Share this story

- Beyond LETRS, the science of reading law addresses how teacher candidates are prepared, expectations for early literacy instructors, and how intervention plans should look.

- "It’s a process, so we knew this wasn’t going to change overnight,” State Superintendent @CTruittNCDPI said. “We’re going to keep supporting districts throughout implementation of the law.”

Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS) training is the most recognized aspect of North Carolina’s year-old science of reading law. It’s the squeaky wheel on the axle of the Excellent Public Schools Act (EPSA) — and the early response from teachers is mixed.

With all the talk about whether it’s worth it and whether it ought to happen now, it’s easy to forget that LETRS is just one component of a comprehensive legislation aimed at eliminating poor reading practices once rampant in the state.

Beyond LETRS, though, the law addresses how teacher candidates in North Carolina’s institutions of higher education are taught, the expectations for early literacy instructors, and how intervention plans for students should look.

Like LETRS now, the EPSA drew mixed reaction from education stakeholders when Senate President Pro Tem Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, spearheaded it through the legislature and Gov. Roy Cooper ultimately signed it one year ago. With the General Assembly expected to revisit funding for the law during this short session, it’s worth a look at what’s happened the last year and what’s set to occur.

Has literacy instruction improved yet?

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Catherine Truitt said she’s seeing marked improvement in her travels across the state, but admits there are still some visits where she sees persistent use of balanced literacy curriculum and poor instructional practices.

“It’s a process, so we knew this wasn’t going to change overnight,” she said. “We’re going to keep supporting districts throughout implementation of the law and I expect that we’ll see a lot of progress by the time this is fully implemented.”

Most recent student data available is from middle-of-year assessments this school year. They show an aggregate 10-point bump from troubling beginning-of-year scores, which state leaders attributed to time out of school during the height of the pandemic. It’s too soon to link improvements to the legislation, state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) leaders say, because much of the law is yet to take hold in districts.

According to the deadlines in the law and DPI’s internal deadlines to meet the law’s requirements, full implementation is not expected until the 2024-25 school year.

Even then, full implementation is only required at traditional public schools as legislators declined to include charter schools under the law’s mandates. That means charter school teachers aren’t required to do LETRS training, nor are charters required to submit literacy implementation plans or literacy intervention plans.

As for implementation timeline, the last cohort to complete LETRS training won’t do so until 2024. Prior to that, institutions of higher education will have implemented their literacy frameworks for preparing future teachers and DPI will review literacy implementation and intervention plans for every district.

Does everybody in traditional public schools know the science of reading?

