When schools shut down for in-person instruction back in March because of the COVID-19 pandemic, nobody thought it would be almost seven months before students would be able to return to the classroom full-time, but that’s exactly what happened.

Schools went remote for the remainder of last year’s spring semester, an experience that was often frustrating for students and teachers alike. Then, much of the summer was spent wrestling with the various ways schools could return this fall: from all remote learning, to all students back in class, to a hybrid approach.

Ultimately, Gov. Roy Cooper announced schools would begin in August with a hybrid model, though districts could also choose a fully remote option, and parents would be given the choice of having their student be remote even if in-person instruction was offered.

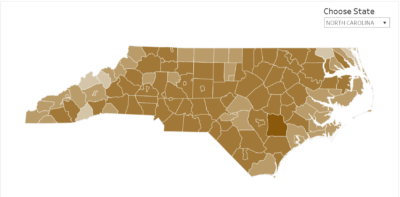

Most students in the state started out with some form of remote learning, but gradually, more and more districts have either begun or are scheduled to venture back into the classroom under a reduced capacity.

Then, in September, Cooper said that districts could have K-5 students come back for in-person instruction full time.

Now, today, for the first time since March, districts are able to allow all elementary school students back into the classroom if they want to.

Here’s a look at what we know so far about which districts are choosing to go back to elementary school full-time time. This is called plan A. Plan B is a hybrid model, and plan C is the model where all students are doing remote learning.

This week, we are taking a look at the various factors that go into making decisions about bringing students back into school buildings.

Liz Bell will be writing what we know about the science. Caroline Parker will profile Perquimans County Schools, which was one of the only districts in its region to start out the year in plan B, and which has already decided to move to plan A starting the week of Oct. 19. Her article also looks at how Perquimans County Schools used parent surveys to inform their process. And we’ll release a database in partnership with Public Impact that details what approaches K-12 districts are taking this fall, including how they’re providing instruction, school meals, and more.

But before those pieces roll out, let’s take a look at some of the other influences that have and continue to impact how these decisions are made.

What role does the governor, data, teachers, ethics, and peer pressure play on whether or not students go back into schools?

The governor

There is, of course, no single person with greater power to influence what happens in schools during this pandemic than Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper.

He is the only one in the state who possesses the power to take certain actions that are needed during a state of crisis. The Education Commission of the States says that “only a governor can marshal state agencies to:

- “Review and streamline eligibility requirements.

- “Provide license reciprocity for educators, social workers and other student support professions with shortages in existing talent.

- “Direct agencies to blend funding revenue from federal and state sources like Medicaid, WIOA, ESSA and others so all dollars are working toward the same goal.

- “Facilitate data collection, sharing and analysis.”

He is also the only one who can decide on his own whether students can actually go to school buildings or not.

It was his executive order that took students out of school in March. It was his decision over the summer that schools could choose to open in the fall under the hybrid (plan B) model or just with remote instruction (plan C). And it was his decision in September to allow elementary schools to open up fully starting Oct. 5.

His decisions have not been met with universal acceptance. Legislative Republicans and other GOP leaders have been challenging the logic behind his decisions for months.

Indeed, his announcement that elementary schools would be able to reopen came only one day after a press conference held by Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, the Republican candidate for governor, Lt. Gov. Dan Forest, and the Republican candidate for state superintendent of public instruction, Catherine Truitt. At that press conference, the Republicans demanded that Cooper offer a full-time in-person instructional option for students.

The governor’s decision the next day regarding elementary schools came as a surprise to some.

Regardless, it is Cooper’s decisions that set the stage for what is happening in schools. The rule is that districts can choose a more conservative approach to instruction but not a more lenient one. So, right now, middle schools and high schools have the option of a hybrid approach, with some students in school and some students remote. Districts can also choose to do all remote instead. But they cannot choose to allow all students into school.

Similarly, while elementary schools are allowed to let all students back into schools, they are by no means required to. They can do a hybrid or all remote model as well.

As the year continues, it will be the governor who ultimately decides when schools can fully return back to normal, so districts will continue to look to him for an indication of what their future holds.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Data

Another factor influencing districts’ decision on when, how, or if to bring students back into the classroom is what is happening with COVID-19 in their county as well as their relationship with their local health department.

