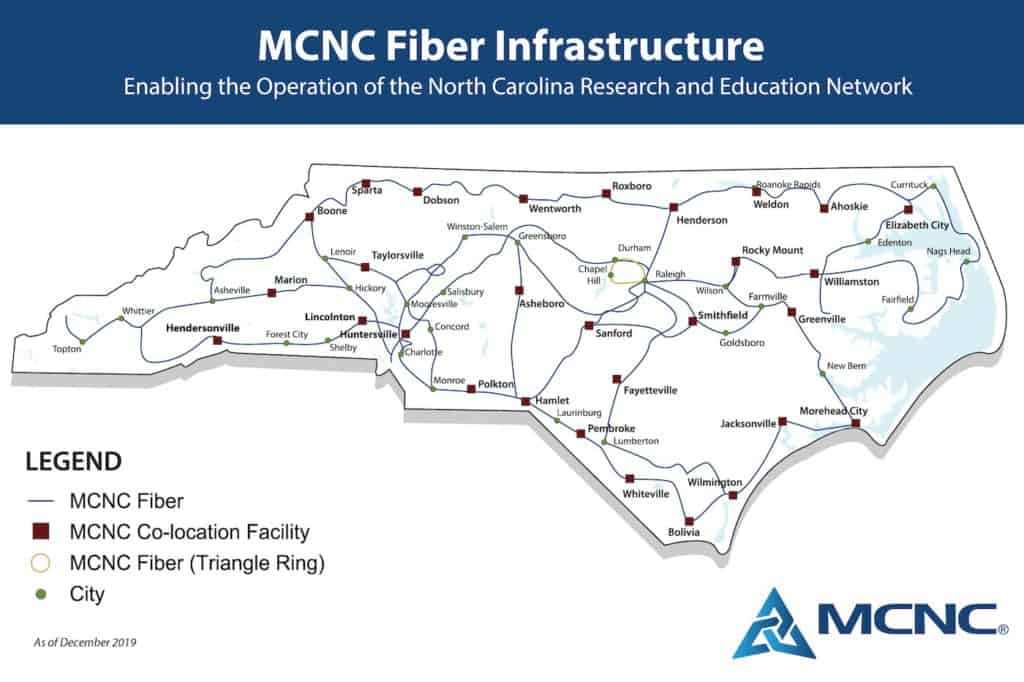

If you don’t know about MCNC, CEO Jean Davis says to “just think of us as Google Fiber for the public sector.” A 40-year-old nonprofit organization, MCNC began as a technology incubator that has morphed into a statewide broadband internet network. Today, MCNC owns, builds, and operates the North Carolina Research and Education Network (NCREN), which consists of more than 4,000 miles of fiber optic infrastructure.

Davis describes MCNC’s network as a “middle mile backbone” that provides internet to 1,070 anchor institutions in the state, including K-12 schools, community colleges, universities, research institutions, nonprofit health care companies, public safety facilities, and libraries.

“Think of our network as the interstate highway – the big roads that go all over the state. From there, local roads get built off to serve the communities,” Davis said. “For example, when it comes to K-12, we have high-speed fiber into all 115 school districts. From there, the local school district makes their own decisions about how they connect the schools.”

MCNC owns physical fiber in 90 of the state’s 100 counties, with additional fiber that the organization has leased or swapped with other companies in the remaining 10. In collaboration with the state Department of Instruction and the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation under the School Connectivity Initiative, Davis said MCNC now has fiber to almost 100% of the state’s K-12 schools.

When it comes to ensuring digital equity for all North Carolina students within their physical school buildings, Davis says we are in great shape — but the problem lies in rural residential connectivity, an issue that’s been exacerbated as school buildings and other anchor institutions remain closed due to COVID-19.

