For the fourth fall, North Carolina’s kindergarten teachers are collecting developmental information for an assessment the state hopes will help shed light on the experiences of students during crucial early years of transition and learning. Some teachers are not seeing the benefit to a process meant to improve their instruction and relationships with students.

The Kindergarten Entry Assessment (KEA) requires teachers to collect pieces of observation-based evidence on different skills and areas of development in the first 60 days of kindergarten. Katelin Row, principal of Coker-Wimberly Elementary School in Edgecombe County, said she sees the importance of paying attention to aspects of students’ physical, emotional, and social development outside of reading and math scores. This is one aim of the assessment: that if teachers have to record information on students’ nonacademic progress, they will notice strengths and weaknesses they wouldn’t otherwise. They will get to know their students better and be able to better meet their needs.

“It’s not that it’s not helpful or important information, because it certainly is,” Row said. “Knowing the developmental level of your kids and all of those domains that go along with it, are so critical to being able to develop a whole child and to really support kids and build a strong foundation for academic learning after those are developed. But teachers are already doing that as best practice.”

Row kept coming up with the same word to describe how the KEA fits into the rest of the responsibilities a kindergarten teacher has: disconnected. There is no connection between KEA results and other data, like literacy assessments, that teachers are already collecting, analyzing, and reporting to the state. Though the measure is meant to be formative, meaning a tool to guide instruction, Row said it is not clear what teachers should do with the information they are collecting. And after teachers submit the information in November, there is no connection between the KEA and the student going forward.

“It just causes things to be a little bit more disconnected when you have all these stipulations on things teachers are already doing but then you’re not seeing any relevance of it after that point.”

What is the KEA?

The KEA was developed in 2013 by a team of teachers, parents, and education scholars convened by former Superintendent of Public Instruction June Atkinson. According to the office’s website, this group, the North Carolina K-3 Assessment Think Tank, worked with thousands of stakeholders — parents, teachers, and experts — to create the assessment. Find the think tank’s report from that work here. Portions of the KEA were first used in schools in the 2015-16 school year.

Deputy State Superintendent for Innovation Eric Hall said the assessment originally came from language in a federal piece of legislation, the Excellent Public Schools Act. The initiative’s initial funding came from the federal Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge Grant. State legislation, passed in 2012 and amended in 2015, lists goals of the assessment, including finding out where students are upon kindergarten entry, informing teacher instruction, reducing “the achievement gap” when students start school, and bettering the entire early education system.

