This is the second article in a series about the Teach for All-Oak Foundation Reaching All Learners Fellowship experience in New Zealand. To learn more about the fellowship, read the first article here.

Aotearoa is the Māori name for New Zealand. It translates to long white cloud, giving New Zealand its nickname as the “Land of the Long White Cloud.” Visitors quickly understand how it got its name as the long, low clouds in the photo above are a common occurrence throughout the country.

The first humans in New Zealand came from Polynesia sometime in the 13th century and settled into different tribes throughout the North and South Islands. They did not start calling themselves Māori until the arrival of European settlers.

The first European to discover New Zealand was the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642. Europeans did not return until the arrival of James Cook in 1769, who circumnavigated and mapped the two islands. British settlers began arriving in the 1800s, and New Zealand became a British colony with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The relationship between the Māori and British cultures has shaped their shared history.

Our week in New Zealand as part of the Teach for All-Oak Foundation Reaching All Learners fellowship was grounded in New Zealand’s history and thus the relationship between the Māori and Pākehā, the Māori term for Europeans. In New Zealand, reaching all learners starts with understanding and embracing students’ unique culture and identity, a result of the country’s shift towards biculturalism over the last 40 years.

The Treaty of Waitangi is considered New Zealand’s founding document. It is an agreement between the British government, under the leadership of Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson, and over 500 Māori chiefs. Significantly, the document was written in English and translated to Māori, producing two documents with important differences. According to the New Zealand government:

“In the English version, Māori cede the sovereignty of New Zealand to Britain; Māori give the Crown an exclusive right to buy lands they wish to sell, and, in return, are guaranteed full rights of ownership of their lands, forests, fisheries and other possessions; and Māori are given the rights and privileges of British subjects.”

When the document was translated to the Māori language, however, there were a few important distinctions:

“Most significantly, the word ‘sovereignty’ was translated as ‘kawanatanga’ (governance). Some Māori believed they were giving up government over their lands but retaining the right to manage their own affairs. The English version guaranteed ‘undisturbed possession’ of all their ‘properties’, but the Māori version guaranteed ‘tino rangatiratanga’ (full authority) over ‘taonga’ (treasures, which may be intangible).”

After the signing of the treaty, New Zealand officially became a British colony. British settlers traveled to New Zealand looking for land, opportunity, and a new start, and soon the settler population grew to outnumber the Māori. British culture became the dominant culture, and Māori were expected to assimilate.

In the 1970s, Māori and their supporters began to organize, protesting breaches of the Waitangi Treaty and arguing for Māori autonomy — a time now known as the Māori renaissance. In response, the government created the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975 to examine breaches of the treaty and investigate current claims against the Crown. In 1985, the Tribunal began investigating claims dating back to 1840. As of 2010, the Tribunal had settled claims with a value of about $950 million.

The renaissance also prompted an examination of the government’s relationship with the Māori, which led to calls for biculturalism in the public sector that spread through other realms of life, including religion. Māori was made an official language in 1987, and government departments began adopting Māori names alongside their English names. Successive governments through the ’80s and ’90s changed their approach to Māori-government relations to include the Māori perspective.

The shift to biculturalism has not been without critique. Some argue it is superficial and has not gone far enough; they want to see the development of Maori institutions and governance. Others argue New Zealand is now multicultural, and the focus on biculturalism leaves out those who have migrated from the Pacific region, known collectively as Pasifika, and other immigrants.

