Last week was National School Choice, a week intended as a “celebration of opportunity in education” across the country. However, as the public has grown increasingly divided politically on this issue, the week also serves as a time for critics of school choice to voice their opposition.

As my colleague Alex Granados explained in his column last Monday, school choice is a broad term that can mean many different things. Traditional public school districts offer school choice in the form of magnet schools, early colleges, and alternative schools, among others. Generally though, when talking about school choice in North Carolina, we are talking about three things: charter schools, the opportunity scholarship program, and the Education Savings Account program. In this article, we will focus on charter schools, as they represent the largest vehicle of school choice for students and families in North Carolina.

Charter schools at a glance

Charter schools are public schools that are publicly funded but privately operated. Individuals, groups, and both for-profit and non-profit organizations can apply to open and operate a charter school. According to the latest numbers from the Office of Charter Schools at the Department of Public Instruction (DPI), there are 184 charter schools currently operating in North Carolina enrolling more than 109,000 students, or 7.3 percent of the state’s public school enrollment. An additional 22 charters are currently in the year-long planning process.

The name “charter school” comes from the fact that the schools operate under terms outlined in their charter, which serves as a contract between the school and the charter authorizing body. In North Carolina, the State Board of Education serves as the charter authorizing body, determining which charters are allowed to open, which are renewed, and which are closed based on recommendations from the Charter School Advisory Board.

Charter schools are granted freedom from many of the rules and regulations imposed on traditional public schools. Different states have different laws governing charters, but largely charters have flexibility in how they spend their budget, who they hire and how they staff the school, what curriculum they use, and how long the school day and school year should be, among other things. In North Carolina, only 50 percent of teachers at a charter school are required to be licensed.

Charter school students are required to take state tests, and charters must file a report every year with the State Board of Education detailing student outcomes. In states with the strongest charter laws, such as Massachusetts and Louisiana, charters that do not meet the benchmarks outlined in their contract for student performance are closed. In North Carolina, continually low-performing schools are required to appear before the Charter School Advisory Board. Since 2012, only four charter schools have been closed due to low academic performance. Of the 46 charters that have closed since 1996, 35 (80 percent) have closed due to financial reasons.

A look back

North Carolina established charter schools in 1996 (N.C. General Statute § 115C-218). The law represented a bipartisan compromise at the time, with Democrats agreeing to vote for charter schools as a way to avoid their bigger concern, vouchers for private school. The legislation passed the House 78-25 and the Senate 37-8. The purpose of establishing charter schools is laid out in the legislation:

- Improve student learning;

- Increase learning opportunities for all students, with special emphasis on expanded learning experiences for students who are identified as at risk of academic failure or academically gifted;

- Encourage the use of different and innovative teaching methods;

- Create new professional opportunities for teachers, including the opportunities to be responsible for the learning program at the school site;

- Provide parents and students with expanded choices in the types of educational opportunities that are available within the public school system; and

- Hold the schools established under this part accountable for meeting measurable student achievement results, and provide the schools with a method to change from rule-based to performance-based accountability systems.

At the time, the law capped the number of charter schools at 100, which was reached in 2001. From 2001 to 2011, charter advocates lobbied to increase the cap, but it wasn’t lifted until Republicans gained control of the legislature and passed legislation removing the charter cap in 2011. Since then, the number of charter schools has increased every year resulting in the 184 schools operating today, although not at the pace some opponents feared. Additionally, North Carolina now has two virtual charter schools, NC Connections Academy and NC Virtual Charter, which were approved by the State Board in 2015 for a four-year pilot.

Of the 43 states and the District of Columbia that have laws allowing charter schools, 10 states had more charter schools than North Carolina in the 2017-2018 school year, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. California and Texas had the most charters at 1,275 and 774, respectively, followed by Florida and Arizona at 661 and 556. Nine states have more students in charter schools than North Carolina.

How are charter schools performing?