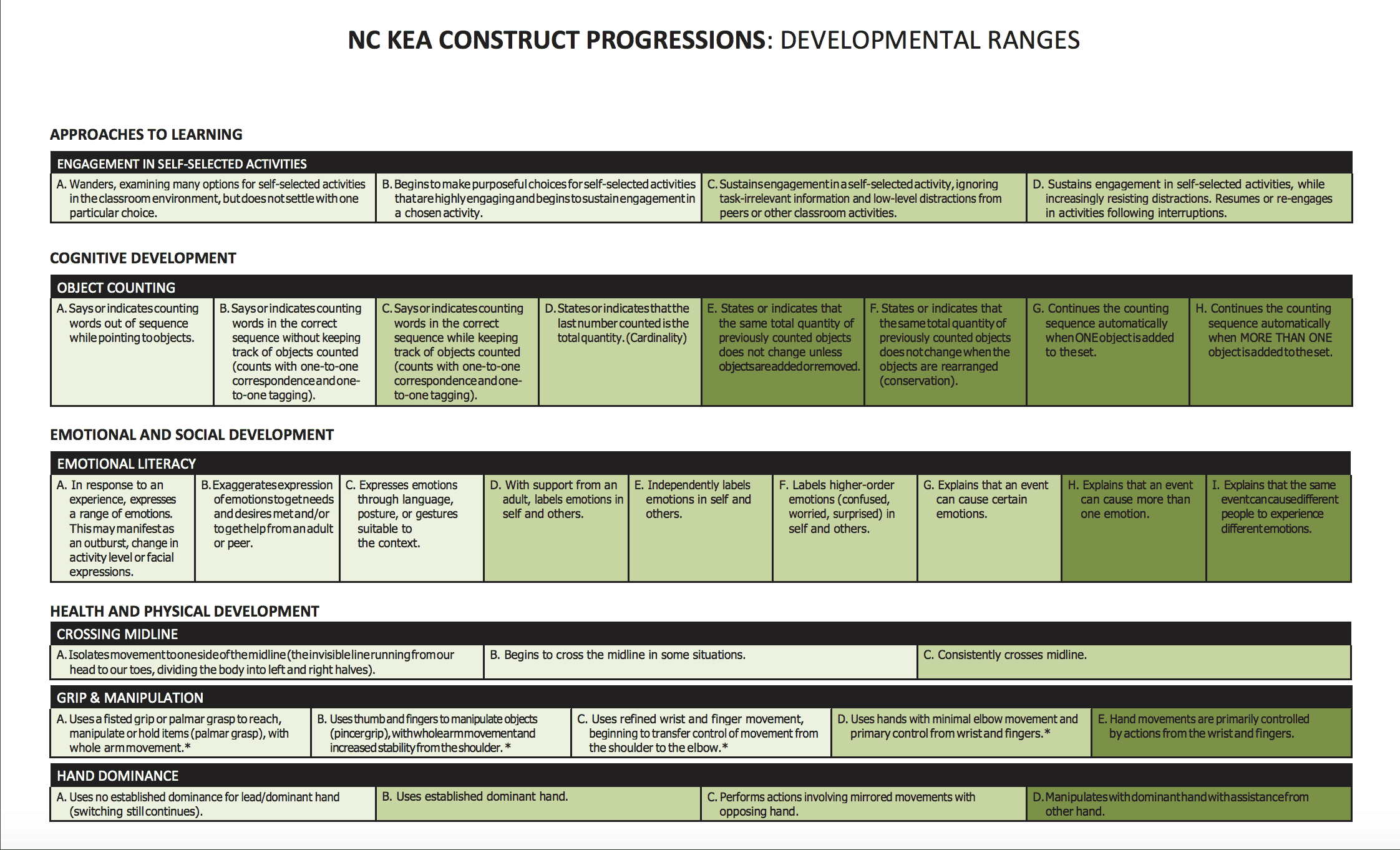

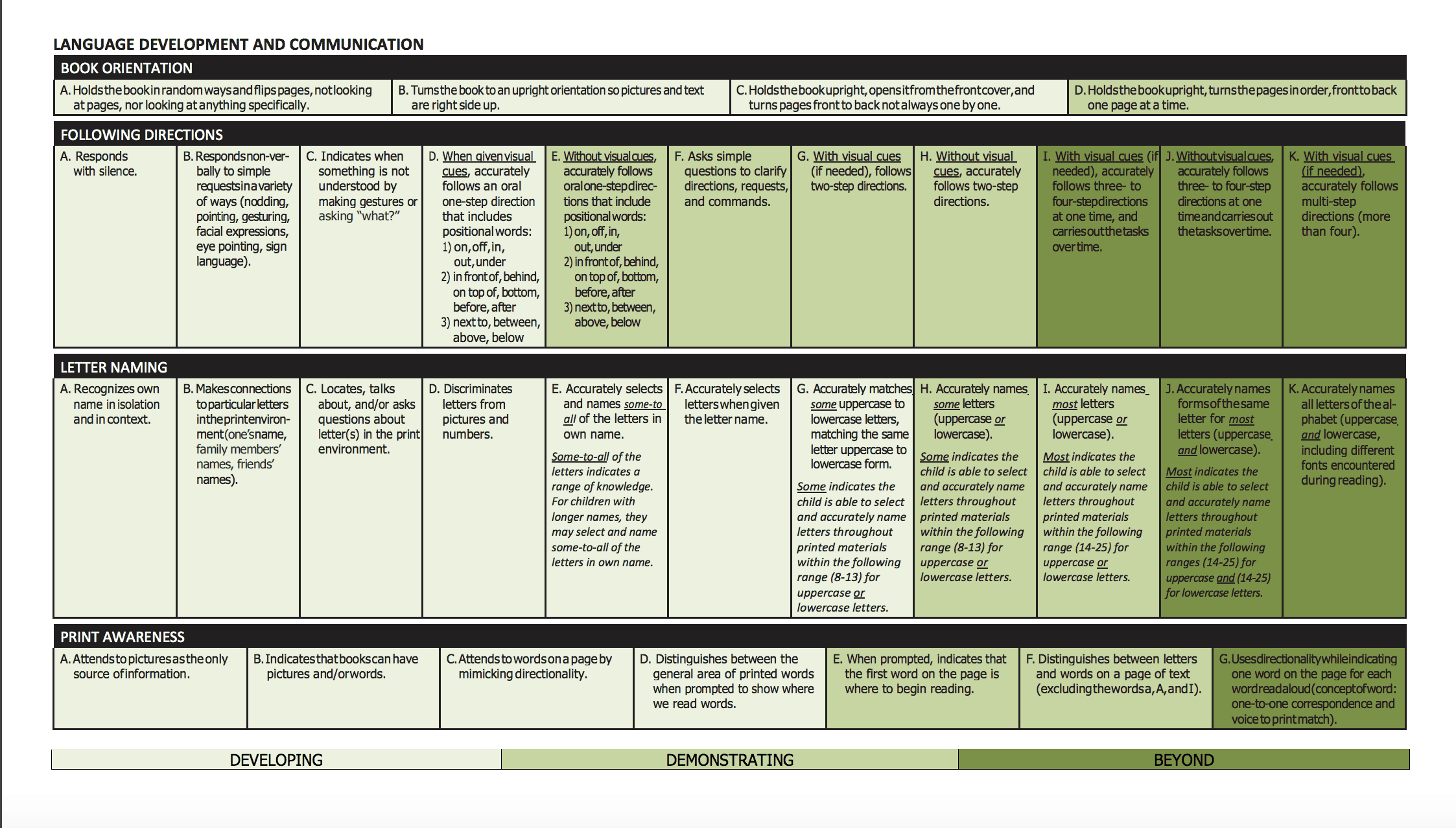

The office’s website describes the assessment’s purpose like so: “The intent is to capture the development of each child at kindergarten entry to inform instruction and education planning. Consistent with expert views on best practice in K-3 assessment, the KEA covers the five domains of child development: approaches to learning, language development and communication, cognitive development, emotional and social development, and health and physical development.”

Each of the five domains has at least one skill, or “construct.” Through the first months of school, teachers are supposed to collect pieces of evidence for each skill and rank each student’s status.

For example, under the “language development and communication” domain, there are three constructs to look for in students: book orientation and print awareness, following directions, and letter naming. Each of those constructs are broken down into more specific descriptions of what children should be able to do. Under letter naming, there are a handful of those detailed skills, like “locates, talks about, and/or asks questions about letter(s) in the print environment,” and “discriminates letters from pictures and numbers.”

Teachers are supposed to look at evidence as the school year progresses and make preliminary placements of where students are, like a rating. Those are meant to be used to make changes in instruction based on the children’s status in different areas. Final placements for each construct are made at the end of the 60 days.

Richard Lambert, a UNC-Charlotte professor of educational leadership, has worked with the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) to study the KEA’s implementation in specific school districts. Lambert said levels of implementation and teacher opinions have varied widely.

