|

|

On Oct. 28, over four weeks after Ashe County Schools (ACS) closed due to Hurricane Helene, Superintendent Eisa Cox chopped pork butts at the back of Westwood Elementary School. She and other district leadership were prepping a barbecue lunch for the entire staff — one last hot meal before students returned after 33 days away.

The principal of Westwood Elementary, Scott Grubb, smoked 14 butts and ribs, having arrived at his school at 4:30am to start cooking. He insisted it was a one man job up until the cutting and delivery.

At Ashe County High School, school staff were joined by central office, the bus garage, and the early college team for a joyous lunch. There was a round of “Happy Birthday,” folks adorned shirts boasting school spirit or “Ashe County Strong,” and a blessing reflected the gratitude and resiliency the community demonstrated during a devastating month.

“We thank you for this day, we thank you graciously for this group, for all those who prepared the food today. We thank you for the folks at Ashe County Schools,” Principal Dustin Farmer said. “Bless us this week as the kids come back.”

He thanked the staff for all their efforts, asked for blessings in his county and that they may all continue acting in service.

The Friday Helene hit, this same building was designated as an evacuation center. The elementary school where the barbecue was chopped was an emergency child care center prioritizing first responders’ families. The following day, another child care center opened at Mountain View Elementary School. Sunday after the storm, three schools became community distribution centers.

Like in many impacted regions, Ashe County public schools were the first line of defense during the crisis.

“Here’s the thing about being a teacher, being a school principal, being a superintendent — we make decisions all the time,” Cox said. “So even though we were not used to dealing in emergency management, we were used to corralling people together, making decisions, organizing big things. And I think that skill set translated to us being able to help out and lead in some of the recovery efforts that were happening.”

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Evolving recovery in Ashe County

On Tuesday, Oct. 8, three weeks before this meal, and not yet knowing when students would return, a meeting about reopening had just wrapped up at the ACS office annex in Jefferson.

Cox said her district would need everything in the package the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) had requested and more. A day later, the first of two hurricane relief bills passed and included almost everything the DPI asked for. The first included $273 million in relief; the second, passed on Oct. 24, included $604 million in relief.

Hurricane Helene relief bills

At the time, Cox said ACS had some water damage in schools, including leaks, flooded athletic fields, and destroyed computers, but nothing catastrophic. That said, returning to school wasn’t going to be simple. The biggest challenge, she said, was transportation.

The road network in Ashe County was hard hit, and in some places roads weren’t just closed — they were gone. Cox said on the 800 miles of roadways in Ashe County, there were more than 750 repair projects underway. After Oct. 8, that number grew significantly.

Cox, her Director of Transportation (DOT) Lisa Ashley, and district bus drivers have been on the road constantly to assess the safety and plausibility of regular routes.

There are still many obstacles to running regular bus routes, including unsafe bridges, obscured lines of sight, and single lane roads. In areas without cell service, which in Ashe County are common, the DOT cannot use timed stoplights to regulate roads that are single lane due to hurricane damage. School buses can’t take the risk of facing oncoming traffic.

And as the year continues, the sun is rising later and later — combined with repairs and winding mountain roads, resuming normal operations became a significant challenge.

The solution, which was put into practice Oct. 29, is adding in seven community stops to compliment regular bus routes. The district has worked with families to accommodate specific needs and will continue to adapt the best way to get students to school.

“Last week, it was going to be over 200 kids that needed a community stop, and we’re down to 88 today, which is absolutely huge,” said Cox of the repair work the DOT is putting in to make roads safe.

Cox, Ashley, and Director of Technology Amy Walker joined together in the Creston Superette parking lot — one of the community bus stops — to welcome students back on Tuesday morning. Some families have to drive anywhere from 20 to 30 minutes to get to this stop, but it’s as far as a bus can go up the road.

The morning sun didn’t rise until 7:46 a.m., and a thick fog settled in the valley. Buses were warm, drivers were excited, and students walked on, not dragging any feet.

Cox knows of at least 25 students who are now without a home, and many families that have lost cars or their places of business. While there is a long road to recovery, this community bus stop is offering a ride back to some routine and support systems.

“I have two big takeaways. One, we have a really strong community here, western North Carolina, northwest North Carolina is very resilient. And it was really the community that pulled together in order to make it happen for each other,” Cox said, reflecting on the last month.

“And number two, the importance of public education. Had we not had these buildings, had we not had our structure, the togetherness, the wherewithal to be able to solve problems, it would have taken a couple of weeks to pull those community systems together. And I think that because we had the people that were used to making decisions, we had the systems of communication that were already in place, and we all have a servant’s heart, and I think that servant nature of pulling together for community was really powerful. Had we not had that system of public education, it would have been really tough to pull together.”

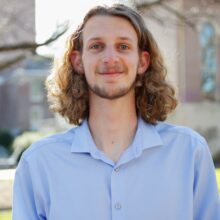

Eisa Cox, superintendent of Ashe County Schools

Recommended reading