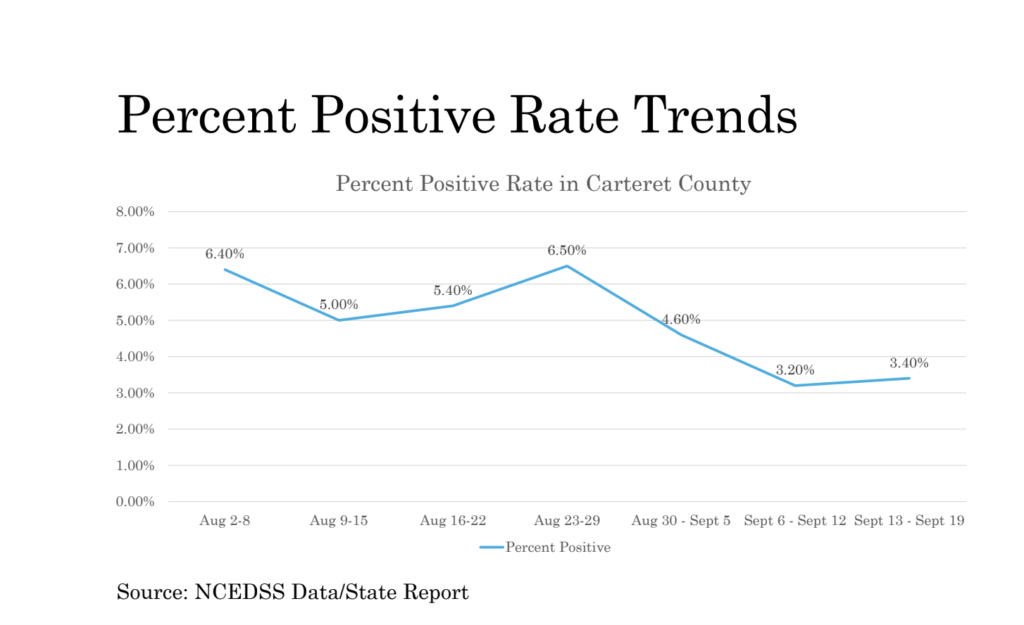

For instance, Carteret County’s Board of Education voted last week that elementary school students in the district can return to school starting Oct. 19.