In districts where Lambert has seen the implementation go well, like Dare County, he said there are some strategies that have made a difference. Firstly, having district and school implementation teams that are there to answer questions from teachers and help explain the purpose of the assessment is critical. Second, implementation takes time. Dare County, Lambert said, was one of the schools to pilot the KEA and have been able to develop a culture around its importance. Lastly, utilizing the state’s regional consultants can lead to clearer communication from the state to the school.

“It makes a big difference when you have someone communicating the intentions of the initiative directly from the state,” Lambert said. “If you know, in another district, they send someone to a meeting and they hear about it, and then they come back and they say, ‘Well, we’ve got this new mandate, we’ve got to do this thing.’ That’s very different from really understanding why and how.”

In other places, Lambert said he found teachers not collecting enough evidence and, therefore, not being able to make valid placements on the domains of development. Even when teachers were filling out the assessment correctly and understanding its purpose, Lambert said having the results impact instruction is another story.

“Now as far as the question of is the data really being used to affect individualized instruction and so forth, that’s probably the biggest challenge in the early childhood field,” he said.

Many states use similar tools that, like North Carolina’s, are informed by a “whole child” approach — less focused on test scores and more about the overall development of children.

Some researchers have asked the same question as Lambert: does it make a difference in instruction and student learning? A 2016 national report from the U.S. Department of Education found kindergarten entry assessments had no statistically significant impact on children’s performance in math or reading in the spring assessments taken after teachers used KEAs in the fall.