Broadband internet issues are often talked about in terms of three A’s: access, affordability, and adoption. Rural areas are sparsely populated, making it more difficult for companies to get a return on their investment of building fiber or other technical systems. That leaves some rural communities with one or no broadband internet providers. Then there are the adoption and affordability issues – people may not see a need for a high-speed internet connection, or, more likely, aren’t able to afford the cost.

The result?

“Rural students are left behind,” Davis said.

Fiber 101

– Fiber: Fiber optic internet transfers information by sending a beam of light through fiber optic glass cables. Fiber cables consist of many smaller optical fibers, which consist of two parts: the core, where the light passes through, and the cladding, a thicker layer wrapped around the core. Fiber currently provides the fastest internet speeds available — up to 1 GB or 1,000 MB.

Broadband infrastructure consists of the backbone, the middle mile, and the last mile.

– Backbone: The backbone consists of multiple fiber-optic lines capable of transmitting large amounts of data. It provides a path for the exchange of information that local or regional networks can connect with for long-distance data transmission. MCNC’s backbone is called the North Carolina Research and Education Network (NCREN).

– Middle mile: This middle stretch of fiber links the backbone with a core network, and in the case of MCNC, with anchor institutions like K-12 school districts, community colleges, and more.

– Last mile: This final stretch of fiber connects residential homes and small businesses to the network. There are different types of last mile connections, including fiber to the street, where fiber is delivered to a central street cabinet and then dispersed by copper cables, and fiber to the home, where direct fiber lines are provided to the residence.

Looking toward solutions

Leveraging MCNC’s network

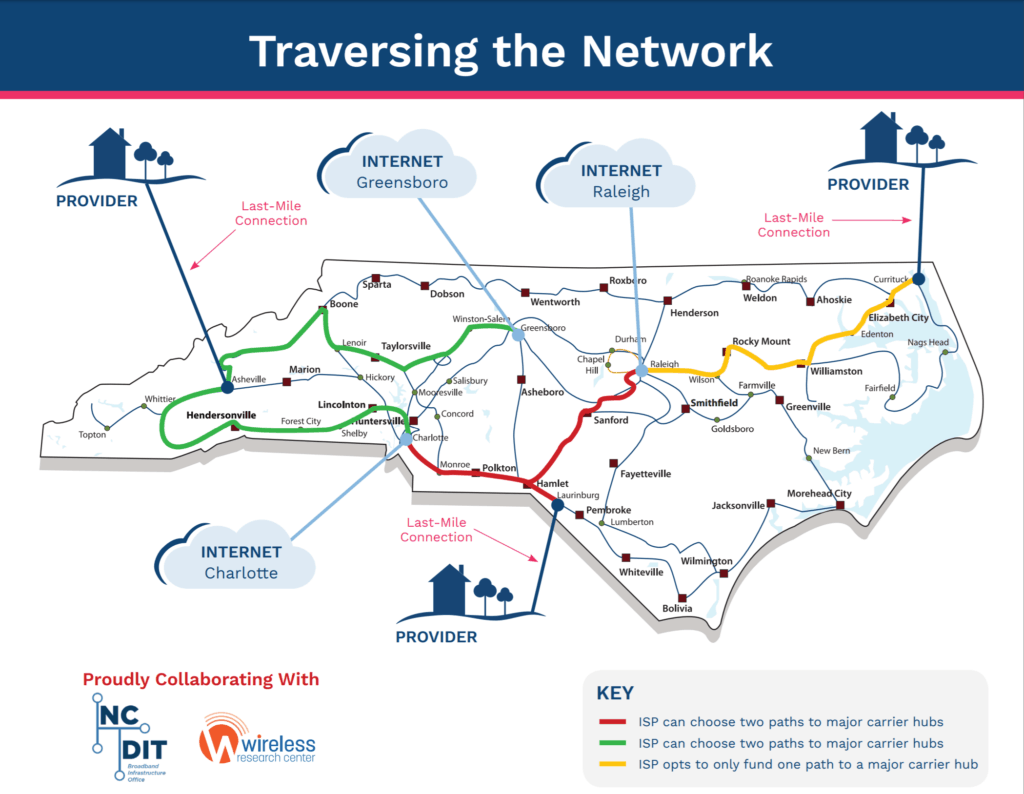

As a middle mile backbone provider to anchor institutions, MCNC does not provide last mile fiber that households and small businesses need. Private providers, however, can tap into MCNC’s network to do just that.

