David Shockley did not have the typical path to the community college presidency. As a teenager and in college, he worked in construction, building houses, putting on roofs, and working with a brick mason. After college, he entered the higher education world and held several roles, including in facilities and maintenance, information technology, student services, and marketing.

At Appalachian State University, Shockley was responsible for purchasing and bids. After moving to Caldwell Community College at age 26, he eventually became the vice president of students and later the executive vice president, where he ran the internal institution day-to-day for five years under the direction of then-president Ken Boham.

Now the president at Surry Community College, a position he’s held since 2012, Shockley is one of the longest serving presidents in the North Carolina Community College System. He believes all of his experiences, down to his work in construction, have prepared him to be an effective president.

“I can honestly tell you there is no part of this institution that I don’t have boots on the ground experience in,” Shockley said. “To me, I think that is huge.”

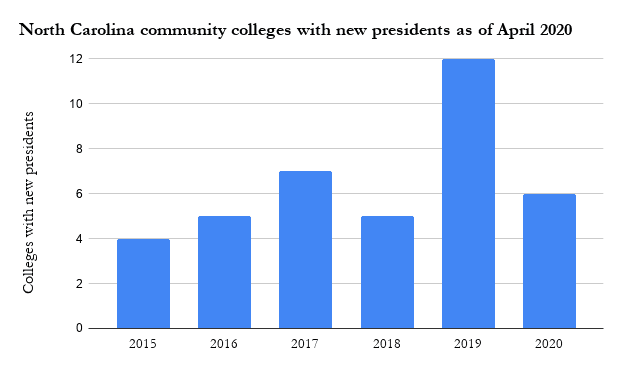

In 2019, new presidents started serving at 12 of the 58 community colleges in North Carolina. So far this year, one new president started in January at Haywood Community College (Shelley White), five new presidents have been approved by the State Board of Community Colleges, and four colleges are in the middle of presidential searches — all happening in the midst of a pandemic.

Since 2015, 39 of the 58 community colleges in North Carolina have experienced presidential turnover or will this year, and four more have active presidential searches.

Six of these 39 new presidents had served as president elsewhere, either at another community college in North Carolina or out-of-state. However, the other 33 are truly new presidents, coming into the job for the first time.

Rise in presidential turnover is a national phenomenon

Increasing rates of presidential turnover are not unique to North Carolina. Researchers and community college stakeholders have been sounding the alarm on this issue for the past decade. In 2015, the American Association of Community Colleges conducted a national survey of 239 community college presidents, 80% of whom said they were planning to retire within 10 years.

“We baby boomers are now getting to be retirement age, and we realize it’s time to do something else,” said Bill Ingram, president of Durham Technical Community College, who is set to retire this year.

In addition to the wave of retirements, presidents are also staying in their jobs for less time than they have in the past.

“At one time, presidential tenure was seven to nine years, then six to seven, now it’s five to seven years,” said Audrey Jaeger, executive director of the Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research. “Retirements have exacerbated that issue,” Jaeger continued. “North Carolina is almost the model for the country in how dramatic that shift can be.”

There are many factors contributing to the decline in presidential tenure, but over the course of several interviews and a survey of North Carolina’s community college presidents, one thing became increasingly clear: the job is simply more challenging now than it used to be.

“These jobs have become much more challenging,” said Patricia Skinner, former president of Gaston Community College, who retired in March after more than 25 years on the job. “It’s a 24/7 job, and with technology you are never away. It’s a commitment.”

Jaeger agreed. “It’s a more difficult role than it used to be … with politics, with social media, with resources declining. It’s just a really difficult job, more than it has ever been,” she said. “For community colleges, their job is even more difficult because they’re not as resourced as their university partners, and they are serving populations that are underserved and have more needs.”

Community college president: A difficult job

Several changes have contributed to making the role of a community college president more difficult, but the big themes that emerged from interviews and a survey of North Carolina community college presidents are: 1) budgetary pressures due to fewer financial resources; 2) changing student demographics; 3) an increasingly polarized political climate; and 4) increasing safety and student mental health concerns.

