The youngest student at Appalachian State University last year was 5 years old.

She’s not a prodigy — at least, not as far as anyone knows so far. She’s not even working on her bachelor’s degree. She’s a kindergartner who became a Mountaineer by way of her lab school: Appalachian State University Academy at Middle Fork.

Last year, a two-year old law took effect that put five underperforming schools in underperforming districts under the leadership of “constituent” UNC System schools of education. The idea is that using university research to discover innovative ways to raise up struggling communities and students could turn around failing schools.

Middle Fork Elementary School was a natural choice as one of these five laboratory schools — it had been an “F” graded school the past four years. It was only natural that App State be chosen as a constituent University — it was founded 120 years ago as a teacher’s college. What may have been a little unnatural was pairing the two together.

App State is in Boone, a solid two-hour drive down Route 421 from App Academy in Walkertown, a Forsyth County town of 5,000 people just a few miles Northeast of Winston Salem. The separation in miles happens also to match a demographic distance, too. Watauga County is 92% white, where the average home is worth about $250,000. Forsyth County is 56% white, with an average home value about $100,000 lower than in the Boone area.

Despite the distance, though, one visit to App Academy and it is immediately apparent that the ties that bind the institutions are knotted tightly. And the hands tying them together belong to leaders at the very top.

“These kids are all Appalachian State University students now,” App State Chancellor Sheri Everts told her staff after the partnership was announced. “And we’re going to do everything we can to support them.”

Boot prints are tracked along the primary academy’s floors to show young students where to stand and stop in the halls. Outside of classroom doors, “Progress Mountain” boards are fastened to motivate students to work together as a class toward academic and behavioral achievement. App State pennants, logos, and photos decorate the hallways. The message is clear, even before you get a load of the research-based curriculum designed by App State’s Reich College of Education faculty: This is now App State country.

“We wanted to bring a little bit of the mountains down to Winston-Salem,” App State creative director Troy Tuttle said.

They succeeded. And after Year One as a lab school, App Academy Principal Tasha Hall-Powell calls the partnership a success, too

“We have children who come to school more often — our attendance rate has improved and our staff attendance rate has improved,” Hall-Powell said. “People want to be here. They work hard, they stay late, they come early. Our children are more engaged with reading and writing. It’s a special place.”

The to-do list for someone starting an elementary school is unimaginably long. The breadth of needed expertise — facility management, data tracking and reporting, student safety, nutrition, discipline, these are only some of the issues leaders confront. And that’s before you consider academic ones, like curriculum and assessment.

It’s not surprising some critics of lab schools point to bumpy starts by UNC System constituent schools, which are inexperienced with primary public education management, to support their argument that the lab school pilot won’t work. But App State and App Academy seem to stand in opposition to any such argument.

From administration to academics, and particularly with respect to discipline and safety, the launch was smooth.

Leaders began with a first-things-first attitude, identifying their priorities as learning together, developing and distributing a core curriculum, and adopting a whole child approach. They needed priorities because they recognized not everything they envisioned would get done in the first year.

“We couldn’t do everything in the beginning,” said Amie Snow, Director of Curriculum and Instruction at the Academy. “There were so many things that we had to learn beyond the curriculum — how to open a school together, what are our procedures, what are our expectations — and then learning how to work with the university and figure out how our roles combined to make all this come together.”

While the university worked on a curriculum, the school wanted to focus on the culture. As a historically-underperforming school, the administrators and teachers knew well that they had a lot of kids that didn’t believe they could achieve at high levels. They also admitted that behavioral issues had been a problem at the school, a byproduct of disconnect between the kids and the learning.

So the Academy began work on what would become the Academy’s Mountaineer pledge:

I’m a Mountaineer. Do you know what that means?

I show Honesty, Integrity, Kindness, and Excellence in all that I do. You can, too.

I’m a Mountaineer. You’re a Mountaineer. We are Mountaineers.

Ready, set, HIKE.

They came up with Progress Mountain, where class-wide accomplishments and positivity are recognized by advancing a classroom’s “hiker” forward along prongs in a wooden mountain board. When a classroom reaches the other end of the mountain, they are rewarded with pizza parties and other celebrations. The Academy also has boys and girls mentoring groups, called Mountaineer Scholars and Her Way, respectively, where participating fifth graders are mentored by teachers outside of class.

