About this parent’s guide: The term “learning differences” covers a wide range of challenges students may face in school, at home, and in their community. It includes all children who are struggling in school because their brains are wired uniquely — whether a learning disability has been formally identified or not. This parent’s guide can be helpful for all parents of students with learning differences. However, it is designed to be particularly helpful for those with children who have, or might have, a specific learning difference or other health impairment (e.g., attention issue) as defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

This is Part 2 of a series of parents’ guides related to learning differences. Click here to read Part 1.

It can be hard to acknowledge that your child has difficulty in school, let alone a potential learning disability. Perhaps you worry that putting them in a special education classroom away from their peers will call attention to learning problems. Maybe you fear that your child might be labeled as “slow” or a “behavioral problem,” or even sent to the wrong class.

As a result, many parents may avoid getting their child evaluated and starting the process for getting much-needed help. Other times, parents advocate vigorously but run into road blocks at the school or district level.

But it’s important to remember that learning differences are not defects, and access to instruction that meets students where they are is actually the law. Moreover, the state is required to supervise schools’ compliance with these laws, a responsibility which North Carolina designates to the Department of Public Instruction’s Exceptional Children Division.

Laws like the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (504) say these students must be given free appropriate public education with the least disruption to their classroom experience as possible. And DPI’s own guidance says “students with disabilities are always general education students.”

This guide will walk you, step-by-step, through the process of getting your child the help they may need to succeed and thrive — while ensuring they don’t get left behind or disadvantaged along the way.

IDEA vs. 504

Students can get accommodations and modifications to their instruction under either IDEA or Section 504. Either way, the goal is to give the child the resources they need for a free appropriate public education (as stated in Section 504) in the least restrictive environment possible (as stated in IDEA).

“Special education is not a place,” said Virginia Fogg, attorney at Disability Rights North Carolina (DRNC). “Your child does not have to leave their regular education classroom to get special education. In fact, basically, IDEA says you should get special education in the regular education classroom if it’s at all possible to do it that way.”

That could mean a special education teacher meeting with a general education teacher to explain how to modify work.

That counts as special education.

Another option is what’s called “push in,” where a special education teacher comes into the classroom and spends time with a student. They may participate in explaining the lesson or visit with the student at their desk while they’re doing independent work.

That also counts as special education.

“Those are ways that it becomes a little less obvious to anyone else around that the child has an issue,” Fogg says. “And maybe less obvious to the child, too.”

Getting evaluated and forming a plan with experts is critical to that goal. As is choosing the right law to pursue rights under. The primary differences between the two are that IDEA is more structured and offers more parents’ rights — but it also requires that a child need “specialized instruction” for eligibility.

“Under IDEA, it’s a much more formal process,” Fogg said. “Parents have more bright line participation right in the meetings and in making decisions, and there are some appeal rights that you have under IDEA that are, I would say, better than 504, for the most part.”

If a child is already getting accommodations or modifications that are working, it may make sense to proceed directly through 504 and work with the school on formalizing a plan (more on this below). If not, however, Fogg suggests starting the process more broadly — by getting an evaluation that would determine eligibility under IDEA.

Then, if the student is not eligible for specialized instruction, “literally in the same meeting, on the same day, around the same table, you can write a 504 plan because the evaluation’s already done. That, to me would be the most seamless process,” said Fogg.

But, if the student is determined eligible for specialized instruction, the IDEA process can continue.

Seeking help under IDEA

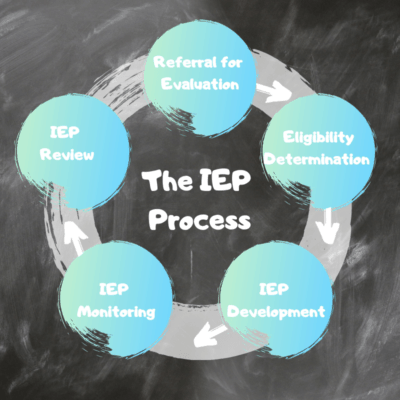

Under IDEA, the process is essentially:

- the child is referred for evaluation,

- within 90 days from referral, an eligibility determination is made,

- if eligibility is determined, an IEP is developed for the child,

- services are delivered and progress is tracked,

- the IEP is reviewed annually for as long as services are needed.