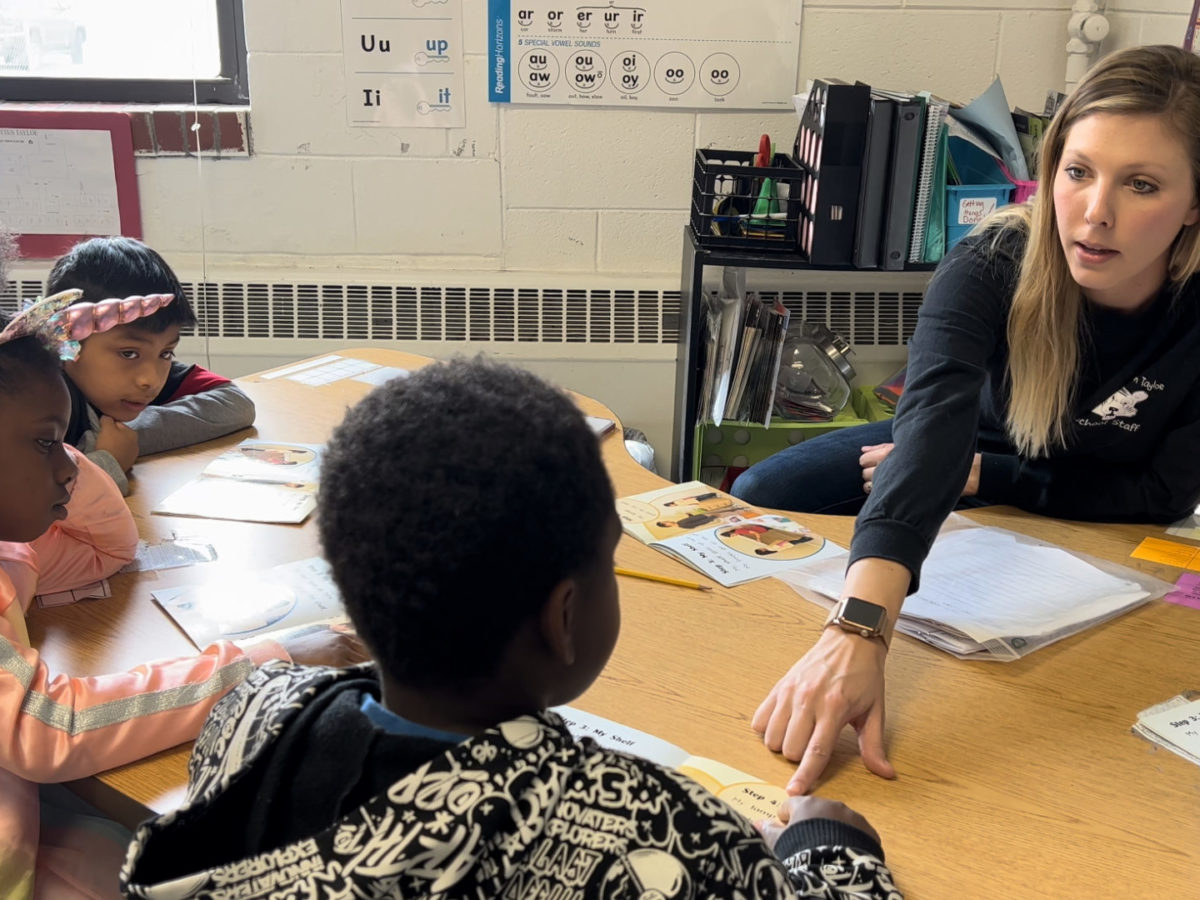

The law doesn’t provide a quick fix. Instead, North Carolina’s focus is on making sure educators are starting with the same foundational knowledge, able to instruct students regardless of the curriculum in their schools, and building a shared vocabulary for reading instruction across every district.

With the exception of LETRS, which is named in a budget bill that the reading law references, the EPSA avoids relying on specific vendors to achieve its goals. Instead, Berger (the bill’s sponsor) said the law is a roadmap for building teacher knowledge and providing state-level guidance.

In order to help districts, and especially teachers, align practices with the science of reading, DPI has created literacy instruction standards for pre-K through 12th grade, a model implementation plan to incorporate those standards, a “non-model” that shows districts what DPI discourages, and guidance on literacy interventions.

Meanwhile, educator preparation programs in both the University of North Carolina System and North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities (NCICU) have literacy frameworks to help ground instruction of teacher candidates in the science of reading.

Has the state selected a curriculum that aligns with the science of reading?

DPI has not indicated any intention to select or endorse curriculum — that choice will remain up to district leaders. When the State Board of Education (SBE) convened its literacy task force in 2020, the group tackled the issue of curriculum and instructional materials. In its June 2020 report, it recommended the state define criteria for selecting instructional material and allocate funding only for evidence-based resources.

That’s what the literacy instruction standards and literacy intervention standards process is aimed at doing.

In October 2021, SBE approved a set of literacy instruction standards. These are different from the state standard course of study — which communicate expectations of what students must learn. Literacy instruction standards communicate expectations of what teachers must teach.

