Realization Lab.

“I think we’ve been able to take a step forward in learning some really modern technology,” said mentor James Dowd, who has been a part of the Chicago Knights Robotics team for 10 years. He helps students get comfortable using machines like laser cutters, X-Carve machines, 3D printers, and CAD (computer-assisted design) software.

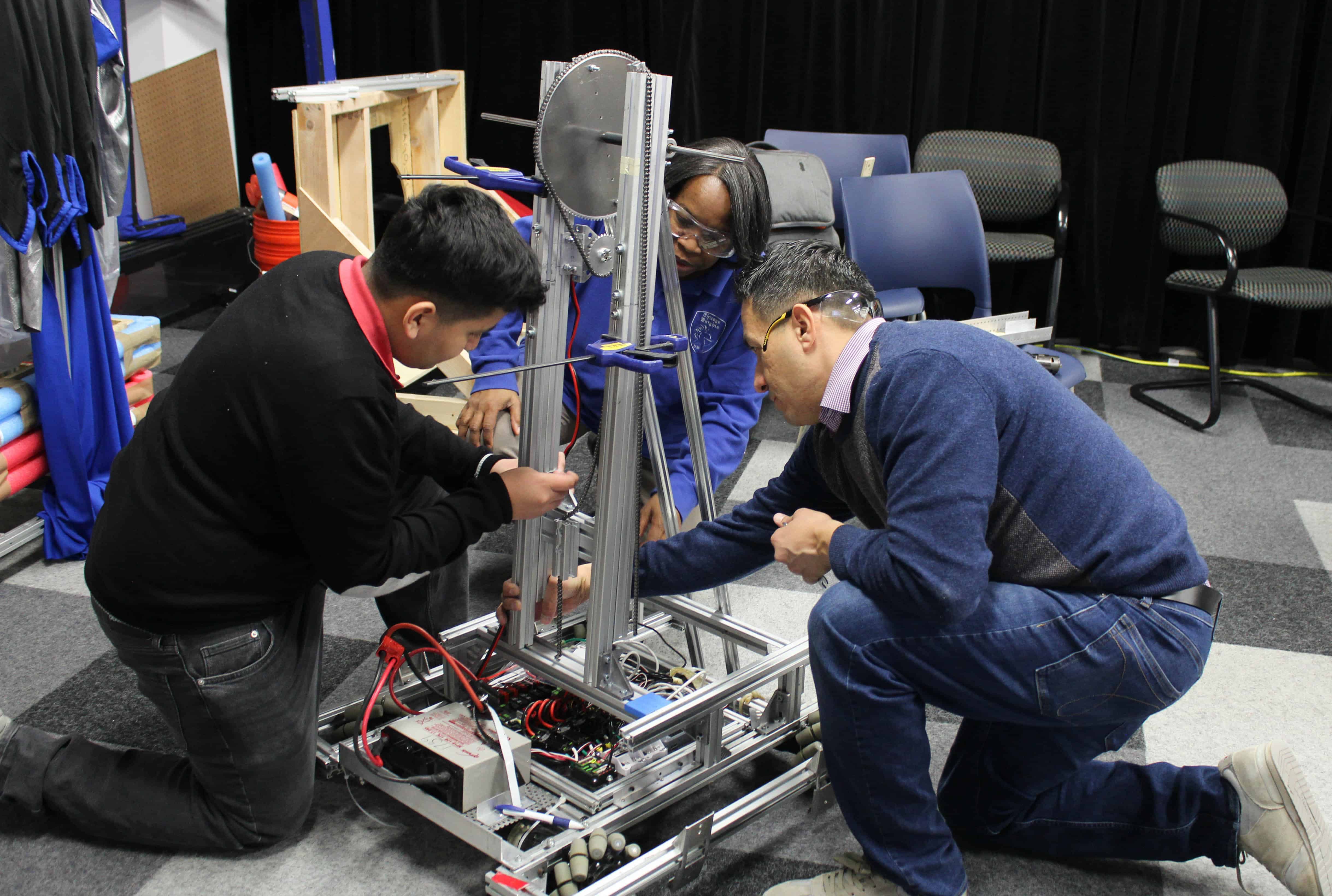

Still, he said most of the mentors take a hands-off approach, because it’s the students who are hands-on.

“In the long run, it’s important for the students to learn and grow and try to figure out some of this on their own,” he said.