Budgetary pressures

North Carolina’s community colleges receive the majority of their funding from state appropriations. As past research from EdNC has shown, of every $100 in revenue the community college system received in fiscal year 2015-16, $57 came from state appropriations, $19 from tuition receipts, $13 from local governments, and $11 from other sources.

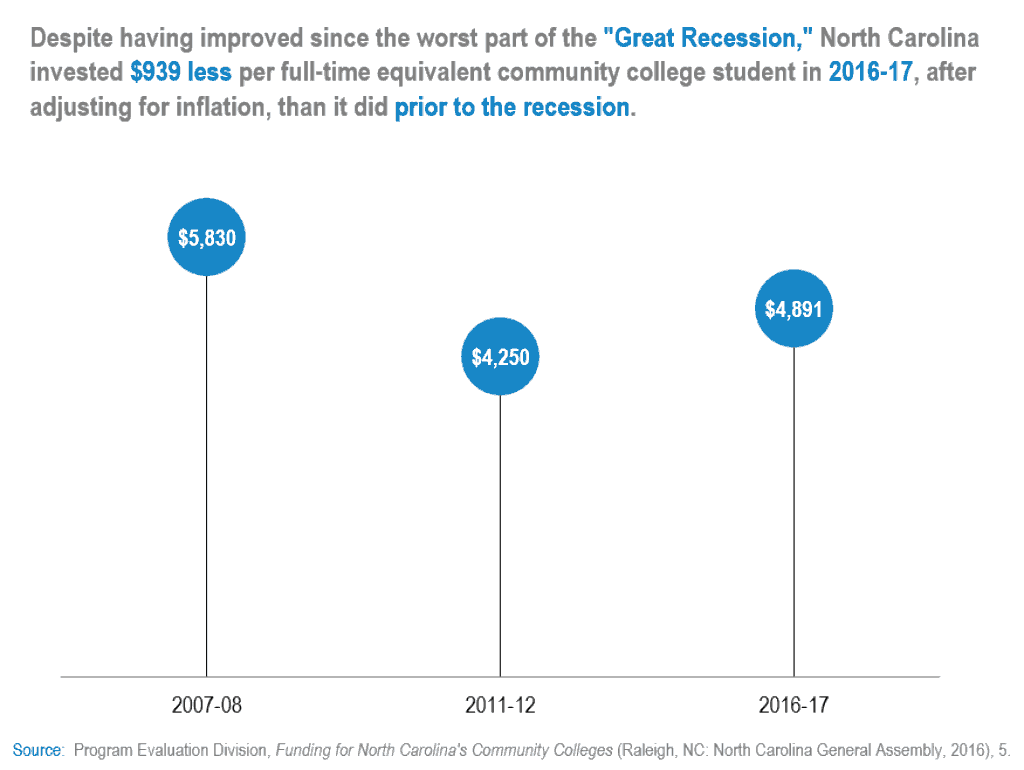

Following the Great Recession and the resulting drop in tax revenues, North Carolina cut state appropriations for community colleges. From 2007-08 to 2016-17, inflation-adjusted state support dropped from $5,830 per full-time equivalent student to $4,891.

“States disinvested heavily in community colleges and higher education as a whole,” said Josh Wyner, executive director of Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program. “It’s come back some,” Wyner continued, “but we are expecting unfortunately to see a shift now,” due to the economic impact of COVID-19.

“Colleges will have to figure out how to do the same or more with less resources from the state,” he said.

At the same time, until this past year, enrollment has been on the decline at North Carolina’s community colleges after a surge during the Great Recession. Because the majority of state funding is allocated to community colleges based on enrollment, declining enrollment leads to less funding. The combination of less state support and years of declining enrollment has created intense budgetary pressures for many colleges.

“The job has changed,” Shockley said. “A large part of it is the downturn that happened in 2008 turned everything upside down with our financing model, so all of a sudden it’s a lot of pressure.”

