This August as schools geared up for another year, the Brookings Institute published two studies that address the diversity gap in the teaching workforce. Only 18 percent of American teachers are minorities, while half of public school children are. Does that matter?

The authors of “High Hopes and Harsh Realities” and “The Many Ways Teacher Diversity May Benefit Students” argue that it does.

All of us, whether we admit it or not, see the world through lenses particular to race, sex, and culture. Our expectations of other people’s behavior are based on who we are.

In the complex interactions between teachers and students, those biases affect how our students feel about school and how well they do there.

White teachers are more likely than black teachers to judge their black students as inattentive or misbehaving. They are less likely to recommend minority students for gifted programs.

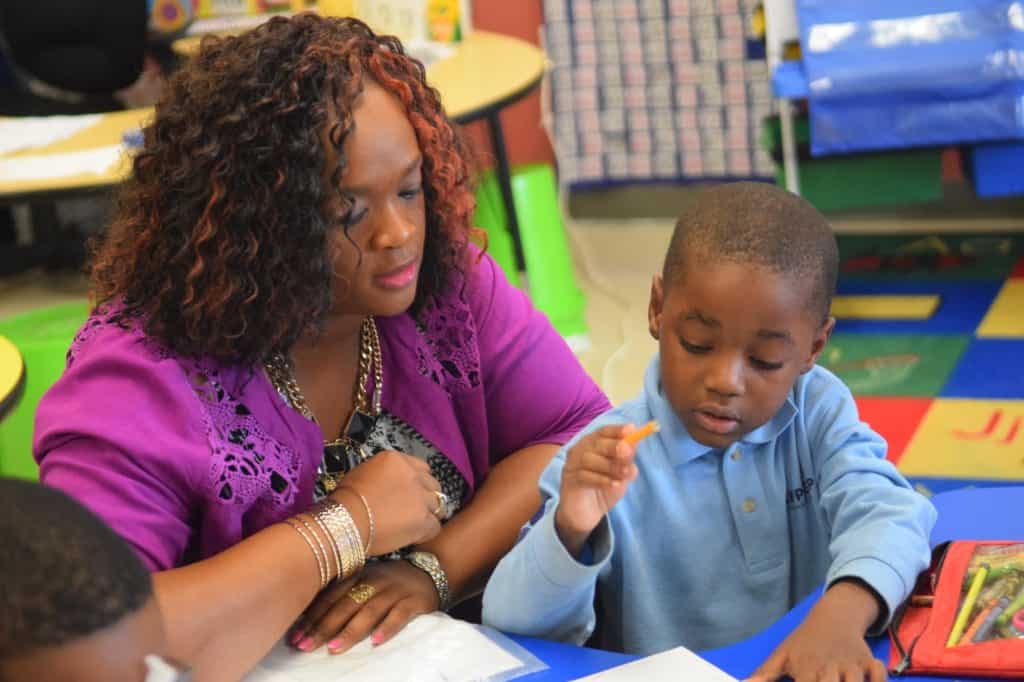

Minority students taught by minority teachers miss school less and are suspended less than minority children taught by white teachers. They report more positive feelings about their teachers and look up to them more readily as role models.

Teachers – myself included – might bristle at those findings, but ignoring them is naïve. I remember one afternoon as some fellow teachers and I – white women all – stood in the hallway discussing how we see our black male students differently since Ferguson. That knot of football players laughing and teasing each other about the upcoming game, ducking pretend jabs as they make their way to their honors English class? Would someone who doesn’t know them be alarmed at their noise, see them as a threat? Standing there, we admitted that we worry about them in a way we didn’t before, see them as vulnerable to misunderstanding and violence, the way their parents – and black teachers – always have.

Increasing the number of minority teachers is difficult. A smaller proportion of black and Hispanic students attend college than do their white peers, and they indicate less interest in teaching. Those that graduate with teaching certificates are hired at lower rates than white graduates and leave the profession sooner.

Which means that few students have black and Hispanic role models for teachers, and the cycle repeats itself.

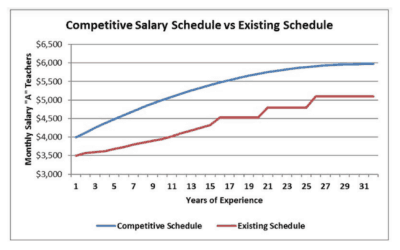

Increased college and career recruiting and district policies to hire and retain minority teachers help, but narrowing the gap in a significant way is daunting. Indeed, teaching as a profession is less appealing for any potential candidates than it was in the past. The researchers highlight the negatives – such as the absence of teacher voice in decision making, harmful testing and evaluation policies, and relatively low pay – as factors.

But a more diverse teaching population would benefit the profession as a whole. What would the pay and working conditions be if the majority of teachers weren’t female, for example?

Despite the difficulty of narrowing the diversity gap, we aren’t helpless. Acknowledging our biases and our tendency to stereotype is the first step to being more effective with all our students. Teachers and students who share no trait in common can be terrific partners in learning. Those relationships can be exceptionally strong – forged out of a respect and celebration for each other’s differences.

At every meeting before school officially opened, my principal exhorted the faculty to get to know our students. That’s a potent antidote to a lack of diversity in education. When we know our students as individuals, we commit ourselves to doing what is best for each and every one of them.