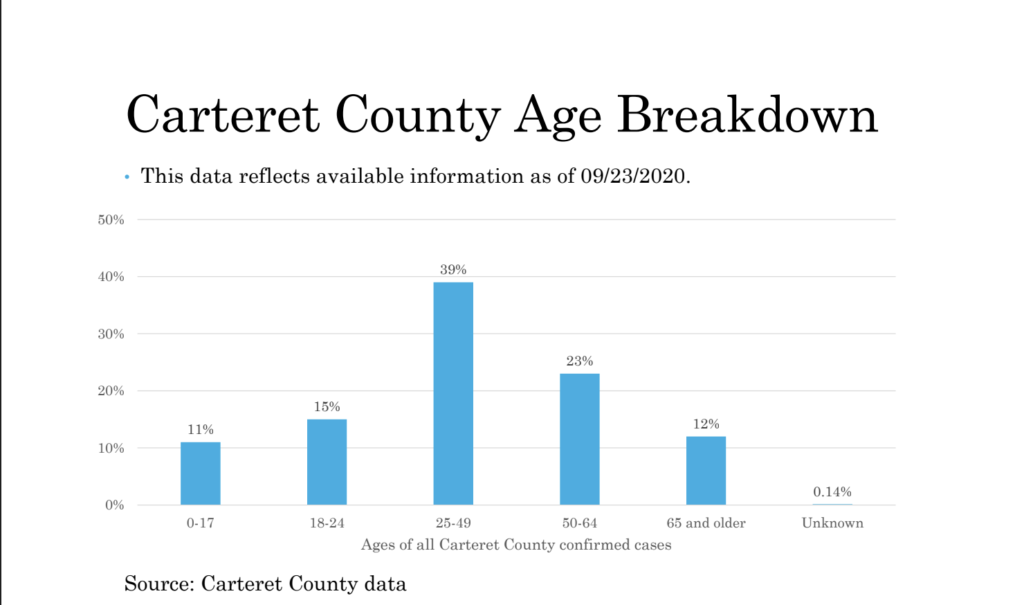

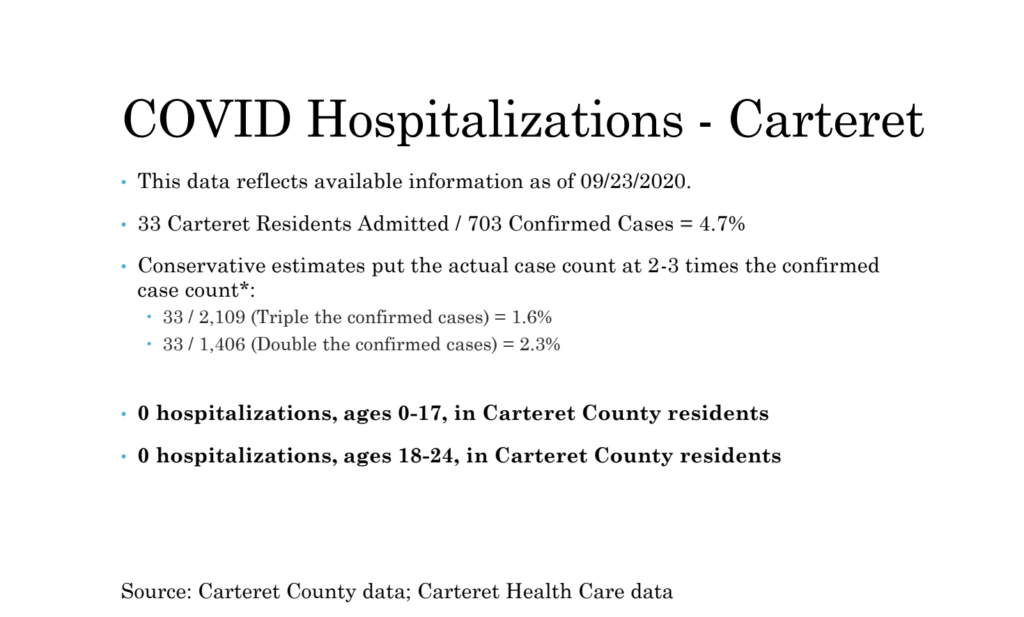

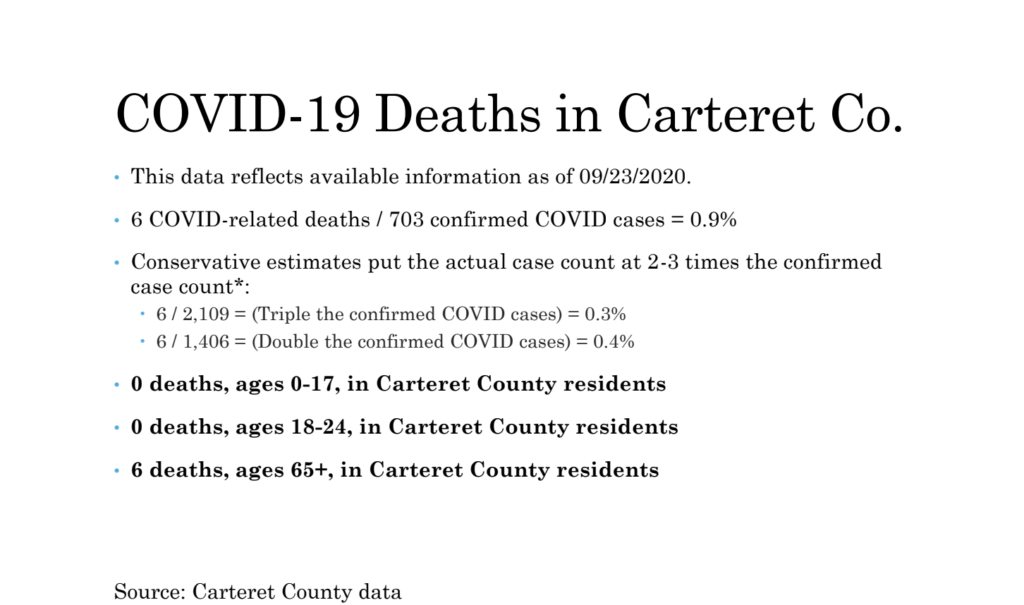

Stephanie Cannon from the Carteret County Health Department gave the following presentation to school board members laying out the situation with COVID-19 in the county.

Included in the presentation was data on the declining percentage of positive cases of COVID-19.

It also included data on the low incidence of infection among the young.

And it detailed the low number of hospitalizations and deaths among youth in the county.

So, sometimes data can be a source of safety and security, helping a district decide what they can and can’t do. Other times, it can be a source of frustration, particularly when a district leader thinks the data says one thing and the rules are saying another.

During a recent visit EducationNC made to Perquimans County Schools, Board of Education Member Matt Peeler expressed some of that frustration.