The student-focused problem solving was one of the most memorable aspects of being part of a high school robotics team for Dowd — so much so that he stayed involved with robotics by becoming a mentor in Ann Arbor while he was a student at the University of Michigan. When he moved to Chicago, he was looking for volunteer work and found the Chicago Knights Robotics team, though his day job is in financial technology consulting.

That evening, he was helping Powell and her teammate Josiah Smith use the X-Carve to cut an enhanced side panel from a CAD design.

“I gave it a try, and I actually just fell in love with it. It’s so fun,” Smith said of his first year on the team.

“What I learn here is a lot more hands-on than what you learn at school, because at school you can see it in a textbook, you can see it in a video, but it’s nothing like grabbing the real thing and putting it together, seeing if that’s right or wrong, and then fixing it,” he said. “That’s really the benefit of this.”

And, according to Powell, robotics has taught her countless lessons, from patience to testing everything to designing a project before jumping into it. She said it’s also taught her a lot about what it means to be on a team.

“You have to learn to trust other people. You have to learn to depend on other people,” she said, all the while speaking highly of her teammates.

“He’s really smart, really intelligent. Jokes around a lot,” she said of Smith.

Josiah’s mother, Dorsey Smith, was eager to place her son in a robotics program after he had expressed interest at a young age. Now, she said her son will come to robotics meetings on his own, without her, even without a way back home — because that’s how much he loves being there.

“A place like this is important because this is community-based, it’s not in school,” she said. “He doesn’t have this opportunity in school.”

Because the Knights are community-based, it not only means students who don’t have a robotics team at their high school can participate, it also means that home-schooled students can participate. This model is based on the vision of the team’s founder, Jackie Moore, who started the team in 2005.

“She’s one of the most dedicated people that I’ve ever come across. She lives and breathes this, and she does so for the students,” Dowd said of Moore. “I really admire the tireless effort that she makes to make this happen.”

Powell learned about Chicago Knights Robotics through her grandmother, who went to the same church as Jackie Moore. “I didn’t even know I was into STEM until I met her,” Powell said of Moore. “She’s the reason why I’m going to major in electrical engineering.”

Currently a sophomore at Whitney Young Magnet High School, Powell said she has her eyes on universities like MIT, Cal Tech, UC Berkeley, and Stanford. Because many of the Chicago Knights Robotics team members left for college last year, Powell has witnessed the academic success of her teammates.

“I just want to make a difference, basically,” she said.

Powell may not know it, but the exact same sentiment likely led Moore to start the community-based robotics team 14 years ago when she was looking for academic opportunities for her own children.

“All the activities that I found were located [far away from home],” Moore said.

She said she also realized that taking care of her own children was not enough.

“I made a conscious decision that point forward, that whatever I did had to be open to everybody,” she said. “If I wanted my kids to have exposure to diverse types of people, I couldn’t say, ‘Only folks who live next door to you can come.'”

And Moore’s philosophy of diversity went well beyond skin color.

“When I talk about diversity, I’m not talking about things you can see,” she said. “Our home-schooled kids, parochial school kids, private school kids, drop outs … when you bring a diverse set of academic experiences together, something magical happens.

“The kids who have had the lesser quality academic instruction [teach] those more privileged about innovation,” Moore said. “Because they’ve had to scrap, they teach them about persistence. Because they had to keep pushing through.

And those with the better academic preparation can help those with lesser academic preparation with basic skills because they know them, they have them. But more importantly, those with the academic privileges can open the eyes of those without it [to show] what’s possible out there.”

Regarding her own educational background, Moore said she had a great K-12 education, but that she never received a college degree after leaving college during her junior year. Instead, she got her start through an in-house training program, working her way up in mainframe technology software support as a system programmer.

She not only had an unconventional path into the field — she was on the leading edge of women entering technology.

“It was a very male-dominated field, so I learned how to teach myself because the men wouldn’t tell me things,” Moore said. “And then a few years later, the internet exploded, so it made it easier to go find information.”

She credits her success to experiential learning, taking some classes here and there to fill in knowledge gaps, the confidence to try new things, and not fearing failure.

“My mother used to tell me all the time, ‘Nothing beats a failure but a try,'” Moore said.

She also described herself as a natural maker: “Probably as a result of the fact that we grew up poor,” she said. “Basically, if we wanted something and we couldn’t buy it, we made it. It started off with simple sewing. My first project, if you will, that I took on on my own was making a model of the heart for a science project, and I learned so much making that model of the heart that it stuck with me that when you make it with your hands, it helps you internalize what you’re learning.”