They came up with Progress Mountain, where class-wide accomplishments and positivity are recognized by advancing a classroom’s “hiker” forward along prongs in a wooden mountain board. When a classroom reaches the other end of the mountain, they are rewarded with pizza parties and other celebrations. The Academy also has boys and girls mentoring groups, called Mountaineer Scholars and Her Way, respectively, where participating fifth graders are mentored by teachers outside of class.

“It’s the relationships,” Hall-Powell said. “I think when kids see that the adults are invested in them, and that they really mean what they say to them and they engage with them — they greet them, hug them, they just pour into them — it’s genuine. And kids are very intuitive. They know when someone has their best interests at heart and they have a passion for them. And I think that’s what is living in this building.”

The next priority? Designing a curriculum.

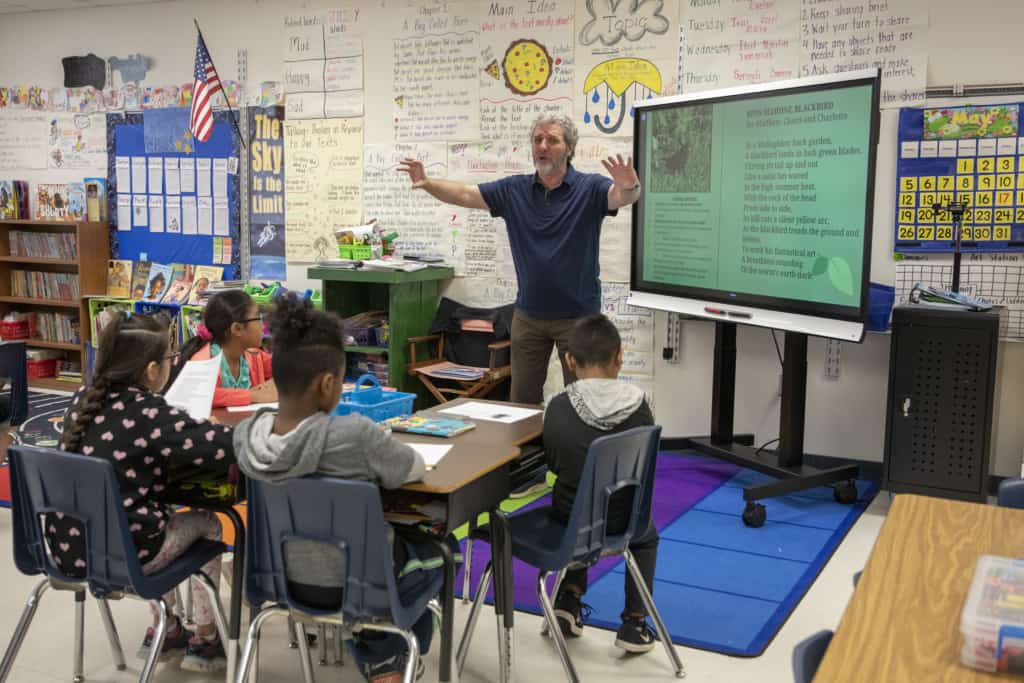

Work on the curriculum began more a than year before students showed up in classrooms, before the App State and App Academy teams would meet — indeed, even before the App Academy hires were finalized.

App State sent feelers out to their college of education faculty to identify the curriculum design team. The university’s college of education has history dating back 12 decades of preparing North Carolina’s future teachers. With that spirit, a foundation in research-based teaching, and an emphasis on ensuring students could relate to lessons, they set out to design a curriculum that would meet the needs of a school that had shown low proficiency for years.

A couple months before the Academy would open its doors to students, teachers were sitting with curriculum designers and university mentors to receive professional development and training.

Monique Johnson started at Middle Fork four years ago. She watched the atmosphere and priorities transform before her eyes as students came into the classroom and teachers implemented the new curriculum.

“As a teacher, I’m teaching on a whole other level than I came in teaching on because it’s allowed me to embrace new things and different approaches,” fifth-grade teacher Monique Johnson said. “How to meet students where they are, how to figure out where they are.”