MCNC’s fiber backbone is an open access network, something that Davis said is unusual. That means all of their fiber can be leased by broadband internet service providers, cable operators, wireless carriers, and commercial businesses.

Davis said she would like to see more leveraging of MCNC’s network, and that MCNC’s status as a nonprofit ensures financial transparency and allows them to offer high-quality fiber at a lower cost than commercial companies.

“We have a public price sheet that says here’s the fiber, here’s what you can do, here’s where the handholds are where you can access it, and here’s the public price list,” Davis said.

But the solution is not so simple. According to Davis, many for-profit companies are hesitant to lease MCNC’s fiber because they prefer to own and operate everything within their network.

The good news is that many smaller companies are leasing from MCNC, including telephone co-ops, electric co-ops, and other smaller telecommunications companies.

“You are seeing these kind of pockets of leadership that are saying, ‘I’m gonna find a way to get people connected in my rural region,'” Davis said.

And she sees those telephone co-ops and electric co-ops as the organizations that will lead the way in ensuring rural residential broadband internet access.

“It’s not a big jump to go from providing electric service to providing broadband service. So we do think that they are going to be the leaders in this,” Davis said.

Leveraging a fiber network like MCNC’s doesn’t necessarily mean building last mile fiber to every home.

During a recent virtual town hall, Patrick Woodie, president of the NC Rural Center, said that building last mile fiber to every home or business in the state wouldn’t be possible or affordable. Instead, Woodie said, we “have to be agnostic about the technology,” and consider a mix of solutions including high-speed fixed wireless internet.

For example, Davis said a company could lease MCNC’s fiber, hang wireless technology off of a grain silo or building in rural area, and beam out connectivity from there.

Beyond ensuring access, Davis said the issue of affordability must be considered. Even if last mile fiber is built out to residential areas, the people living there have to be able to afford it.

One idea Davis offered up for addressing this issue is offering vouchers to cover the cost of home internet connectivity for public school students living in Tier 1 counties or who are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, similar to how the federal Lifeline program subsidizes telephone or broadband internet services for low-income households.

“It is a complex problem. It’s not just about the supply. It’s about the demand and the profit of the demand,” she said.

GREAT grants

In 2018, the General Assembly authorized (S.L. 2018-5) the Growing Rural Economies with Access to Technology (GREAT) Grants, a program offered through the state’s Broadband Infrastructure Office, housed in the Department of Information Technology. The program was later amended in 2019 (S.L. 2019-230).

Under the program, private providers of broadband services can apply for grant funding to “facilitate the deployment of broadband service to unserved areas” in Tier 1 counties. The funds are to help “anybody who is trying to make this business model work in a rural area,” Davis said. Applications for the latest round of funding closed in March, but you can find more details on the application process, guidelines, and FAQs here.

The $15 million available annually through the GREAT program helps to subsidize the costs of the companies providing connectivity in rural areas. In 2019, the grant program gave $9.9 million to broadband internet providers, and grant recipients provided an additional $6.8 million in matching funds. That money will be used to serve 467 businesses and 9,035 households. For a map of where the funds are being used, click here.

Innovating at the local level

In 2011, House Bill 129, the “Level Playing Field/Local Gov’t Competition” act, became law without the governor’s signature after then-Gov. Bev Perdue decided not to sign or veto it. The bill states its purpose as protecting “jobs and investment by regulating local government competition with private business.” In essence, it places restrictions on the ability of municipalities to establish their own broadband networks. Opponents said the law was an industry-backed proposal to prevent further competition from entering the market.