1. Referral for evaluation

When a school makes the determination that an evaluation is needed, they will contact the parent. But what if the parent is the one who has persisting concerns and wants to make the evaluation? What if the parent has worked with the school on other interventions, such as through multi-tired systems of support (MTSS), and it doesn’t seem to be working?

Under the law, a parent has the right to request the evaluation and have the school perform it at no cost to the family. This request must be in writing and, if a parent needs help putting the request in writing, they can tell the school that and verbally make the request — at which point the school has an obligation to put it in writing.

The written request must include a brief statement as to why the parent believes the evaluation is warranted.

“It can be like two sentences or one sentence,” Fogg said. “It can be, ‘My child is not reading on grade level and is falling further behind,’ or, you know, ‘My child has not been able to learn multiplication tables even with repeated instruction and practice.’ That can be the whole thing. Or you can just say, my child is getting all 1’s on their report card.”

DRNC has a sample letter on their website, available here.

Fogg’s advice when a parent sends a written referral to the school is to copy the principal and also the school district’s exceptional child (EC) director. A list of EC directors can be found here.

She gives this advice for three reasons:

First, it can expedite the process, which is critical. Under law, the school has 90 calendar days to make a determination of eligibility.

“But, I mean, 90 days is half the school year,” she said. “And if you are struggling, and you take 90 days to even get an evaluation, it’s going to be the second half of the school year before you start getting what you need, assuming you started in the very beginning of the year.”

Second, the EC director can provide oversight to make sure the referral is followed through.

“Sometimes, parents put it in writing in an email to the teacher and the teacher then didn’t refer it to the EC department,” Fogg said. “We definitely see instances where we feel like the regular education teacher is telling us that they are pressured to not make referrals. Because it costs the school more money often when the students actually get an IEP, and they have more affirmative obligations to do certain things and they can get in trouble if they don’t do those certain things.”

Schools do get federal funding, but IDEA has never been fully funded at a federal level. In fact, as we’ll explore in Part Three of these parent’s guides, the state caps funding at 12.75% of a district’s total students, even though, on average, district’s have about 13.5% of their students classified as “exceptional children.”

Third, EC directors have more formal training in special education services.

“Some principals don’t have very much training in special education,” Fogg said. “And that’s just a product of what they’re required to know in order to become a principal to get their certification. It would be helpful if they knew more and had more formal training. But if you can get yourself into the EC department, a lot of times that is what makes the wheels start turning.”

2. Eligibility determination

Within that 90-day period following a referral, the school will call an eligibility determination meeting. If your child is deemed not eligible under IDEA, parents have appeal rights — the easiest of which, Fogg says, is the state complaint (also called a formal complaint). The state complaint is available in both English and Spanish.

The Exceptional Children’s division of the Department of Public Instruction offers some guidance on filing a state complaint. The complaint is filed with the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) and referred to a dispute resolution consultant who will call both the parent and the school. DPI has 60 days to resolve the complaint and issue a written decision.

If DPI orders corrective action, it often means a re-evaluation or instruction to use a different evaluation to consider a different area of eligibility.

“Because some areas of eligibility can be quite broad, you might not qualify as having a specific learning disability in, say, reading,” Fogg said. “But that doesn’t mean that you might not qualify under another category called ‘other health impairment.’ That deals with your ability to sustain attention and to keep working for certain period of time. Or even if you don’t have a specific learning disability in reading — if reading is just more difficult for you — you might qualify under that.”

Another appeal process can occur through a petition for due process, but that is a more formal and cumbersome process where parents might want to consider hiring an attorney.

3. IEP developed for child

Often times, if your child is determined eligible under IDEA, the next step is to start formalizing an Individualized Education Program (IEP) plan. This can happen, or at least begin, at the eligibility determination meeting. Regardless, it often occurs within the same 90-day period following the referral.

The IEP planning process is conducted by a team which will include the psychologist and special education instructor from the school. But parents should know — and remember — that they are part of the IEP team also.

The team will look at the child’s current levels of educational performance using checklists that span a multitude of areas. Then, the team will write goals for where the child should be within the next calendar year.

It is helpful for parents to bring examples of their child’s work, as well as any data reporting you have received on your child — which can come from whatever screening tools the school uses (one source of data for the universal screening system is data derived from the General Assembly’s Read to Achieve Program — which mandates early literacy screening for K-3 students. Think: mClass, Star Reading, iReady — or, as may soon be the case statewide, IStation).