Moore’s leadership and philosophy landed the team a Rookie Inspiration Award their first year, other awards like Engineering Inspiration, and awards for different activities the team has done in the community. In 2012, through the nomination of students, Moore received the prestigious FRC Woodie Flowers Finalist Award (Woodie Flowers is a MIT professor and one of the founders of FRC). The FRC site describes the award as “based upon the team’s description of how the mentor inspired each member of the team in some or all the following ways:

- Level of student participation;

- Creativity of effort;

- Clear explanation of mathematical, scientific, and engineering concepts;

- Demonstration of enthusiasm for Science and Engineering;

- Encouragement to work on projects as a team effort;

- Inspiration to use problem-solving skills;

- Inspiration to become an effective communicator; and

- Motivation through communication.”

Her leadership drew the attention of other Chicago groups, including the Chicago Learning Exchange, a network of organizations focused on equity and hands-on innovative programs, especially in the out-of-school space.

“[These programs are] only made possible because there are extremely passionate people like Jackie,” said Sana Jafri, program officer at the Exchange.

Ultimately, Moore remained humble about her role as lead mentor of the Chicago Knights.

“There are lots of very motivated, very passionate, very smart people who don’t have the opportunities I’ve had,” Moore said. “And given those opportunities, they’d do even greater things.”

