Less than two decades ago, Hispanic and Latinx people accounted for 4.71 percent of North Carolina’s population. By last year, they made up nearly 10 percent. For rural areas, the increase has been even more dramatic, with rates often outpacing the national average. In towns like Robbins and Siler City, half the population is Hispanic. While growing diversity has been a boon to local economies, it has created new challenges and opportunities in schools.

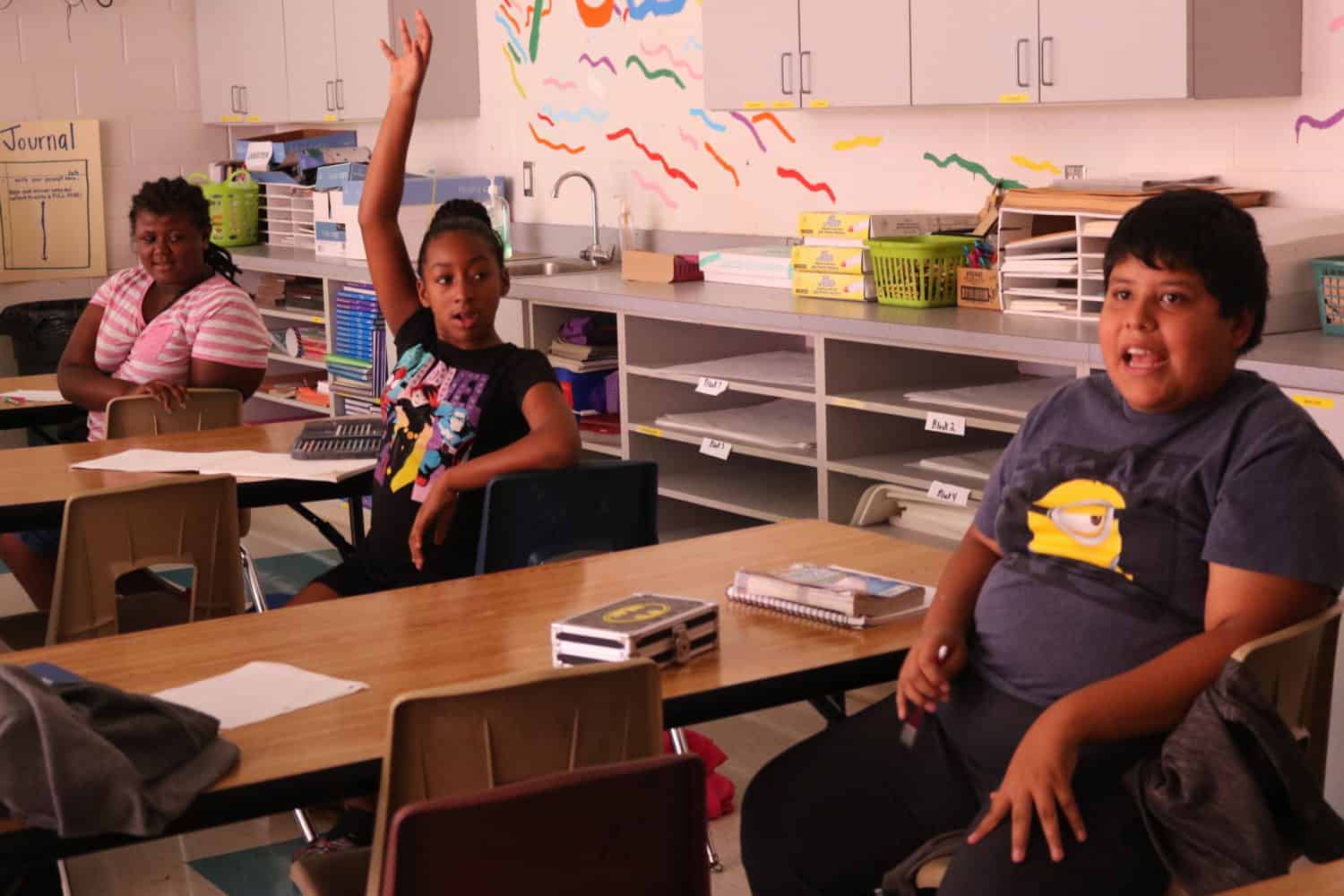

Teachers who once taught relatively homogeneous populations report being underprepared to support a classroom of students who are increasingly diverse, both culturally and linguistically. They may not recognize extraordinary academic abilities among students who are in transition—moving to a new town, a new form of schooling or even a new language. As a result, teachers and administrators are under-identifying Hispanic and Latinx students for gifted and talented programming.