According to the state’s Department of Health and Human Services COVID-19 Dashboard, the county has had 189 cases of COVID-19, putting it in the lowest category in the state as far as outbreaks are concerned. Peeler said the current positive case count is even lower, and he doesn’t understand why his district has the same set of options as other counties, such as Wake County, which has had more than 17,000 cases.

“It’s not prevalent in our community, so why should we be held as though we are in a high-transmission place?” he asked.

Earlier in the discussion, he said he wished the governor would give more flexibility to districts.

“Empower us to be school boards and represent our communities,” he said. “That’s what I’d really like.”

And then there is the impact that COVID-19 has on schools once they do open for in-person instruction. In Rockingham County, for example, schools only recently opened under the hybrid plan B model.

And now, because of COVID-19, three schools have to close for two weeks. And this isn’t unique to Rockingham County. It’s happened in Cleveland County and in Guilford County, and no doubt elsewhere. And it will likely continue. It is the nature of education in a pandemic.

Teachers

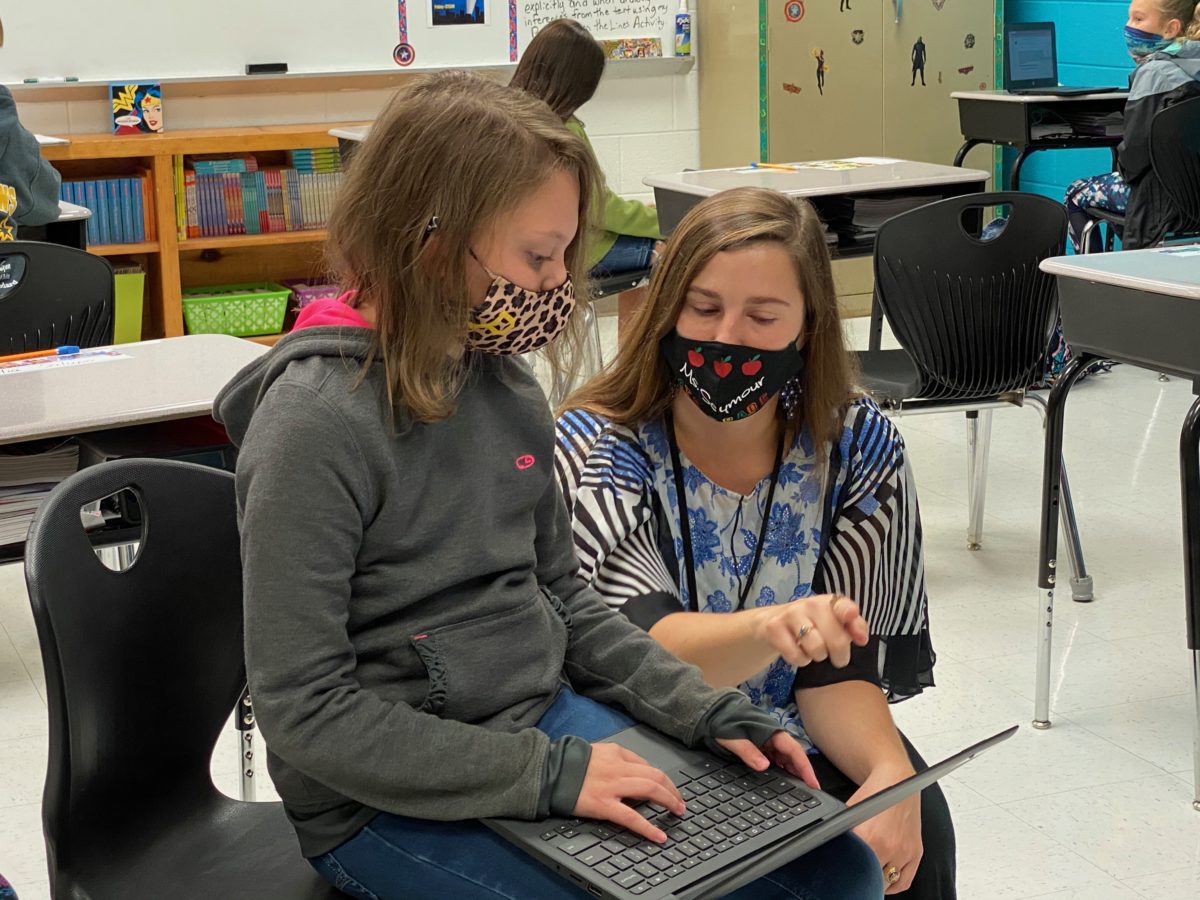

When it comes to letting students back into the school building, not everybody is on the same page. As we’ve seen, different members of North Carolina’s education leadership have conflicting opinions about what’s safe and what’s not. The same is true at the district level. Sometimes teachers, in particular, have a powerful voice in determining when and how students return to the classroom.