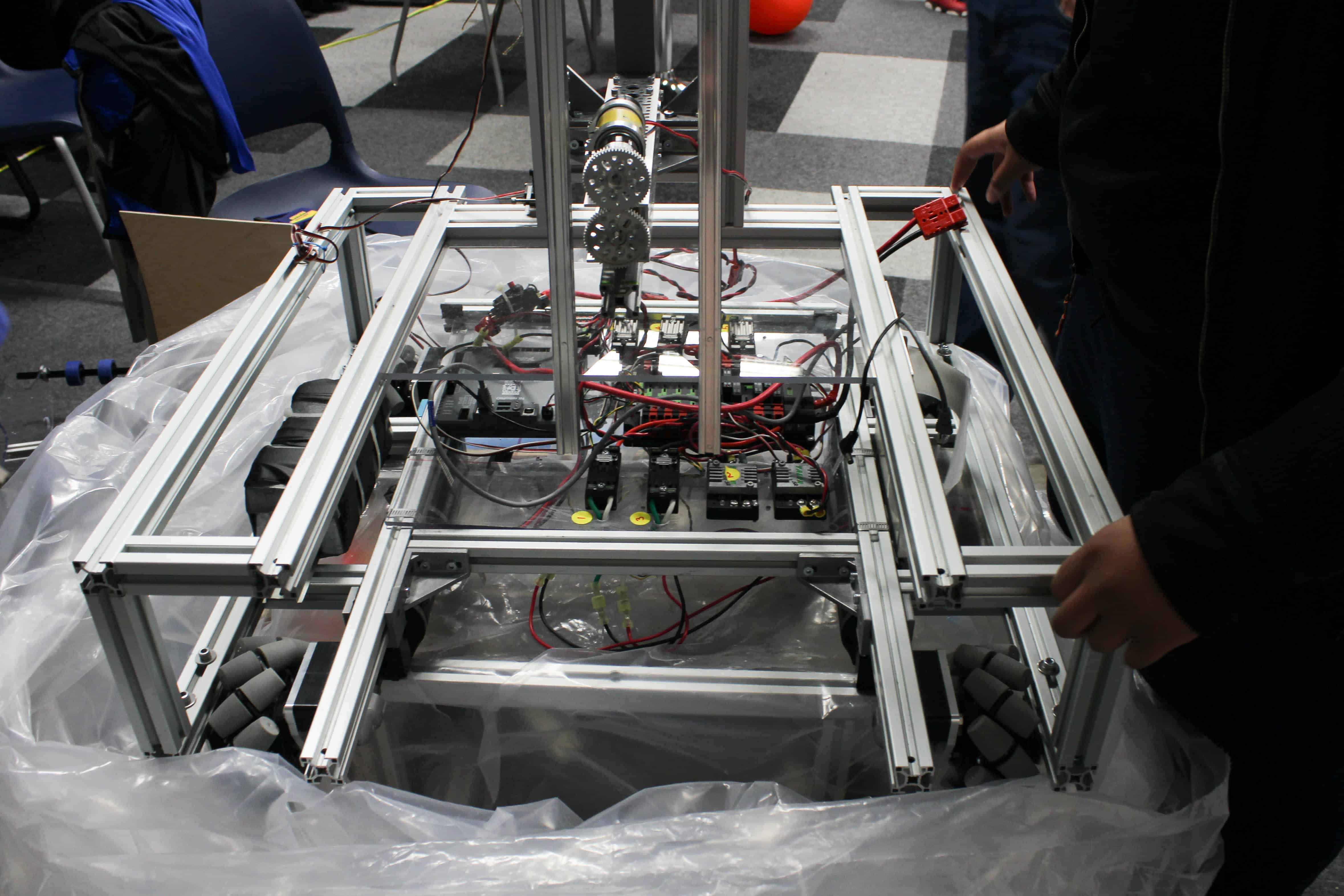

The FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC) isn’t the Battle Bots scenario that comes to mind for many. Competitions are based on a point and ranking system for the robot being able to complete tasks like placing a ball in a bin and being able to park a bot on stands of various heights. Through the formation of alliances during competition, three teams work together to strategize on how to block other teams from scoring points and the fastest way to complete point-scoring tasks during timed rounds.

In the Midwest Regional on March 7-9, the Knights came in 24th place out of 53 teams.

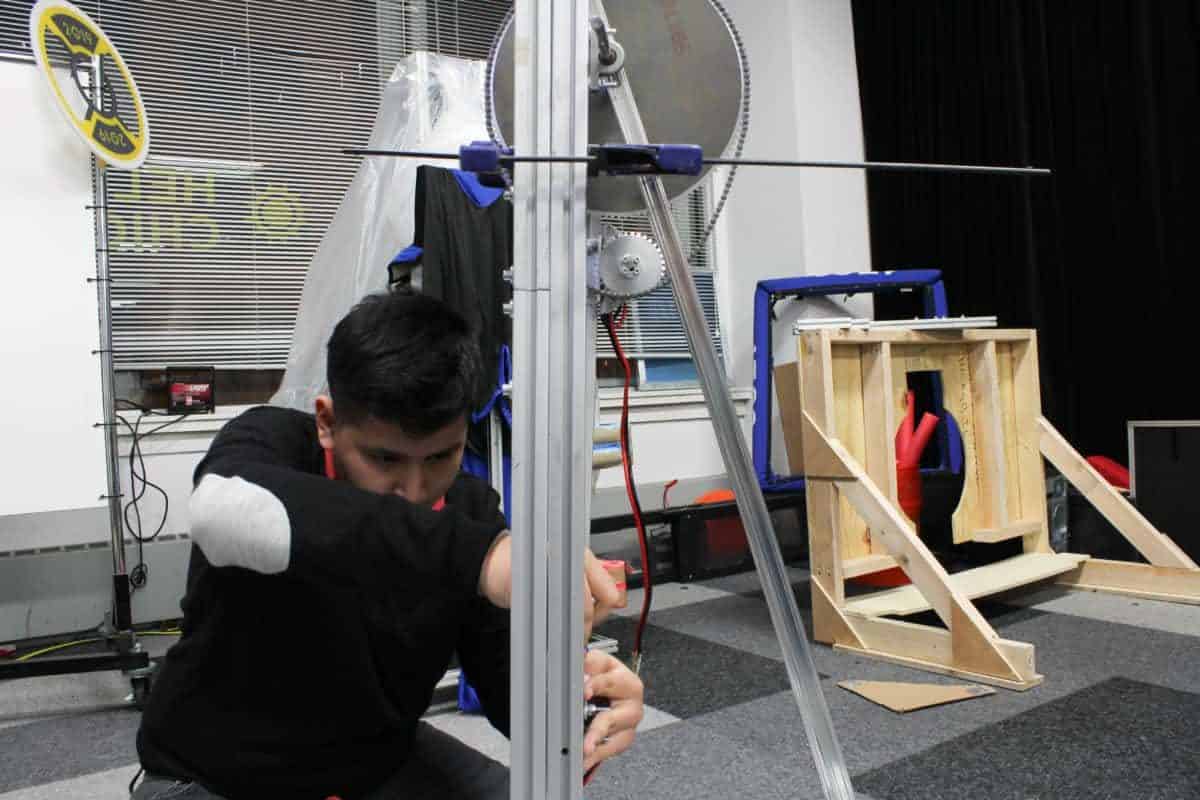

“Overall coming in 24th place out of 53 teams where many of the teams were powerhouse teams was actually pretty impressive,” Moore said, especially because the competition came with several challenges. At inspection, the team’s robot didn’t fit height requirements, coming in at half an inch too tall; the students had to disassemble and reassemble their robot on the same day.