“These are essential, non-negotiable methods of teaching literacy that sets a level of quality for instruction,” Kristi Day told educators during a DPI webinar last summer. Day is assistant director of academic standards, the division which — in collaboration with the Office of Early Learning, literacy experts, researchers, and educator preparation faculty — is preparing the literacy instruction standards.

“The expectation would be that these are consistently implemented in every classroom throughout the entire state,” she said.

See the draft literacy instruction standards

The model and non-model literacy implementation plan from DPI will go out with the literacy instruction standards and offer guidance for incorporating the standards into curriculum and instruction. This week, SBE approved changes to the literacy instruction standards, which now include guidance on best practices, as well as the implementation plan.

These documents will go to the Joint Legislative Education Oversight Committee and, upon approval there, would be sent to districts by the end of June. Districts must submit their own literacy implementation plans to SBE by Dec. 15 and will receive feedback and modification support from DPI by Nov. 15, 2023.

Have interventions and summer reading camps changed?

This is an open question that won’t be answered until summer 2023, though districts were provided templates for literacy intervention planning. Districts were required to submit literacy intervention plans this spring and will receive feedback from DPI in May — ahead of this summer’s reading camps.

The literacy intervention plans are created by districts and meant to document the interventions used, include protocols for Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) alignment, and communicate summer reading camp programming.

Districts will have time to incorporate DPI feedback into this summer’s camps and are expected to submit final plans in October. DPI will report on approval or denial of plans in Feb. 2023 and districts may submit amendments, if necessary, in March. In April, districts will be notified of final approval or denial. At that point, state literacy intervention funding — which includes funding for summer reading camps — will be tied to DPI’s approval of the plan.

This process will repeat annually.

DPI Literacy Consultant Kelly Bendheim said this phasing and feedback process is intended to allow districts to try out new things as they progress through LETRS training, and have multiple opportunities for feedback and data evaluation.

“If we think about implementation science, what [educators] are being afforded this first year is the opportunity to explore, then installation, and then initial implementation,” she said. “[It] allows time to plan interventions before implementation.”

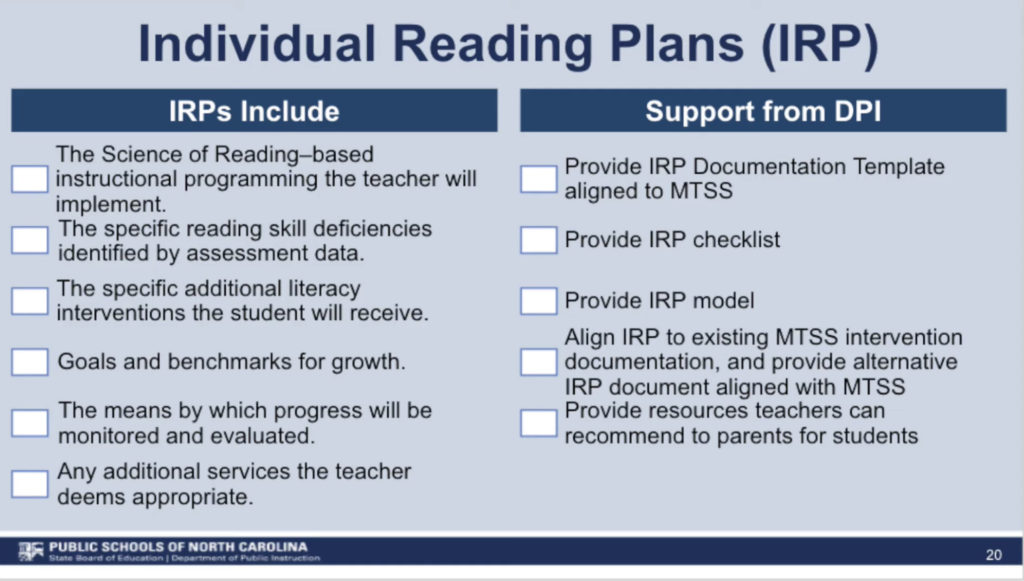

The law also mandates individual reading plans for every student. These are created by teachers and document the literacy interventions for each individual student, as well as set goals and plans for progress monitoring.

“These plans are, essentially, the literacy intervention plans in action,” Bendheim said. “So while the literacy intervention plan is the design and the preparation, the individual reading plan documents the intervention plan at the student level.”

Both the intervention and individual reading plans are aligned with MTSS, DPI leaders say.

“Our hope is that you can see there is alignment here between current practices and this legislation,” Bendheim said. “We’re not having to reinvent the wheel.”

Whatever happened to coaches in low-performing schools?

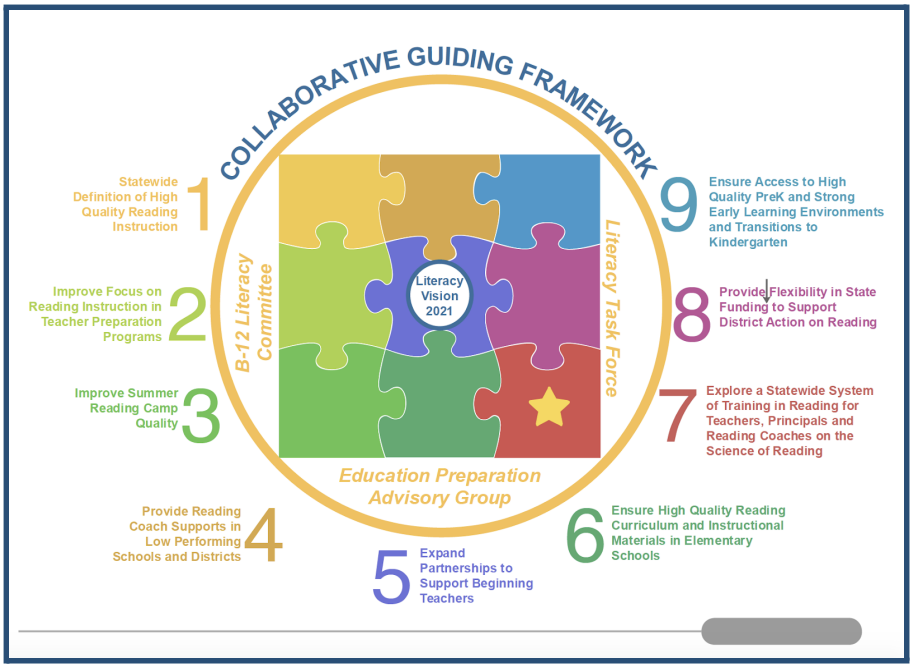

The state’s shift to the science of reading began in 2017 with the UNC System, and by 2019 — almost two years before enactment of the EPSA — DPI and SBE created a Collaborative Guiding Framework for Early Literacy Education.

The framework is built on nine core elements, many of which are addressed in the EPSA. One element that is not explicitly covered in the law, though, is providing reading coach supports in low-performing schools and districts.

Last summer, DPI’s contract for LETRS was delayed because the agency wanted to include existing elementary instructional coaches (as well as English Language Learner and Exceptional Children teachers) in the training. But, thus far, DPI has not publicly released a plan for school-based coaches in high-need schools, nor has the General Assembly given indication for funding one.

What’s happening with EPPs?

The law’s mandate that educator preparation programs (EPPs) providing training for elementary and special education teachers receive instruction aligned with the science of reading takes effect for institutions applying for or renewing approval on or after July 1.

In preparation to meet that requirement, the UNC System has created and adopted a literacy framework for preparing future reading teachers. The NCICU is also working on its own framework.

Starting in 2021, some community colleges began offering associate degrees in early education. As part of this coursework, students are required to take a course on the science of reading.

The Reading Foundations teacher examination, which is required for teacher licensure, is also being updated to exclude testing on practices that research has established as poor and to include concepts aligned with the science of reading.