For instance, in Edenton-Chowan, the elementary school leaders were ready to take Cooper up on his offer to let students back into schools full-time. EducationNC reporter Liz Bell wrote about what happened. Here is what Sheila Evans, the principal of White Oak Elementary, had to say at the time.

“We were like, oh yeah, plan A, let’s do it. Because we can fit, and we can do it,” Evans said.

But according to Bell’s reporting, everything changed by one week later. Evans and other district elementary leaders decided to stay in plan B, the hybrid model of instruction.

Bell explains that part of the change was because of discussions with teachers. One of those teachers was Lisa Chappell, a veteran kindergarten teacher. She told Bell that the transition to kindergarten is tough in a normal year. And this year isn’t normal.

“You’re asking me to start it at the beginning, you’re asking me to start in October, and you’re asking me to start again in January when they all come back,” Chappell said. “That’s three starts to a school year. That’s a lot for a teacher. You’re adding one little lump of new people now; you’re going to add another lump of new people later. That’s hard.”

This is a story playing out across the state. Durham Public Schools recently decided to stick with plan C — all online learning — into 2021.

ABC 11 quoted Superintendent Pascal Mubenga as saying the following: “Our community and teachers are not all of one mind, but right now most families and teachers still have deep concerns about COVID-19. We are continuing to work with our health department and medical experts to identify the best, safest time to re-open for in-person instruction. Our students need in-person instruction, but parents and teachers need to be confident that our community is ready. I will always consider their health and safety first.”

Even the North Carolina Association of Educators, which usually supports Cooper’s decisions, has been fighting back on his plan to allow elementary school students back into schools full-time.

Peer pressure

Perhaps nothing is so likely to influence a person than the actions of his or her peers, and that remains true even when a person is all grown up. Superintendents in North Carolina have their own term for it, according to Greene County Superintendent Patrick Miller: The snow day effect.

As the name implies, the origin of the term comes from weather-related events and how districts make a decision to close schools.

“When everybody around you is shutting down based on a forecast … and you’re an island in the sea, so to speak, you put yourself at risk,” Miller said.

Basically, if all the districts around you are closing because of inclement weather, a superintendent is really going out on a limb to keep his or her schools open.

Over the summer when districts around the state were deciding whether or not to start the school year in the hybrid or remote learning model, the pressure was on for people like Miller.

His district is surrounded by Wilson, Wayne, Lenoir, and Pitt counties. All but Pitt were planning to open with remote only. Greene, however, decided to go with the hybrid model.

“That put undue pressure on us, but we stuck with it,” he said. “And now, it will be interesting to see if there is any ‘snow day effect’ as districts transition to plan A.”

Another aspect of all this is what happens when the superintendent of a school district and the board of education disagree.

Miller said that while he and his board were on the same page, that’s not true of everyone.

“The board of education is the final decision maker,” Miller said. “The superintendent makes a recommendation and it’s up to the board of education to accept, reject, or modify that recommendation.”

Over in Lenoir County, the district staff and school board did not agree. During the summer, Superintendent Brent Williams and his staff were recommending to their board of education that schools spend the first four weeks of the semester in remote learning and then have all grade levels return to school using a mix of in-person and remote instruction.

With a 4-3 vote, the board of education voted instead to have all students do remote learning, saying it would be at least nine weeks before any students returned to classes.

The district ultimately launched its hybrid model on Sept. 28.

Ethics

There is also an ethical component that comes into play when leaders are making a decision about whether students can come to school in person.

John Hopkins University put out a white paper entitled: The Ethics of K-12 School Reopening: Identifying and Addressing the Values at Stake.

In the paper, the writers explore why making decisions about young people is morally complex. They write:

“Children hold a unique place in society. They are morally special for two important reasons. First, children are completely dependent on others for their well-being and protection. Second, setbacks to well- being in childhood can have negative effects that are often irreversible and lifelong.”

The paper goes on the explore the many impacts and issues associated with the decisions that go into reopening schools, framed around four main moral values: well-being, liberty, justice, and legitimacy.

And more

This week, we hope to give you some insight into the decisions being made and their impact on your children, students, and significant others.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to play out and the landscape continues to change, the factors will increase, change, and shift in unpredictable ways.

Stay tuned.

Recommended reading