Fewer dollars year after year mean presidents are forced to make tough decisions, including letting faculty and staff go.

“Many schools have suffered seven or eight years of economic loss, financial loss, and their enrollments have dropped 40% in some cases,” Shockley said. “It weighs on you when you’re constantly sending people home, and you’re constantly cutting and cutting and cutting.”

A respondent to the community college president survey summed up the impact of these budgetary pressures:

“Dealing with poor budgets due to declining enrollments is causing presidents to reevaluate their decision to become a president. We all became presidents to grow our institutions and serve students needs better. With very poor budgets over the last few years this has become either impossible or very difficult.”

Declining financial resources have led colleges to rely much more on fundraising and grant writing. One survey respondent said, “Poor funding leads us to pursue grants that make work for our staff too hard…As a consequence we end up hiring too many bureaucrats and not enough English, Math, and Nursing faculty.”

Several presidents commented on the importance of being skilled fundraisers. One survey respondent said, “Our role in fundraising has increased but our skillset has not. Many of us are not good at it because we’ve never done it before.”

Changing student demographics

As previous EdNC research noted, community colleges are the main provider of postsecondary education for many North Carolinians thanks to their relatively low tuition and open door policy. As the state’s population has grown more diverse over the past few decades, so has North Carolina’s community college student population. According to data from the Southern Regional Education Board, in 2017, North Carolina community colleges enrolled 45% of the state’s black degree-seeking students and 53% of its Hispanic degree-seeking students.

Community colleges also enroll a higher share of low socioeconomic students than four-year institutions. A 2016 Program Evaluation Division report stated, “The disproportionate amount of at-risk students that community colleges serve in the higher education system is stark compared to four-year institutions.” At community colleges, low socioeconomic status students outnumber high socioeconomic status students two to one.

Finally, the growth of dual enrollment in North Carolina has meant that community colleges are now serving a greater share of high school students than ever before. A 2018 report to the General Assembly stated dual enrollment has been steadily increasing since 2012-13. In 2017, 60.7% of graduating high school students earned college credit before graduating.

“Our student body is much younger now than it was 10 years ago as we see more and more high school students dual enrolled,” said Ingram. “Right now, maybe 800 of our 5,000 students or more are high school students. That number is growing for us, and for some others that number is a lot bigger.”

Ingram, whose college serves high school students from three different school districts, explains some of the challenges associated with this growing population:

“We have three different school systems. We have an urban minority-majority school system, we have what would qualify as a suburban school system that many consider the best in the state in terms of SAT scores and college-going rates, and then we have a largely rural school system. We’re serving three different school systems with three different demographic profiles for students, and three different sets of academic and educational needs and desires.”

He continued, “Whose discipline policies are going to be in place? Who’s going to decide what the grading policies are? Who’s going to manage the parents angry with the teacher because the student got a grade they think is unfair? On a college campus, parents are not involved in the conversation.”

All of these extra considerations require a different skill set, almost like being a high school principal in some ways, Ingram said. And community college presidents need to have strong negotiation and collaboration skills to work with their K-12 partners.

Polarized political climate

Several presidents brought up the increasingly polarized political climate as one of the major challenges in their roles. As national, state, and local politics have become more partisan, community college presidents are stuck in the middle, dealing with political differences at both the state level as they lobby to get more resources and at the local level on their boards of trustees.

“The state politics has really gotten me worn out,” said Ingram. “We are everyone’s friend until it comes to passing a budget. We have to fight and scrap for every dollar we get.”

Last year’s legislative session is an example of how political polarization has negatively impacted the colleges. The budget passed by the legislature last year was a resounding win for the community college system. Almost all of their legislative priorities were funded, including fully funding short-term workforce programs, their number one priority.

However, because the Republican-controlled legislature and Democratic governor could not work out a compromise, Gov. Cooper vetoed the budget, and the legislature was unable to override the veto. To get around the governor’s veto, the legislature passed a series of mini-budget bills. The majority of the community college system’s priorities passed and were signed into law by the governor. However, the governor vetoed the bill that included money for salary increases for community college personnel. As we examined in our faculty pay series, the consequences of not passing that bill are severe — North Carolina community college faculty are some of the lowest paid in the country.