Gwenevere Peebles, a multi-classroom reading teacher at Coker-Wimberly Elementary, feels the assessment is spot-on in its focus. Peebles, who works with multiple early grade teachers in the school, recognized that she has a different perspective than classroom teachers who have to record the information.

“My thing is I think it’s really important because we can not get the academic piece if we don’t have those social or emotional pieces,” she said.

Peebles said the helpfulness of the assessment depends on the teacher and can be undermined by the focus on academic testing.

“It probably doesn’t get the attention it should get,” she said.

Assessing rather than teaching

Too much testing has long been a concern of teachers, parents, and students. The KEA, for some, is an additional burden in an environment that puts importance on other types of tests.

Bailey Elementary kindergarten teachers said they already have to keep student portfolios for their school district. Due to technological issues, they said they were not able to access the online application that allows teachers to input text, photos, and videos for the KEA at the beginning of the year. That meant teachers were doing their best to keep track of information by hand. They also were skeptical that the pieces of evidence were paid attention to, even by the state, after they hit ‘submit’ in November.

“Honestly, we do it because we’re told we have to, but once we do it, we’re done,” said Glynnis Williams, one of those kindergarten teachers. “… We feel like we spend more time assessing than we do teaching.”

With pressure around literacy up to the first End of Grade test in third grade, some teachers are feeling they must focus on tracking academics in kindergarten instead of the basic foundational skills the KEA focuses on.

“You have to evaluate do they know their academic skills not their fine motor,” said Dale Murray, another Bailey Elementary teacher.

Murray said she does have one student this year whose fine motor skills are not where they should be. In that case, she said the test can point out students who need additional testing to determine if the child has special needs.

Annette Kent, a Coker-Wimberly kindergarten teacher, agrees that the assessment is more relevant for students at lower developmental and academic levels.

“It makes me more aware of where some of my lower kids are, especially those that are not holding their pencil correctly and some of those types of skills that they should have coming into kindergarten,” Kent said. “So it makes me more aware, and when I see them not holding that pencil, it makes me want to go ahead and say, ‘I want to do this because I need to do it for the KEA,’ but still, I’m working with that child on that level. So it does bring some things to light. But when it comes to those children that already [have] those skills, O.K. what do I do with them?”

McNab, who teaches kindergarten math at Coker-Wimberly, said she knows social and emotional development is important, but academics normally prevail in priority. Correcting pencil hold or crossing midline, she said, are skills she would automatically correct in students.

“I feel like it’s just kind of work,” she said.

Hall said the state department hears the over-testing concern often. Hall, who is new to his position, said he plans to have conversations in the coming months with the State Board of Education and other department officials on how to best address that concern.

“Where do we also look at some opportunities to reduce testing over time?” Hall said. “And how does all this come together into a real comprehensive strategic strategy around good authentic assessment that tells us what we need to do to support students while not having an environment that is so test-heavy that we’re not creating the opportunities to really go back and develop some of those additional skills?”

He said data is important in gauging if students are understanding content, as well as seeing broader trends over time across the state.

Hall continued, “Where are there some opportunities to re-envision some of the assessment practices that we have while making sure that we stay connected to what is really the prime functions of assessment, and that is about how we’re monitoring to see if students are really mastering the information and the content and developing the proficiency, and then how are we using those as tools to really monitor growth over time?”

What assessments are prioritized instead?

From the start of kindergarten through the end of second grade, teachers monitor students’ reading and grammar skills through a program called mClass. The results of these assessments, given three times a year, are tracked to monitor student growth both in the classroom and by the state.

The EVAAS tool, which is factored into the state’s accountability model and measures academic growth of subsets of children over time, also uses mClass assessment results. Teachers are reviewed based on student performance on mClass assessments as well.

Though the assessment is focused on academic skills, it is meant to be formative like the KEA. Often, teachers in early grades will use how students score on the assessments to create small groups. When teaching students how to read, this helps teachers focus on one group, and one reading level, at a time.

McNab said mClass, which she used to use with second graders, is helpful in that it creates immediate activities for students depending on where they are and gives recommendations to teachers on how to improve student performance.

At Coker-Wimberly, students also use iReady, which is an online assessment that gauges where students are in math and reading and gives them independent activities depending on their knowledge and skills. This is used in other schools across the state but is implemented on a school-by-school basis instead of being required by the state. Some teachers find it useful for supplementary work to fill in learning gaps in students who are behind grade level.