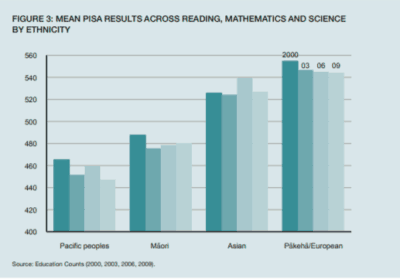

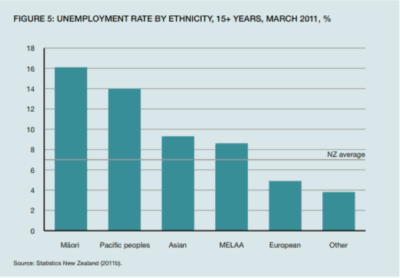

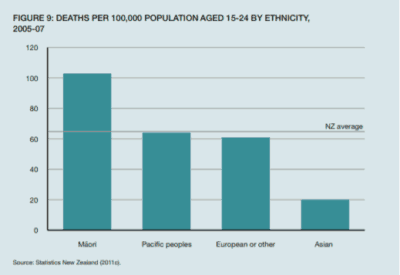

The focus on biculturalism also did not result in an improvement in education and health outcomes for Māori. Instead, Māori (along with Pasifika) continue to have significantly lower educational achievement, higher rates of dropout and unemployment, and poorer health outcomes than Pākehā/Europeans.

A 2011 report from the New Zealand Institute, a private, non-partisan think tank focused on improving long-term outcomes for New Zealanders, details the vast gaps in educational outcomes, employment, and health between Māori, Pasifika, and Europeans/Pākehā.

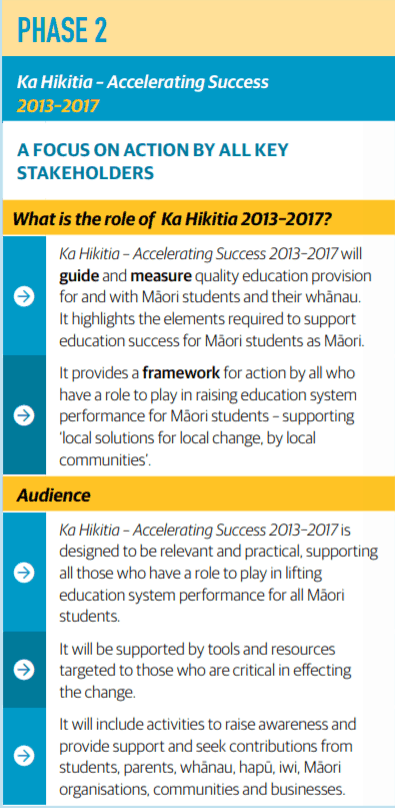

Following continued reports of the vast gaps in educational outcomes, the Ministry of Education launched a new strategy in 2008 to improve outcomes for Māori students through ensuring “Māori achieving success as Māori.” The strategy, called Ka Hikitia, has three phases: Ka Hikitia – Managing for Success 2008–2012, Ka Hikitia – Accelerating Success 2013–2017, and Ka Hikitia 2018–2022. The Ka Hikitia – Accelerating Success 2013–2017 report explains:

“‘Ka Hikitia’ means to step up, to lift up or to lengthen one’s stride. It means stepping up how the education system performs to ensure Māori students are enjoying and achieving education success as Māori.”

Achieving educational success as Māori is grounded in the idea that students should not have to abandon their culture and identity when they walk into the classroom. Because the education system in New Zealand is based on British cultures and norms, it values and prioritizes certain kinds of teaching and learning. For example, in many countries based on a Western style of education, learning is assessed through reading and writing. The Māori culture, however, has a strong oral tradition based on passing down stories and histories through generations, yet schools often do not offer Māori students a way to demonstrate mastery orally.

The graphic below is from the Accelerating Success report and outlines Phase 2, which aims to support key stakeholders to implement the strategy. Phase 3 envisions “sustained system-wide change” and Māori students achieving on par with the rest of the population.

Ka Hikitia has five guiding principles:

- The Treaty of Waitangi

- Māori potential approach

- Ako, the idea that teaching and learning is reciprocal

- Identity, language, and culture count

- Productive partnerships

In part three of the series, we will explore these five principles and look at Ka Hikitia in practice.

Editor’s note: The Oak Foundation supports the work of EducationNC.