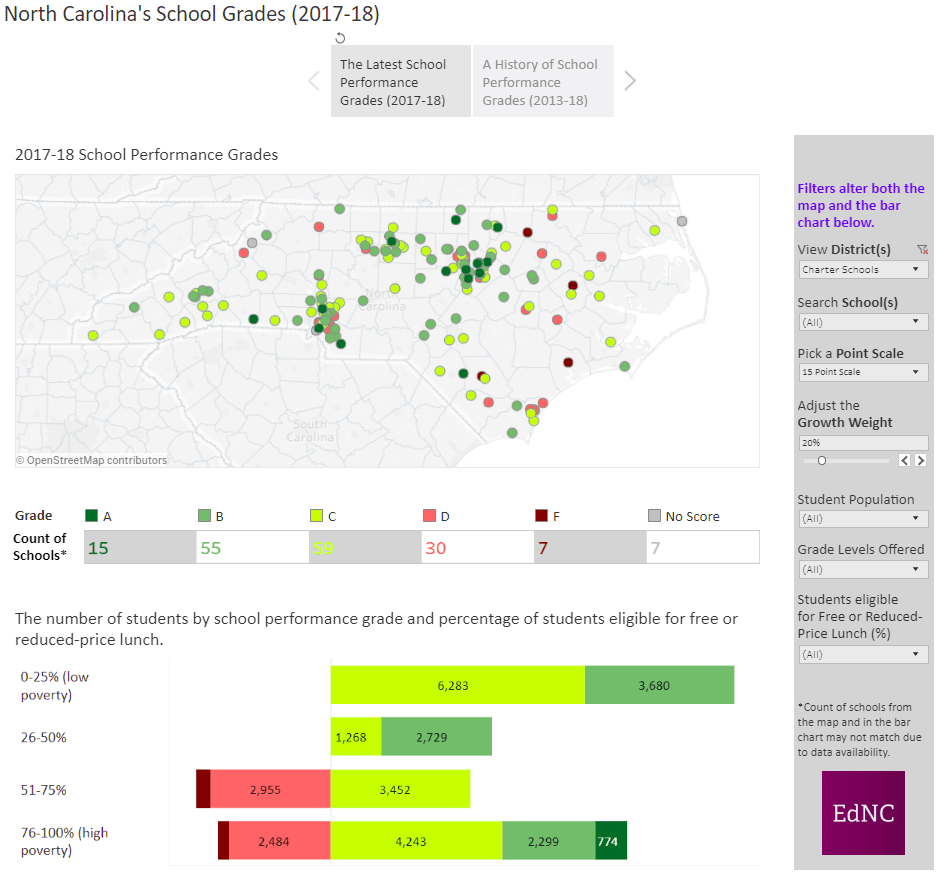

In the map below, created by Emily Antozsyk from the Friday Institute for EducationNC’s Consider It Mapped series, you can see the latest school performance grades for every public school in North Carolina (if the map is not showing up, view it here). To view the 2017-2018 performance grades of North Carolina’s charter schools, click on the “View District” drop down menu, click on “All,” and then select “Charter Schools” from the districts. Once you have only charter schools selected, click “Apply” to show the charter schools on the map. As you hover over each dot, you will see the name of the charter school along with the school performance grade.

When you filter for charter schools, you can see that 15 earned a school performance grade of A in the 2017-2018 school year, 55 earned a B, 59 earned a C, 30 earned a D, 7 earned an F, and 7 did not receive a score. In the bar chart below the map, you can see the number of students by the letter grade their school earned. The chart is divided by percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRL) at each school. For example, you can see that of charter schools where 76 to 100 percent of students qualify for FRL, 274 students attend a school that earned an F; 2,484 students attend a school that received a D; 4,243 attend a school that received a C; 2,229 attend a school that received a B; and 774 attend a school that received an A.

The map allows you to filter by school population, grade levels offered, and percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. You can also adjust the growth weight. As a reminder, school performance grades are currently calculated using a combination of academic achievement — measured by test scores, graduation rates, and measures of work readiness — and growth, measured by whether or not students met expected growth that year. The current formula is based on 80 percent academic achievement and 20 percent growth, but you can adjust those weights in the map to see how the performance scores would look if student growth was weighted differently.

What does the research say?

The question everyone really wants to know is how are charter schools doing relative to traditional public schools, but this question is more complicated than it seems. As education researchers can tell you, it is not as simple as comparing student test scores or other performance indicators at charter schools versus traditional schools. In many cases, charter school students may differ from traditional public school students in ways that have an impact on their outcomes; they may be of a different socioeconomic status, race or ethnicity, or, as some argue, their parents may be more actively involved in their education. To compare the two groups of students and accurately understand the impact of attending a charter school versus a traditional public school, you need to effectively remove those differences so you are comparing apples to apples instead of apples to oranges.

The gold standard in research is the randomized control trial, where two identical groups are randomly given different treatments and their outcomes are compared. However, while you can do this in a medical trial, it is more difficult to do with students. Education researchers often use what is called a quasi-experimental research design for studies, which is a design that mimics the randomized control trial design as best as possible.

Researchers at Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) produced a national study of charter schools utilizing a quasi-experimental research design where they created “virtual twins” for charter students based on traditional public school students with similar characteristics and test scores. Their 2013 National Charter School Study examined charter school outcomes in 27 states and found, “On average, students attending charter schools have eight additional days of learning in reading and the same days of learning in math per year compared to their peers in traditional public schools.” The authors are not saying that charter school students are in school longer (although they may be in some cases), but rather that the increase in student learning is equivalent to additional days of learning. In 2015, they published a study of urban charter schools and found that students attending charter schools gained an additional 40 days of learning per year in math and 28 days of learning per year in reading.