There is also the K-2 math assessment, which McNab said takes a couple weeks to administer to her entire class. The teacher has to read off certain problems and see if students can perform tasks like recognizing teen numbers and “subitizing,” or counting objects mentally. The assessment is created by the state department but, according to DPI’s website, can be modified based on local districts’ needs.

And this year, Kent said a program new to Coker-Wimberly called Benchmark Literacy has been useful in teaching reading, grammar, and writing. The program has units that last five to six weeks, and children are tested before and after each unit to measure if they are proficient in a specific standard. This is a district-wide initiative in Edgecombe County, Kent said.

“(The KEA) is a good program, but we already have so many programs going on,” Kent said.

A piece of a bigger picture

Lambert, in addition to looking at KEA implementation, has been working with DPI to find how best to track and utilize KEA results statewide.

That means developing some kind of number to associate with the status teachers give to students in the five domains, while keeping the assessment results detached from teacher or school accountability.

“We’ve been helping guide them through a process of saying, ‘What is the best way to convert those (KEA results) into something that is more appropriate to record?’”

This week the State Board will look at the possibility of “developmental ranges” as part of the KEA, which Hall said will be useful in starting to make sense of results at the state level that have so far just been for teacher use in the classroom. The ranges, “developing,” “demonstrating,” and “beyond,” were developed by a KEA Interpretation Panel in meetings in January and February 2017 and in February 2018. A report of their recommendations on how to meaningfully interpret KEA data will be presented this week at the State Board meeting.

“How do we start to build the capacity to collect that kind of information back from the LEAs and start really understanding what are we gleaming from that data?” Hall said.

Hall said he is excited about the chance to get a more complete view of where kindergartners are across the state upon entry into the education system.

“The KEA, up until now, has not been a tool that we’ve been collecting that kind of data on at the state level,” Hall said. “And so I think this is going to help tell us more about what’s the full picture and the full story of what’s happening from kindergarten … really all the way up to third grade.”

According to the report, the developmental ranges are to help both the state and educators in understanding KEA results:

“The OEL (Office of Early Learning) will consider the Panel’s recommendations and develop a framework for categories used when reporting aggregate data from children’s KEA assessments. In addition, the framework will be used to help communicate aggregate KEA data to teachers, administrators, families and the early childhood community. Finally, the framework may be useful to support teachers’ efforts to interpret data and plan instruction that is appropriate for entering kindergartners. The ranges and resulting categories of data are not intended for use in performance evaluation of early education programs, or educators, or for high stakes decisions. Instead, they will serve as guides that can support greater understanding of the status of North Carolina’s kindergarteners in the aggregate, and help teachers in deriving meaning from the KEA results of children they are teaching.”

Lambert said the assessment could be the first step in developing a set of information that follows students starting before kindergarten and well into their elementary years. A portfolio like this, which he says other states are beginning to develop, would provide a chance for pre-K and kindergarten teachers to share important information about students as they switch systems. He said he has seen a lack of communication between pre-K and kindergarten teachers, even those in the same building, and even when pre-K teachers already have in-depth data and information on the child.

“It’s just the classic thing in education where the right hand isn’t doing what the left hand is doing,” Lambert said.

The assessments used in N.C. Pre-K, the state’s preschool program for at-risk four-year-olds, uses an assessment focused around development. Kent, who used to teach pre-K before switching to kindergarten, said the observation-based assessment seems to work better in the pre-K setting.

For one, students’ days are centered around play-based learning, often in stations around the classroom, which provides a chance for teachers to watch. Kent said she felt the entire purpose of the pre-K setting was overall development. Without stress on academics, the assessment made more sense. And finally, Kent said the pre-K assessment had 50 different standards and encompassed more skills.

“As far as the standards go, it’s not that much in-depth,” Kent said about the KEA compared to what she experienced in pre-K. “… It’s only about nine, 10, or whatever. To me, that’s not the whole child.”

Lambert said he hopes the state will think long-term and expand the assessment to be meaningful across grades.

“I hope the state continues to fund this initiative so that, in the end, we have a seamless process of assessment across all their early years so teachers are really receiving a rich set of data from the previous year’s teacher,” he said. “The theory is then you would continue to be able to individualize instruction … That’s the big picture, and whether we end up getting there or not, I don’t know.”