“A big part of the event from my perspective as a leader is that those three days of the competition [are] when all the things you’ve learned kind of come together, because you have to — on the site, on the spot — solve problems,” Moore said.

The team this year was about a handful of students, smaller than in previous years and smaller than many other competing teams. Moore said one team next to them probably had 60 students, while other teams had less than 10.

“They were really concerned when they got there because their robot didn’t look as impressive as some others,” Moore said. “But then they realized how to look at it closely, to look past the powder coat, to look past the impressive looking kits, to look at the actual mechanisms.”

As it turned out, many of the well-resourced teams were having similar issues to the Knights, and Moore said that was affirming for the students. Financial resources are a big aspect of FRC competitions — it costs thousands of dollars to purchase a kit and to compete, which is a challenge especially for newer and under-resourced teams. Moore said the Midwest Regional was a $4,000 competition for their team and that the cost is one reason why the activity isn’t always as diverse as it should be.

Still, Moore said there was justification for the price.

“At the end of it, they’re better people,” Moore said. “So, yes, it’s expensive. Yes, it’s intense. But I think that an intense experience can benefit participants a lot more than something simple and easy, especially if it’s based on their interests. And robots allow students to explore so many interests, it’s unbelievable.”

Through competition, Powell said she has learned that the best robots are simple but effective.

“I feel like the best robot really stems from the team’s creativity and the way that their mind works,” she said. And she wasn’t discouraged by seeing other teams with more resources.

“We get to the competition and there are these huge robots with all these thousands of dollars worth of technology embedded in them,” Powell said. “Kids get on the field, and they don’t even know how to use it. They don’t know how to move anything. So what we do is we come up with the simplest techniques that get the job done, cost the least amount of money, but still does as well, if not better, than any of the robots out there.”

Yes — it’s a competition, but FRC is rooted in principles and coined terms like “gracious professionalism.” Explaining the phrase, Moore said: “It means that as a ‘gracious professional’ I will compete at an expert level, but I’ll be kind about it. I won’t destroy you to win, I’ll lift you up.”

This spirit of the competition is why Powell said one of the best parts of going to FRC is actually seeing everyone else’s ideas.

“We basically just take a note and save it for next time,” she said.

At the Midwest Regional, the learning was mutual. Other teams also took notes on the Knights’ robot — especially because they had created their own right angle gear box without precision machinery.

In the end, the teams not only learn from one another, they compete alongside one another in FRC alliances. At the beginning of a round, teams have five minutes to come together with their partners to decide on tactics.

“You’ve got to find a way to pull the best out of everybody in a very short time, and you don’t have time to say, ‘I don’t like your politics. I don’t like the way you dress. I think your skin color’s appalling.’ — you don’t have time for that stuff,” Moore laughed.

“So what happens instead? They focus on the problem. And you do that enough times, after awhile you think, ‘You know, we can focus on a common problem. We can focus on a common goal.'”

Through competing, Moore said she saw many of her first-time students open up, especially during the process of explaining their robots to judges.

“The students really earn their knowledge,” she said. “They own their learning.”

This process, she said, is not only a confidence boost — it leaves students with the feeling that they deserve to be a part of the competition.

“It’s also an opportunity for them to understand that they belong, and I can’t stress enough the need for young people to feel they belong,” Moore said. “When you feel that you’re outclassed and therefore you shouldn’t be there, often you don’t try.”

After the competition, Moore said she considered the event a success because everyone grew and walked away with higher opinions of themselves and of their robot than when they walked in. They also left eager for more competition. Seeing the outcome of the students’ success not only meant a lot to Moore as a mentor, but also to parents of team members.

“Working with people, learning to work with different personalities, learning to work with your hands, having some confidence, being sure about yourself and about the decisions that you make [or] decisions that the team makes, learning to follow leadership even if it’s from a peer,” Dorsey Smith said of her sons, “I would hope that all of these would factor into their growth as human beings, as employees, as husbands, as fathers.”

Corrections: A previous edition of this post incorrectly referred to the X-Carve machine (pictured) as a 3D printer. It is a CNC machine. A photo was also previously credited to Josh Moore. The photo is courtesy of John Moore.

Note: This is second of two stories for EdNC based on my trip to Chicago in March. The first story was on Project SYNCERE. Stay tuned for more on robotics with a recap of the FRC state championships in NC coming next week.