Johnson considers what it feels like now compared to what it was before and she takes a deep and purposeful breath before speaking.

“It was quite overwhelming when I first started,” she said. “Everything was Common Core. So everything was taught through strict curriculum, which did not allow any flexibility for us to add any of our own reading resources, writing resources, poetry. So there was a lot of things that we were limited on. And we were kind of teaching to the test, so it was very difficult and hard to get the students to retain all of the information that we were providing in such limited time.”

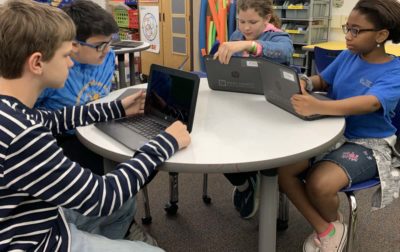

At a lab school, the focus is on innovation and finding strategies that best reach students and help them grow and achieve. Trying these research-based strategies, App State’s faculty thought, would work best on a smaller scale. Last year, for example, Johnson had 28 students in her class. This year, she has 18.

“We had larger groups of fifth graders last year that were struggling readers, struggling writers, struggling in math — struggling in all areas,” Johnson said. “Especially with their behavior and attitude towards the learning. And so because it was so strict, there was no flexibility for the students to enjoy learning, or we couldn’t be creative as far as science projects.”

Now, they can be creative throughout the curriculum. In fact, that’s the main goal. Whereas much of their time was spent teaching the standard course of study or addressing behavioral issues, now the focus is on making sure that students connect to what is being taught.