While this pair of studies provide evidence nationally in how charter schools are doing, they do not tell us specifically how charters are doing compared to traditional public schools in North Carolina. The Center published a lengthy report on charter schools in 2002 and then again in 2007, concluding in the 2007 report that “charters come up short” based on evaluations of student performance data. Since then, the state has changed both the state tests and the evaluation framework, so comparing student outcomes between the two periods is difficult. However, it appears that charters are slowly improving.

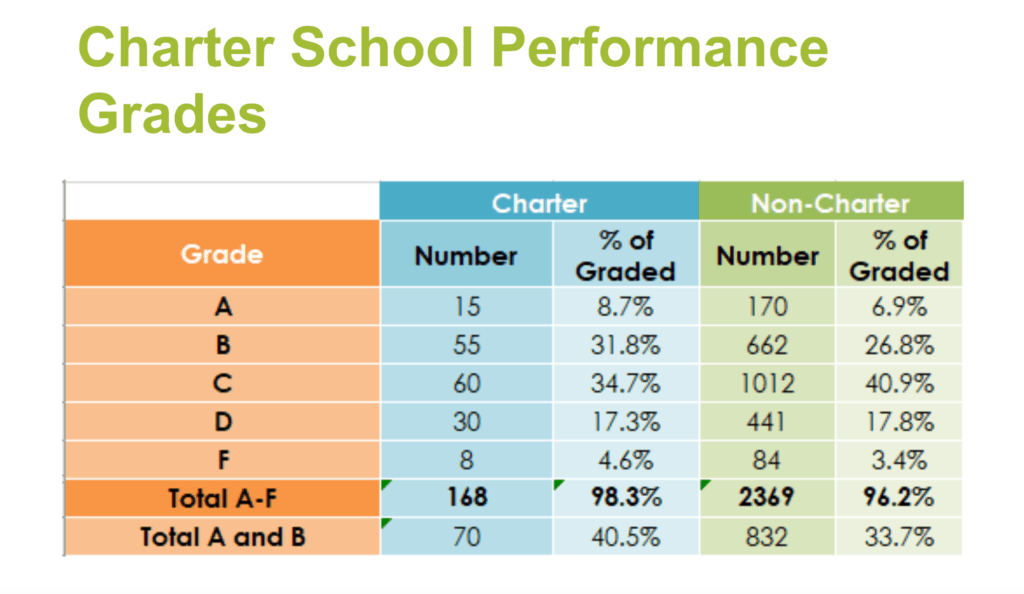

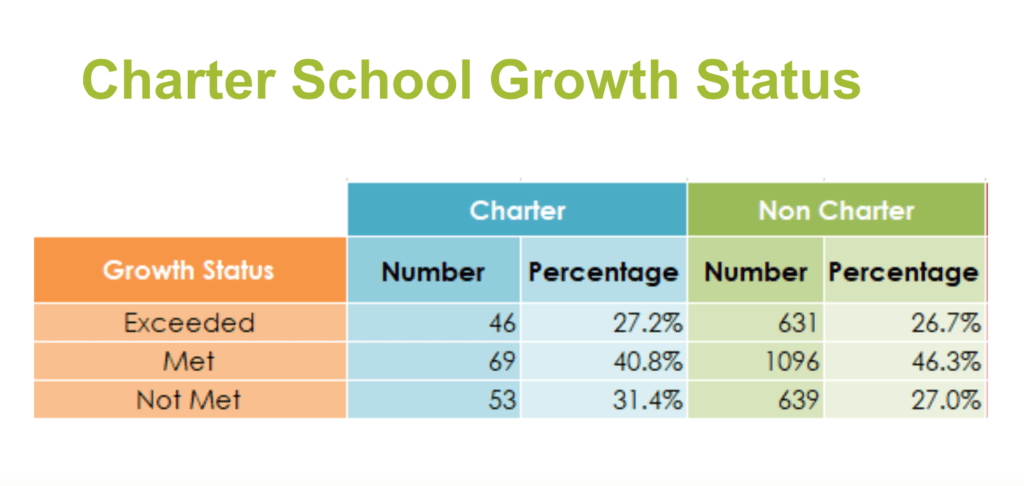

According to the Office of Charter Schools’ latest report, the number of charter schools receiving a D or F declined this year for the fifth consecutive year and the number exceeding growth rose from 36 to 46 this past year. While the share of charter schools receiving an A or B is higher than traditional public schools (40.5 percent compared to 33.7 percent), the share receiving an F is also higher than traditional public schools (4.6 percent to 3.4 percent). Looking at growth, a higher share of traditional public schools exceeded or met growth (73 percent) than charter schools (68 percent).