“It’s disheartening to [our faculty] to see their financial needs ignored by both legislative leaders and executive leaders who talk about how wonderful the system is and how important their work is,” said Ingram.

The political environment can also have a large impact on colleges through the politicization of their boards of trustees. Wyner explained how he sees this impact on colleges:

“People come onto community college boards with specific ideas about tax rates and other issues with regards to what colleges should offer … If somebody who comes in, who’s a rogue trustee who really doesn’t have students at heart but has a political agenda at the center of the reason why they’re serving, they can do damage if your board doesn’t have a strong center of understanding of why they’re doing what they’re doing.”

Survey respondents agreed. One president said, “The political climate is brutal. Presidents are used as political pawns for boards of trustees, which can turn over quickly.”

Another stated, “Politics plays a big factor in the length of any [president’s] decision to stay or leave … A board and president who have healthy communication and understand their roles and responsibilities are much more likely to have a harmonious relationship, leading to less turnover in the presidency.”

Safety and mental health concerns

The final theme that emerged was the increase in student mental health issues and the need to secure campuses against active shooters and others seeking to do harm to students and community college personnel.

In January, EdNC interviewed outgoing Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College President Dennis King and asked him what keeps him up at night. He responded, “One thing really keeps me up at night and that would be an armed intruder — someone who could come in and do what has been done at so many other places in our country and at so many other times.”

Skinner also cited campus safety as something that has changed in her time as president. “Just think about the safety issues,” she said. “We didn’t have to worry about that in the early days.”

As a reflection of this change, the North Carolina Association of Community College Presidents recently added a new standing committee on mental health and campus safety.

“I’m dealing with so many mental health issues and campus safety issues,” Shockley said, “… [including] students who are making threats of doing harm to themselves and other students, faculty and staff, and me personally.”

The best job in the world

All of these factors combine to make the position of community college president particularly stressful and contribute to the shortening of presidential tenure.

One president summed up the multiple factors contributing to the wave of new presidents North Carolina has seen in recent years:

“I don’t think there is any one single reason. Institutions are now mature. The first wave of founding presidents, presidents serving long tenures, have left the stage. We see a significant number of presidents moving into the state after years of service in their native state. My guess is these tenures are capstone experiences for many and were never intended to be lengthy. But there are other reasons that have more clearly emerged over the last few years. For many schools enrollments have fallen. Budgets are challenging. Salaries remain flat and often uncompetitive. Expectations for leadership are often unrealistic. Much of many presidents’ time has been spent trying to shore up flagging programs or to reduce or restructure faculty contracts. No one wants to be a president to lead retrenchments. For those that have been assigned these responsibilities, I note that their length of service is fairly short. If you’re not from the rural areas that many of these colleges serve, the incentive to own the challenges facing the institution and the service area are probably less. Many presidents move on after they reach an understanding that they cannot impact the institution. I feel certain that leading urban campuses have their own challenges. But, note, so many of North Carolina’s community colleges serve rural areas that are facing population decline or the dislocation of industry. This is the environment many must confront in their role as a president. And, as always, shorter tenures avoid contract issues. Sometimes it’s easier to move on than it is to endure political uncertainties.”

And yet, every president I spoke with and many who responded to the survey highlighted the joy they find in their positions from seeing students succeed.

“It can be the best job in the world,” Skinner said. “When I see those students walking across the stage, or I hear stories of people that have been successful, that is the real joy of the job that you can really make a difference.”

Shockley agreed. “When our students are successful and we change lives,” he said, “there’s nothing better than that.”

And despite all of the challenges community colleges face today, Ingram believes their moment has come.

“I think that this is community colleges’ time. That we finally have turned the corner in terms of articulating our place in the education spectrum in the United States. We are ready to step up to help solve the challenges that our communities face to keep talented people getting into the workplace to provide economic equity and mobility.”

Recommended reading