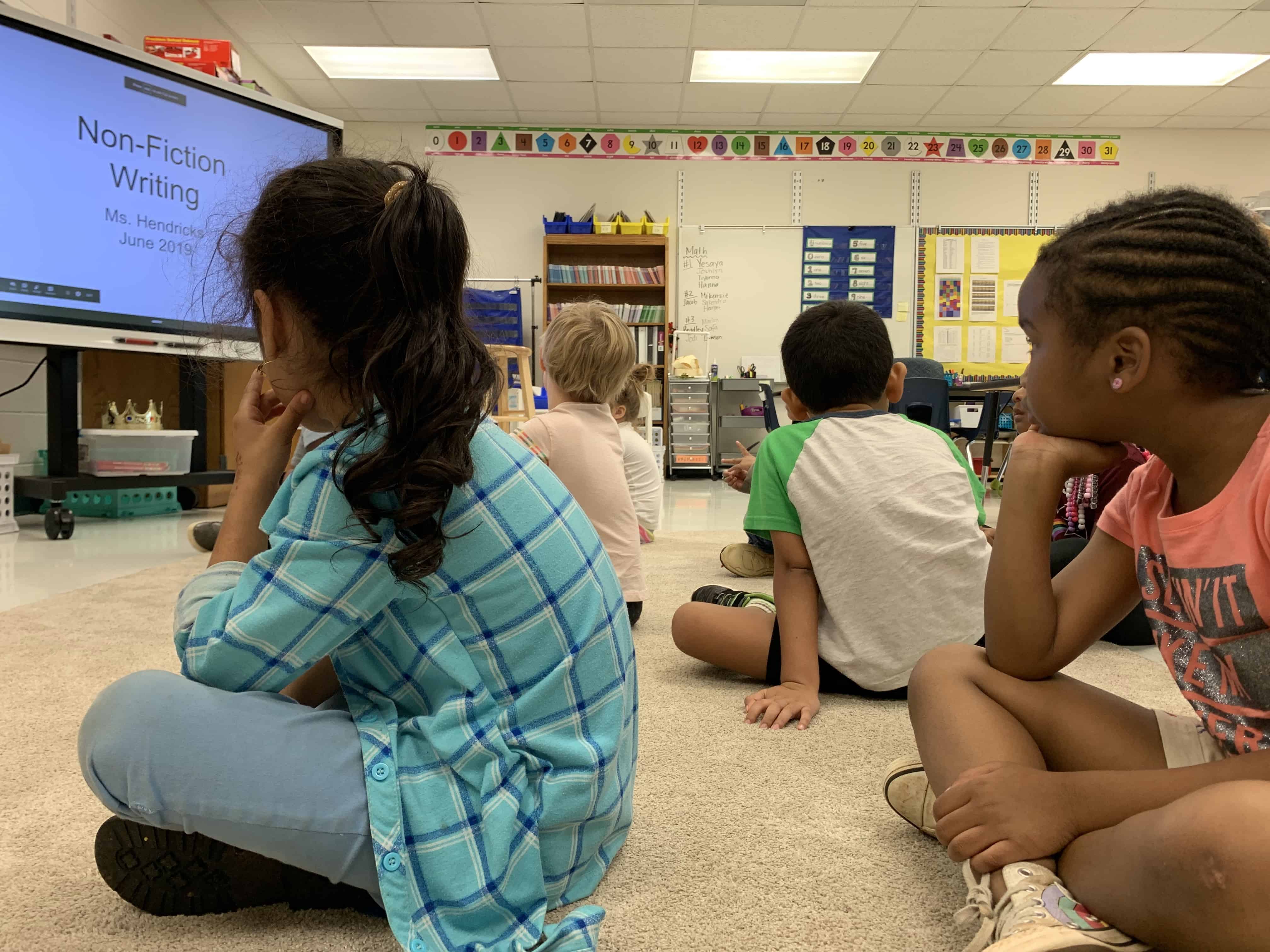

In designing the curriculum, ASU faculty focus on ensuring it is inclusive, integrated, and designed to improve literacy throughout the grade levels. App State faculty Beth Frye, Lisa Poling, Eric Gross, Lisa Gross, Aftynne Cheek, and Rebecca Jordan designed the curriculum with Snow and focused on customizing the experience for a population where 83% of students are either African-American or Hispanic.

“They have really impacted and provided structure for us,” Johnson said. “… Having those instructors to come down to support us, and to give us out-of-the-box ideas, was all very helpful for all of the teaching staff. Not just myself, but for all of us.”

The new curriculum includes customizing lessons for each student, redesigned reading lists that have inclusive and diverse characters and story lines, more hands-on activities for the students, and fewer lectures from the teachers.

“I feel like this year, we have them involved too, and everything’s exciting,” first-grade teacher Alicia Kinzer said. “It’s not just lecture. We have the smart boards. We have sorts. We have them building things. They’re not just looking at me doing things. They’re doing things.”

What’s more, the ASU faculty brought resources. Instead of teachers having to independently go online or searching for supporting materials, everything has been brought in-house into subject rooms where teachers can quickly find classroom materials.

“Sometimes I’m still like, ‘Gosh, I’ve got to find a book for this,’” Kinzer said, “and they’ll say, ‘Hey, Ms. Kinzer, we’ve got books for you right here.’ I thought I was going to have to go out and find everything myself, but it’s not. Everything’s given to you here.”

That may seem like a small adjustment, but it’s the kind of little efficiency that creates just enough room in the teachers’ days to brainstorm more engaging ways to present the lesson and progress through the day. Now Johnson’s class begins with a game in the morning to help students ease into the day.

“It’s not just sit down, be quiet, don’t touch anything,” Johnson said. “We’re actually doing some STEM activity or playing chess.”

One of the most successful changes has been to the reading list, which features many more novels with which the students feel connected. In the story Fish in a Tree, a young girl who struggles with reading uses distractions and disruptions to hide her belief that she’s dumb. But with the help of a caring teacher and her classmates, she surpasses her own expectations. At a school where many of the students were not reading at grade level, the story hit home.

The reading list also has more books with main characters that are black and brown, and teachers watched as students expressed surprise that the boy or girl on the cover looked just like them.

“And that really has to do with App State and Dr. Snow, asking, ‘What high-interest, engaging material can we bring into this school for characters that experience things similar to what they experience or look like they look?’ They can identify and relate to some of what the characters are going through.”

The curriculum is also open to change and growth. Johnson and Kinzer say that Snow and the App State team have made it clear that reaching each student is paramount, and because the teachers are on the front lines, the teachers’ ideas are equally important.

“At this point, I can bring my own creativity,” Johnson said. “So once the curriculum is presented to me, then I’m thinking, ‘How can I take this deeper? How can I make sure I connect with this student?’”

For Johnson, as she saw the students connect with characters in the novels and open up more about their own lives, she realized it was important to encourage them to continue to open up, be confident, and take pride in themselves.