While these numbers give us something to go on, it is still hard to objectively compare the two groups. One reason is the growing number of charters serving a higher proportion of white students. In both the 2002 and 2007 report, the Center stated that charter schools were more racially segregated than traditional public schools. From the 2007 report: “In 2005-06, 39 of 99 charter schools had more than a 50 percent minority student population. Twenty-six of these schools were 80 percent or more non-white, and 14 of those were more than 95 percent African American.”

In the years since this report, several of those schools serving a majority of African American students have closed while more schools serving a higher proportion of white students have opened. A 2015 study from the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research stated, “Where there was once a sector that included many heavily-minority schools, the charter school sector in North Carolina has over time become one that includes many more schools with relatively high percentages of white students.”

While the legislation establishing charter schools states that within one year of opening, the student population should “reasonably reflect the racial and ethnic composition of the general population,” in practice only four charter schools target a more diverse student body population through admissions (as of February 2018): Central Park School for Children in Durham County, Community School of Davidson in Mecklenburg County, GLOW Academy in New Hanover County, and Charlotte Lab School.

Further complicating the issue is House Bill 514, a law allowing the creation of municipal charter schools that passed in the 2018 legislative session. Critics argue that this will allow whiter, more affluent towns to create their own charters, removing their students from the larger county districts and contributing to resegregation.

North Carolinians weigh in

From January 21 to January 25, 2019, Reach NC Voices asked North Carolinians if they support or oppose charter schools. Here’s what they said.

Here are a sample of their responses:

“With properly designed schools and more flexible legislation, choice can exist even within the public school system that still allows for oversight.”

“School choice and charter schools are two separate issues entirely. Most people don’t understand the choice options with in their own district. Families should always have a second option to what is their prescribed base school for a multitude of personal and educational reasons.”

“Charter schools are wonderful options. They have small boards that make the best decisions for their students. They are able to cut through much of the bureaucracy and politics of large school districts. We can keep saying that the emphasis should be improving traditional school districts, but we have been saying that for decades and they still have problems that many charters have corrected.”

“Charters are great in theory but lead to resegregation and increase the disparity of educational resources available to low income urban and rural students.”

“I worry about the proliferation of charter schools without [what] seems like needed oversight. School choice is a good thing in theory, but in practice I worry about the impact unabated growth of charters have on traditional public schools budgets and ability to operate.”

“I am a NC Teaching Fellow and I work in an NC charter school. I had no intention of teaching in a charter school in college, but a job was presented to me and I took it. I love my school and plan to stay. My school is extremely diverse, so what I see is that our school does not increase degegregation, though I imagine there are schools that do. This is an important angle to me on the charter school debate. It’s also important to me that charter schools that are run for profit (which my school is not) are not lumped in with schools that are run independently in this discussion, as well as programs that take money from public schools to give to private schools. These three school choice options are not created equal, and need to be evaluated separately.”

Looking forward

The National Alliance of Public Charter Schools ranks North Carolina’s charter laws 14th in the country out of 44. Areas where North Carolina loses points in their ranking system include equitable access to capital funding, accountability of virtual charters, clear identification of special education requirements, and transparency around education service providers. They recommend fixing these areas, stating, “Potential areas of improvement include ensuring equitable operational funding and equitable access to capital funding and facilities, providing adequate authorizer funding, ensuring transparency regarding educational service providers, and strengthening accountability for full-time virtual charter schools.”

In 2015, EducationNC and NCCPPR CEO Mebane Rash wrote on the 20th anniversary of charter school legislation, “With the 20th anniversary of charters just ahead, it is time for us as a state to identify charter innovations and think about how to scale them to our public school setting to drive change. And we need to wrestle with what happens with low performing charter and traditional public schools.” Both statements remain true today, almost four years later. As the legislature enters the 2019 legislative session, both proponents and critics of charters are watching to see if they will make any changes to strengthen accountability, deal with the impact of charters on segregation of schools, and more. At the Center and EdNC, we will continue to ask these questions about the future of charter schools in North Carolina:

- What are best practices from charters over the past two decades, and how do we scale them?

- What innovations in practice and management are needed and how do we incentivize them?

- Who is responsible for sharing information about best practices with public school administrators and educators, parents, and policymakers? If charter principals were expected to serve that function, they have a school to run. If not them, then who?

- Have we done a good job of enabling charters and districts to work together? Has that been done elsewhere? If so, how do we replicate that across the state?

- How prepared are we as a state for the continued rise in percentages of rural students attending charters?

- As the number of charters continue to grow as a percentage of market share, what changes on the horizon might we be able to plan for and anticipate using the examples of places like Philadelphia, Milwaukee, and New Orleans as guides?

- Our state has never clearly identified our expectations for charter school performance. How good is good enough?

- What questions do you think we should be asking about North Carolina’s charter school experience? Who has a story to tell that has not been told?

Correction: A previous edition of this post incorrectly stated the 2013 CREDO study utilized charter school lottery results. Researchers actually used a virtual control record (VCR) approach that creates a “virtual twin” for charter students.