Davis said it’s important to be careful when it comes to spending taxpayer money to establish something as complex and costly as broadband service, but she also thinks that towns and counties have more flexibility under the law than they might assume.

“There are towns and counties that think, ‘Oh, I can’t do anything around fiber and broadband because that’s against the law.’ That is not the truth,” Davis said.

For example, Davis said a town might decide to build its own fiber network to connect its city buildings, parks, and public health clinics. Building a fiber ring for the city’s own use would be within the bounds of the law. Then, with “some understanding and some help, you could put excess fiber in that conduit that you could lease to a telecom partner and then they could go off and provide service,” Davis said.

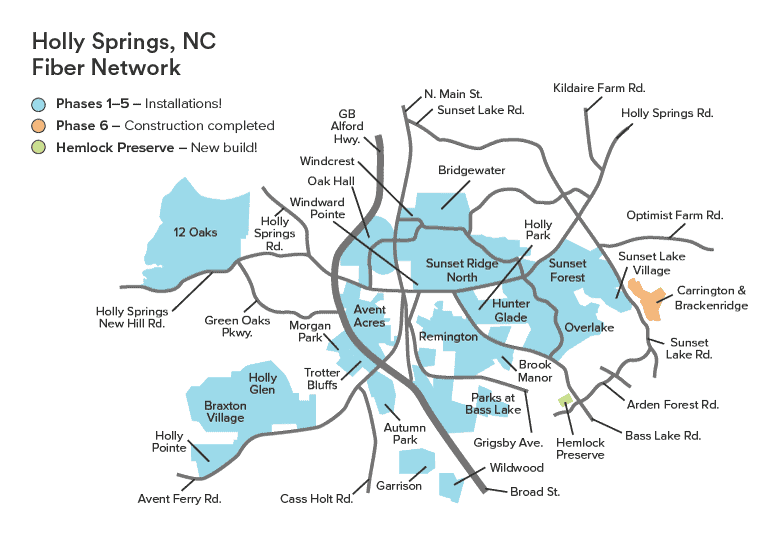

Holly Springs, a town in Wake County, recently took on a similar project. According to Davis, the town hired a company called CTC Technology & Energy (CTC) to assess its connectivity needs. For example, they might have identified the cost savings that would be possible if fiber internet allowed a security guard to patrol the town’s parks from one central location rather than by driving around to each one.

The study determined how long it would take the town to get a return on investment if a ring of fiber was built. Ultimately, the 2013 report recommended that the town proceed with its fiber plans to serve town facilities and “consider an overall strategy that includes certain initiatives to leverage the initial investment to meet the needs of Holly Springs businesses, residents, and service providers.” You can read the entire CTC report here, titled “The Business Case for Government Fiber Optics in Holly Springs.”

The town moved forward with its plan, and when the fiber ring was built, Davis said it was carefully engineered to offer excess fiber. Then, the town opened up a bid to private telecom companies.

“If you want to come to Holly Springs and provide fiber to the home, we will lease to you at a very competitive rate, our top quality fiber ring for you to be able to access,” Davis said, explaining the process. Ting, a Canadian-based company, is now using the town’s fiber ring to build out last mile fiber connections to homes.

According to the town’s website, the entire project cost about $1.5 million, paid for through a 10-year loan approved by the town council that is being paid back using the funds currently spent on facility interconnection services. “Because the amounts are roughly equivalent, the result after 10 years will be a Town-owned fiber network, an asset with a lifespan of 30 years or more,” reads the website.

Davis acknowledges this kind of solution would require subsidies, grants, and fundraising in more rural areas or in areas with a lower tax base, but said these kinds of partnerships are allowable under current law.

“It’s going to take everybody – local money, state money, federal money, easing of regulations around the telephone co-ops and electrical co-ops – to allow them to do more,” Davis said. “It’s going to take everybody coming together to find a solution to this, because it’s hard work. If it was easy, or anybody could make money, it would have been done.”

Recommended reading