“I wanted them to be able to say — I AM a learner. I AM an author. I AM great,” Johnson said.

So she introduced “I AM” journals in her classroom, where the students could do free writing and share “what is on their minds or heart or things that are happening at home.” She floated the idea by Snow, expressing her belief that most of her students struggled with confidence and could benefit from an outlet like this.

Snow was on board right away.

“The teachers have done an incredible job,” Snow said. “And I think what they love about it is that, yes, we do provide the curriculum, we do have structure. But within the structure, we also have flexibility for you to talk to us about what your students need, to make informed decisions about what they need — because they are experts. They’ve been there with their children all day long. They know them better than any of us do. So when they come to us and say, ‘Hey, this is working’ or ‘Well, can we try this?’ We’re like, absolutely. Let’s see how it goes. And I think that makes them feel empowered and feel trusted and confident in who they are.”

The relief and joy is evident in first-grade teacher Alicia Kinzer’s eyes. “It’s been my best year, ever,” said Kinzer, who will now be a fourth-year teacher.

The law provides for establishing lab schools in underperforming districts. These districts tend to have things in common: fewer resources, high numbers of free or reduced lunch kids, low regional income, and low levels of adult college graduates.

The community housing the Academy is recognized by the USDA as a Community Eligibility Provision district, which is an agency guideline that provides the nation’s highest poverty schools to serve breakfast and lunch at no cost to all enrolled students. At the Academy, more than 90% of the students would have qualified anyway.

The experience for teachers in underperforming schools serving at-risk populations is much different from those in high-performing ones. The job description, Johnson and Kinzer say, often means much more than teaching. It’s monitoring behaviors, addressing discipline issues, and being mindful of hunger or other health concerns. On top of that, many of the children are not reading at grade level and are struggling in math, science, and social studies.

“With Middle Fork, we’ve had high transitions and turnover rates with teachers who are experiencing, I won’t say burnout, but just the difficulty in maintaining what’s needed for a high-risk population,” Hall-Powell said. “The work is really hard, [especially] when you add the emotional component.”

Now, the smaller class sizes and focus on everyday engagement (as opposed to standardized test scores) has made the experience of being at school fun and exciting again, say both students and teachers at the Academy.

“I am excited that we are not teaching to the test and that doesn’t put that weight on my shoulders,” Johnson said. “I’m able to be more free to really teach them exactly what they need. Exactly what they need.”

Next year, 42 of the school’s 45 teachers will return, a marked difference from the high turnover rates from before the school became a lab school. The teachers are working as hard, they say, and sometimes — given the personalized approach and custom curriculum — they may be working harder. But the payoff is so great, and the days are so fulfilling, they say, the quality of life has improved immensely.

Boyd has taught for 31 years in public schools and when she’s asked why she is still teaching, her response is pointed: “Because we finally got it right.” The banner in her classroom echoes the sentiments of the teachers and students you meet in the hall. It reads: “This is your happy place.”

The discipline issues have largely been a non-issue at the Academy. Hall-Powell says it’s part and parcel with the new way of doing things — the engagement, the personalized attention, everything in the halls that screams App State cares, and everything in the classrooms that shout the teachers do, too.

“A couple years ago, I dreaded pulling into the parking lot,” Kinzer said “Now, I get up, I come in, I cut the lights on, put the chairs down — I’m ready to go. And with the students, they’re excited. They’re asking me, ‘Is it math time yet?’ ‘Is it science time?’ ‘Are we doing an experiment today?’

“Last year, I was counting down the days. For Thanksgiving break and Christmas break and snow days — I would be like, please let it snow. This year, we have school and it’s not stressful. I’m not wondering is such-and-such coming to school today? We don’t have any behavior problems. This year, it’s just been such a joy. This is my third year of teaching and it’s my first year hearing ‘Ms. Kinzer, I love you.’”

The excitement and spirit at App Academy is palpable. And they believe it can be replicated across the state’s public school system — in larger class sizes, even, if it must.

“I feel like there are ways that we can take what we do,” Snow said, “and it could happen in other places.”