According to North Carolina’s Department of Public Instruction, the rates of Academically and Intellectually Gifted (AIG) identification are inconsistent across racial and ethnic groups. Only 5.53 percent of Hispanic students in NC public schools were identified as AIG last year, compared with 12.52 percent of the total student body. Despite making up 16.7 percent of North Carolina’s total student enrollment, Hispanic students made up just 7.4 percent of students identified as AIG.

Research suggests that white students are 47 percent more likely to be selected for gifted programs than Latinx students. The rate of identification is even lower for English Language Learning (ELL) students. According to U.S. Census Data from 2014, 73 percent of Hispanics above the age of five spoke a language other than English at home. Because the process for identifying gifted students relies heavily on linguistic skills in English, or nomination by teachers and parents, very few ELL students end up in programs that recognize their high achievement – and potential.

Public schools in rural settings have long struggled with consistently identifying students for gifted programs and then providing them with appropriately challenging courses for reasons that include insufficient educator training and resources, underfunding of programs and even too few identified students to enable administrators to devote educators to traditional gifted and talented programs.

The problem grows more complex for rural areas with expanding Hispanic and Latinx populations. As educators develop their own skills to educate and support shifting student demographics, they focus first on essential academic capacities rather than identifying students for gifted and talented programs. Coupled with already limited resources, this leaves extraordinary students of color in the lurch.

North Carolina is far from alone in confronting this problem. The U.S. population is growing increasingly diverse, and Latinx people are moving to the U.S. at a rate higher than any other population. About 17 percent of the U.S. population is now Hispanic, compared to 12.5 percent in 2000. Between 1997 and 2014, the number of Hispanic students in the U.S. nearly doubled. There are about 13 million Hispanic students in U.S. schools. The success of Latinx students, increasingly, reflects the success of the United States.

We know that individuals with a bachelor’s degree earn about $2.27 million over their lifetime, or 74 percent more than those with just a high school degree. Those with master’s degrees earn $2.67 million over their lifetime. In majority-Latinx cities like Brownsville, Texas, low-income students are now more likely to perform at or above the level of their more advantaged peers, according to the Education Equality Index. Yet according to the Pew Research Center, just 15 percent of Hispanics ages 25 to 29 have a bachelor’s degree or higher. A recent report by the Latino Donor Collaborative predicted that by 2020, Latinos will account for 12.7 percent of the U.S. GDP, driving upwards of 25 percent of the nation’s economic growth.

Unless we attend to the problem of equity in gifted and talented identification, we are setting our economic future atilt. Some U.S. schools have already begun to address the discrepancy by re-thinking how they screen students for gifted programs. In 2005, schools in Florida’s Broward County school district began requiring that all second-graders take a nonverbal exam, rather than rely on teacher and parent referrals, for gifted classes.

Researchers at the University of California and the University of Miami then studied how the new process affected identification rates. For Hispanic children, the rate of students identified tripled, rising from 2 percent to 6 percent. At the time of the 2015 study, the screening process had identified 300 students who likely would have been previously ignored, including 240 students who were ELL or low-income students.

The researchers also found that Black and Hispanic students demonstrated large increases in math and reading skills when enrolled in gifted programs. While better identifying students of color for gifted and talented supports may not fully address inequity, it will go a long way toward expanding academic and economic opportunities for deserving students of every skin color.

Educators must not subscribe to the unfounded belief that limited English fluency denotes limited academic and intellectual potential. Missing out on identifying these high-potential students is a loss not only for the students but for economies like North Carolina’s and the nation’s at large.