“Really, IEP goals should be based on data and not on some general anecdotal information from one teacher in one subject,” Fogg said. “IEP goals are supposed to be measurable and measured. So you should be able to look at the goal and tell exactly what that child should be able to do when they are meeting that goal.”

Coming up with measured and measurable goals is imperative, says Fogg, who recommends parents utilize resources, such as those available at Wrightslaw, for guidance on writing effective IEP goals.

“So for instance, sometimes it will say the student will read a text and answer comprehension questions correctly in three out of five tries. Well, my problem with that goal is I don’t know what level of text you’re expecting that child to read. And the level of text makes a big difference in whether they are able to meet the goal, and whether they’re keeping up with your class. So I would want it to say that student will be able to read a second grade level text and answer comprehension questions.”

There are resources online — such as at Understood.org — for writing effective (and measurable) IEP goals. And if you’re this far into the process, it may be worth investing in Wrightslaw’s “All About IEPs” book, which has a whole chapter on writing effective IEP goals.

“Parents should be able to know — what is the specially-designed instruction that’s going to be provided my child? What is instruction that is going to accelerate the progress?” said Lynne Loeser, statewide consultant to the Exceptional Child Division of the Department of Public Instruction. “Schools should be able to describe, ‘This is what we are going to do — the frequency, the amount of time, who is going to deliver it, how are we going to instruct your child in these areas that have been identified as areas of need? And I’ll be real honest with you that we’re not doing this all. But we should be able to describe this instruction.”

If parents are not satisfied or feel like they are not being heard in IEP meetings, a parent can contact DPI and ask for an IEP facilitator.

“Especially if parents are in a situation where they feel like they’re not being heard,” Loeser said. “Sometimes IEP meetings don’t allow for the parent’s information and experiences to be taken into account in the way that IDEA requires in those situations. If you have administrators who are really not used to listening to parents, or a parent who maybe isn’t really sure of how to communicate the information that they know, facilitators can really help with that.”

4. Monitoring the plan

One important step in monitoring your child’s progress is making sure that you receive the quarterly report that is mandated under IDEA.

“Here’s the real kicker — almost nobody does the progress reports,” Fogg said. “And it’s really sad. And we’re really hoping that that will change once DPI starts using ECATS, which should happen in August.”

ECATS, which stands for Every Child Assessment and Tracking System, is a software tool that DPI has been rolling out. In addition to other data, it will monitor IEP performance, deadlines, and violations.

Fogg suggests that parents remember to look for progress reports every time their child brings home a report card. And if they do not receive one, “you’re going to have to email the principal or the EC director and special education teacher and call them on it.”

The progress report should state each IEP goal and whether they are making adequate progress to reach the goal by the annual review.

ECATS, says Loeser, should help elevate the quality of progress reports given its ability to track data.

“Traditionally, even when you get one, the quarterly progress report is not very quantitative, it’s qualitative,” she said. “Like, your child is making great progress. Period. With ECATS … the goal is that we will be able to provide that kind of quantitative data.”

5. Reviewing IEP goals

On the 364th day following creation of an IEP plan, the IEP team is required to meet and review a student’s progress against the plan’s goals.

However, Fogg wants every parent to know that you do not have to wait until the annual review. A parent can call an IEP team meeting at any time.

“You could meet six times in a year,” she said. “And the school can call IEP meetings if they feel like there’s a problem. Particularly with behavioral problems, they’ll call an IEP meeting. But parents can request, in writing, and then the school has to respond within a reasonable period of time. They have to have the IEP meeting at a time when the parents can attend, and if the parent has a very strict work schedule, they can participate by phone. But that’s something I think is not always clear to parents: That you’re not just limited to that annual review.”

504 modifications and accommodations

Under 504, the process is less formal but offers fewer rights to parents. In fact, under 504, schools are not even required to invite parents into the meetings — though they often do.

Typically, under 504, schools are looking at what accommodations and modifications a student might benefit from.

Accommodations address how a student learns the material, while a modification changes what a student is taught or expected to learn. For instance, for classroom instruction, an accommodation for a student with dyslexia might be listening to an audio version of a book, and for a student with attention issues, it might be sitting next to the teacher. But these students would still be using the same book and doing the same work as the rest of the class.

A modification might be assigning a student shorter or easier reading assignments, or homework that is different from the rest of the class. Understood.org has a list of common accommodations and modifications available here.