She points to the urgency placed on meeting standardized testing measuring sticks in North Carolina public schools. The result is teachers thrown into professional development without any systematic or strategic planning around it. A somewhat chaotic try this, now try this type of approach.

“In a lot of sense, the public school systems want those tests scores to [go up] right away. And if they don’t, they move onto something else rather than taking some time to think about, ‘Is this curriculum working? Let’s trust it. Let’s continue to support our teachers as they move through it with our students and see how we are in three years or four years before we switch it up on them.’

“There are lots of our public schools that are trying their best to put into practice research-based strategies that work for kids. I absolutely believe that. But, at the same time, they’re also expected to do a whole lot of assessment to prove that they’re doing it right. And then their teaching all of a sudden doesn’t feel as genuine and authentic, because in their mind they always have that one thing that they’re being judged by.”

At App Academy, they use research-based curriculum that is relatable to the students. And administrators put no pressure on teachers over End of Grade benchmarks, encouraging them instead to stick with strategies learned from App State mentors. It’s a more logical and reasoned approach, they believe, to fine-tuning their young students’ education.

“If we can all try to get our mindset back on what school should really look like and what our goals really should be for children, for teachers and staff in a school,” Snow says, “we could make changes that could mimic what we’re doing here with our flexibility and the pacing of what we’re teaching. I mean just knowing that they’re not held to a rigid pacing guide, I think that’s a key item because they can take a little more time in an area that a child may have a weakness, but not feel the pressure of somebody who’s going to come in next week and say that I’m not on the mark.”

For instance, instead of focusing on the state-mandated Text Reading and Comprehension inventory (TRC) to measure reading ability, App Academy uses an informal reading inventory, or IRI, which was developed by App State professor, Daryl Morris. This IRI uses word recognition, oral reading passages, silent reading, and spelling to measure pace, accuracy, and comprehension. It takes less time than the hour-long TRC and, unlike the TRC, uses reading rates as a factor in determining a student’s reading level.

Several teachers from App Academy are now studying to get their master’s at App State, where they are learning more about the IRIs, including how to use them effectively (read: diagnostically) and what they can tell them about their students.

“Our IRI is based on over 100 years of reading research,” Snow says, “that tells us that this is the type of assessment that you implement so that you can get the kind of information you need to target introduction for your students. … So our teachers do still do assessments, but we do assessments that give us valid data in a really efficient way.”

Snow and Hall-Powell realize local districts and the state may be apprehensive with so much change — but they hope to show the kind of success at App Academy that makes ignoring the strategies impossible.

“I know we’re going to continue to see growth in other ways, and in ways that the state of North Carolina deems to be the most appropriate way to show success,” Snow said. “I know that’s going to come. I know that we’ll have growth. And I know that over time, our proficiency will continue to grow because of the culture and the curriculum that we’ve put in place here.”

EOG results aren’t in yet, but App Academy staff believe great things are happening already. Their fourth- and fifth-grade Battle of the Books teams won second place in their region — as one of only two low-performing schools to even make the finals. And at winter check-ins, the school saw an 81% increase in average reading test scores.

But it wasn’t the quantifiable evidence that convinced Hall-Powell that the new lab school’s approach is working. Previously, she remembers long periods of times when books in the library didn’t need to be re-shelved. They just stayed on the shelf all the time. Now?

“They’re walking out to cars holding books in their hands,” Hall-Powell said. “I’m worried they’re going to trip over their own feet because their heads are down in books. And they read at lunch. I mean, they just carry books with them all the time.”

Last week, the fifth graders had their graduation ceremony in the gymnasium. App State brought in gold and black balloons that formed the “A” of their logo and as students crossed the stage, they shook hands with College of Education Dean Melba Spooner before Hall-Powell handed them a leather diploma cover embossed in gold foil with “Appalachian State University.” They graduated happy students and motivated learners who feel part of the App State community and now dream about going to college up on the mountain.

That, say those at App Academy, is also measurable success.

“I think success for us is that kids enjoy coming to school and are happy,” Snow said. “And you have people coming in telling us that the vibe they get when they are with us is positive, and that they can tell that the environment supports children and teachers and families. That to me, was a big success for us.”

This is the fourth part in a series on North Carolina’s lab schools. Read an overview of lab schools here, and then read profiles of ECU Community School and D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy.