When lawmakers put $35.4 million into principal and assistant principal pay raises during the 2017 long session, it was a move that was a long time coming. Advocates of principals lauded the long-awaited raises, as well as the restructuring of the principal pay schedule.

“Fundamentally, it is a light years improvement over what we had,” said Brenda Berg, president and CEO of Business for Educational Success and Transformation (BEST NC) — a bipartisan, nonprofit group of business leaders.

The General Assembly went on to increase their investment by adding another $12 million to that pot for principals alone during the 2018 short session.

But gradually, as the new principal pay schedule has begun to be implemented, criticisms have emerged.

While many principals receive pay raises under the new schedule, some — the ones at the top of the food chain — don’t. They would actually receive less except that a hold harmless provision in legislation says that they will continue to make what they made before if they stand to take a pay cut under the new schedule. That hold harmless provision wasn’t indefinite, however. At first it was only one year. Then in the short session, another year was added. Advocates worry that eventually, the hold harmless won’t be extended and some top-paid principals will lose money and perhaps leave the profession or retire as a result. That remains to be seen.

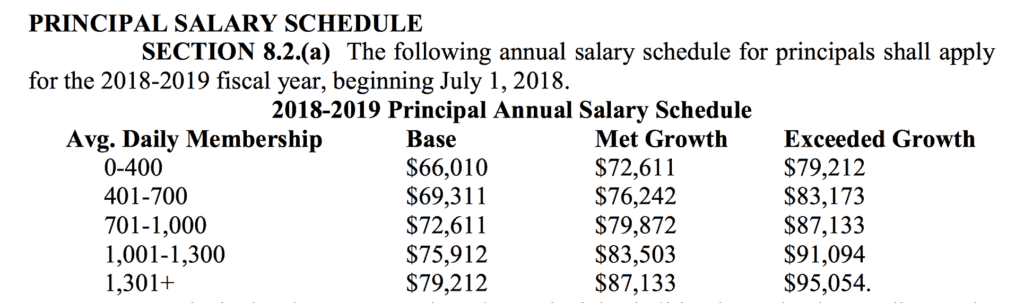

Another criticism is that the new principal pay schedule encourages principals to work at schools with high academic growth. Basically, a principal gets a base salary based on the size of his or her school. Then he or she gets a little more money if the school meets academic growth. And the principal gets even more if the school exceeds academic growth. Critics worry that this will discourage principals from working at low-performing schools, often the ones most in need of strong leadership but least likely to achieve stellar growth.

Also, years of experience have been taken out of the calculation of principal pay, and there are some principal advocates who would like to see that returned as part of the formula. The removal of longevity pay and extra pay for advanced degrees is also sharply debated.

While there are surely improvements that need to be made to the principal pay schedule, it’s important not to lose sight of the strides North Carolina has taken. And it’s not just that the state has put more money into principal pay. It’s that lawmakers reformed a principal pay model that was burdensome and overly complicated.

The very first article I ever wrote for EducationNC was about the problems with the principal pay schedule.

I led that article with Katie McMillan, a principal with 15 years of experience at Centennial Campus Magnet Middle School in Raleigh. She started her job in 2014 without realizing that under the old pay schedule, she wasn’t due to get a pay bump until 2019.

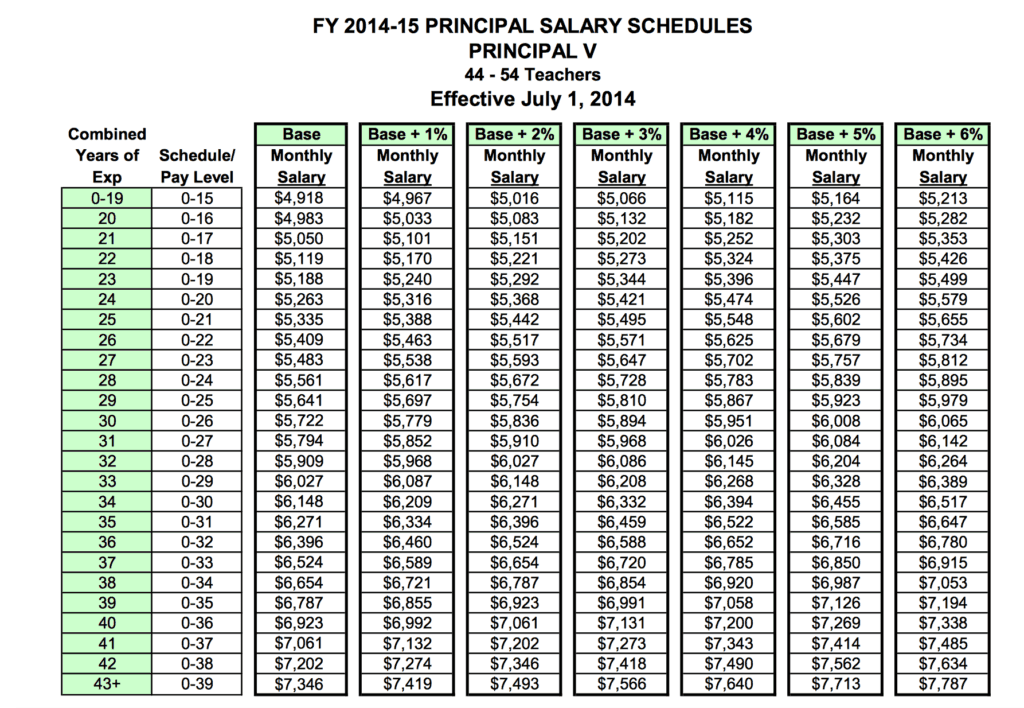

The old principal pay schedule was intense, to say the least. There were eight different charts for different levels of principals, each with more than 20 steps. Principals could get extra money for an advanced degree, a doctorate degree, because they had been around since now-defunct incentive programs were instituted, and based on their years of experience. Here is the pay schedule that McMillan was on.

For principals in the category in the above chart, the first level of pay was $59,016 a year. That’s a base level for all principals on the chart who had a range of experience between zero and 19 years. That means that a principal would have to wait until their 20th year of experience to get a pay bump.

That was just one problem. There were many others, some that are still being worked out. The principal pay schedule was out of sync with the teacher schedules, some teachers were paid more than principals, and it was just confusing. That chart up there, remember: there were seven more of those just for principals.

For context, here is the entirety of the new principal pay schedule.

Simple, right? And with the pay raises, it set North Carolina principals in a different direction.

Prior to 2015, when I wrote my article on the problems with the principal pay system, principals got relatively short shrift. There were regular increases in principal allotments from the General Assembly since 1993, but they were mostly cost-of-living increases rather than actual raises, according to a DPI staffer I talked to for the 2015 article. And in 2009, after the economic recession hit, pay for principals was frozen through 2013 with the exception of a one-time 1.2 percent salary boost in 2012.

Before the pay boosts in 2017 and 2018, North Carolina principals were ranked 50th out of all the states and Washington, D.C., for principal pay. It may be too soon to know whether we’ve moved up in that ranking, but at the very least, by increasing pay overall, we shouldn’t be getting worse.

Under the new pay schedule, there aren’t regularly scheduled pay bumps as under the previous step-based system, but so far the General Assembly has shown a willingness to keep devoting money to pay increases. And with the incentive system, principals have the ability to increase their own pay based on performance rather than just the passage of time. One can debate the wisdom of that structure, but it does offer a pathway to greater pay.

Whatever one wants to say about how lawmakers are handling the principal pay situations, they are trying to make it better. The principal pay schedule had stagnated for years prior with seemingly no legislative interest in changing it. It persisted under both Democratic and Republican control of the General Assembly, and under the administration of governors of both parties. Since 2017, lawmakers have finally started to do something.

“There is no evil intent on principal pay…” said Rep. Craig Horn, R-Union at one point. “Legislation is not an exact science. We do things that we think will help solve an issue.”

And this is all important because, as is said again and again in education circles, principals are one of the most important people in a school building.

“School leadership is second only to teaching among school-related factors in its impact on student learning, according to research,” a report from the Wallace Foundation, a national nonprofit working on school leadership, stated. “Moreover, principals strongly shape the conditions for high-quality teaching and are the prime factor in determining whether teachers stay in high-needs schools. High-quality principals, therefore, are vital to the effectiveness of our nation’s public schools, especially those serving children with the fewest advantages in life.”

Illustrating this is a new special report from Education Week: Principals Under Pressure. In it, Education Week explored the biggest challenges facing principals. “Safety, student mental health, dealing with toxic employees, handling the complex needs of special education students and their families, holding on to the best teachers, and time management and work-life balance” were the ones that Education Week heard about repeatedly, and their report as well as the series of articles linked in this paragraph have a wealth of information for and about principals. I encourage you to read it.

Here is what Education Week had to say in its introduction to the special report:

“Is there a job in K-12 education more demanding and complex than the principal’s? We’d argue there’s not. Principals have to answer to the central office. They need to be responsive to parents. They must make teachers their top priority — to be instructional leaders. And of course, they must build relationships with students. How is doing all those things successfully even possible when principals must also grapple with some of the most vexing challenges in our broader culture that spill over into schools every day?”

While North Carolina, no doubt, has a long way to go to address all the challenges principals face, by transforming the principal pay schedule, it has begun to move in a new direction. One with room for improvement. But it’s a first step.

Now there are some grumblings and rumblings that the extra money isn’t actually making it into our principals’ pay checks. I am checking into it, and I’ll let you know what I find.

Notable news

According to research from North Carolina State University, Read to Achieve has not had any effect on reading scores for the first two groups of students to go through the program.

Read to Achieve is a state program that tries to improve reading ability for third-grade students. It has been around since its implementation in 2013. Read the research for yourself here.

In other news, the Innovative School District (ISD) has chosen Carver Heights Elementary in Wayne County to be the second school to join the ISD.

The Innovative School District is a program that will ultimately take five of the lowest-performing schools in the state and put them in a virtual district. The schools will still be located where they are currently, but they will be taken over by outside operators, which could include for-profit charter or education management organizations. The schools will have charter-like flexibility and the district will be overseen by the ISD.

This fall, Southside Ashpole Elementary in Robeson County, became the first school to open its doors as part of the ISD. Carver Heights will join it next fall.

Lastly, the final school district in the state that uses corporal punishment has voted to end the practice. Graham County Schools Board of Education voted earlier this month to end the use of paddling as a punishment in its schools, meaning that corporal punishment is now gone from North Carolina.