|

|

North Carolina’s system for rating child care quality is under revision as child care programs face a financial cliff this summer.

It will be even harder for parents to find and afford child care, and for programs to offer competitive wages to their teachers, when federal stabilization funds run out at the end of June, experts say.

Meanwhile, leaders are rethinking the system originally designed to give parents information on the quality of child care programs — and to improve their quality.

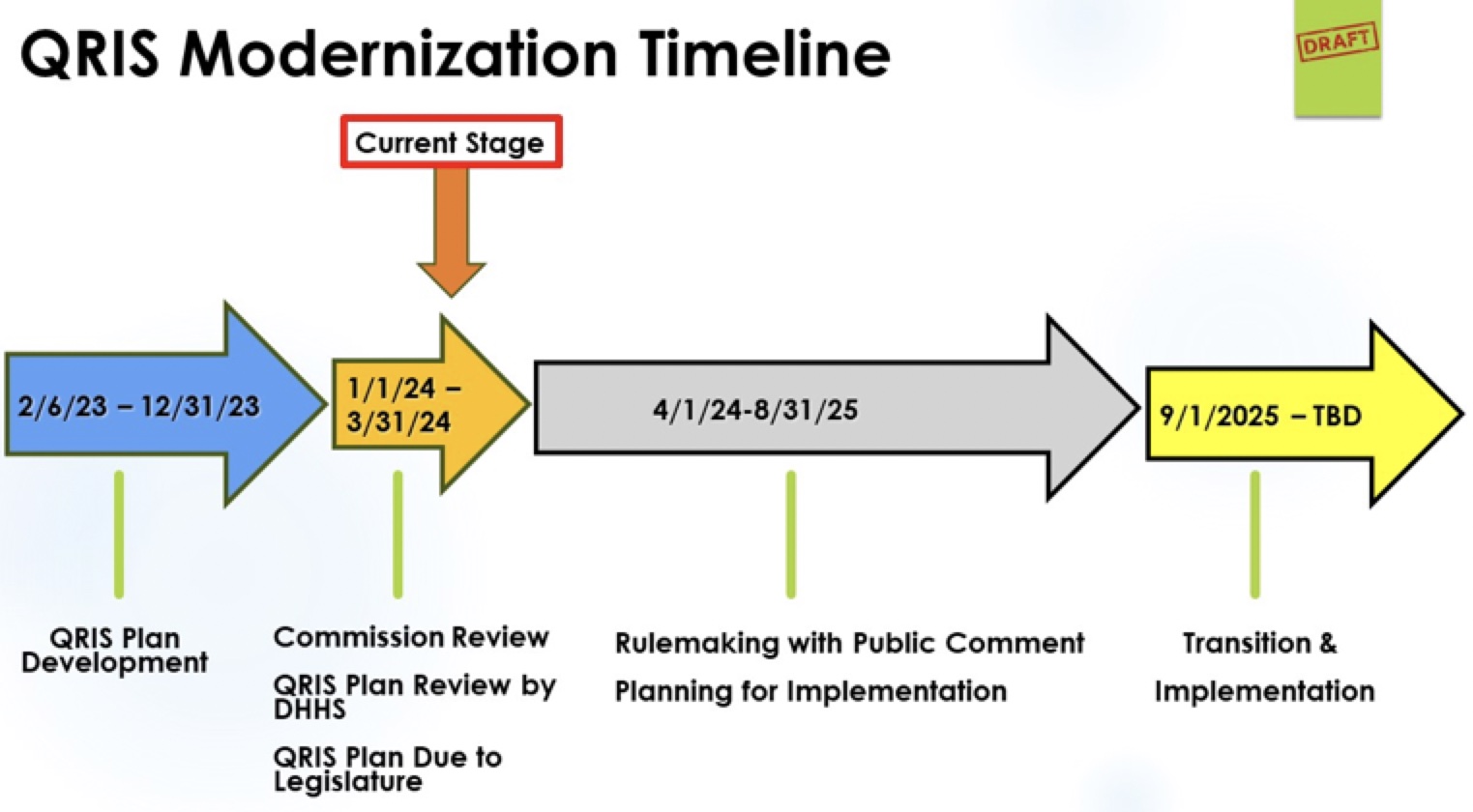

The Child Care Commission sent a report Monday to the legislature in response to a law passed last year to reform the state’s Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS). The law was proposed after some providers said they were having trouble meeting standards in a post-pandemic reality. Finding teachers with appropriate education levels without a way to compensate those teachers accordingly has been especially difficult, owners and directors say.

The framework in the commission’s report will give more options and flexibility to child care programs. It infuses new measures of quality, such as updated assessments that focus on teacher-child interactions and family engagement standards. And it will acknowledge teachers’ experience and other credentials instead of focusing on their formal degrees.

“I do think we can see it as an opportunity to just improve on a system that’s 18 years old,” said Iheoma Iruka, a commissioner and research fellow at the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute. “We’re trying to both meet the context that we’re in following the pandemic, but also … hopefully we know a little bit more than we did two decades ago.”

The report’s framework is just the beginning. The commission has its own rule-making process that will hash out the details of the updated QRIS. Actual changes in requirements will not start until late 2025, at the earliest. There will be more opportunities for public input during the rule-making process.

Instead of the current single option for demonstrating quality, the new framework includes three options that licensed centers and family child care homes can choose: program assessment, classroom and instructional quality, and accreditation and Head Start.

“This approach is really trying to give providers some more flexibility and opportunity to shine for that which they are confident and good at,” said commissioner Susan Butler-Staub.

Changing standards will not fix the underlying issues of child care access, affordability, and low teacher wages, Butler-Staub said.

“QRIS does not and cannot address all of the issues of the system,” she said.

Advocates last year requested $300 million from the legislature to help programs avoid this summer’s child care cliff. Legislators did not allocate those funds.

“This bill was proposed right next to a huge funding bill that did not get passed, so I think it’s important to recognize that,” she said.

What’s new?

The new framework gives different options for licensed programs to be rated one to five stars. The first avenue, program assessment, is most similar to the current system. An outside consultant will observe the program and rate it using an updated version of the Environmental Rating Scale that focuses more on interactions.

Interactions were “identified across the state as the highest indicator of quality,” said Kimberly Mallady, QRIS project manager at the Division of Child Development and Early Education, referencing community listening sessions the division conducted last year to hear feedback on QRIS.

The second pathway emphasizes curriculum and instruction. It rewards smaller teacher-to-child ratios, the implementation of a state-approved curriculum, the use of formative assessments to inform instruction, and coaching and training to improve instruction.

The third pathway recognizes accreditations by national bodies and Head Start.

The first two pathways build in components previously unrecognized by QRIS, such as continuous quality improvement, rewarding programs and educators consistently sticking to plans to meet specific goals rather than being rated once every three years.

The new QRIS also will set standards for family and community engagement. Higher star levels will reward programs that go above and beyond basic communication, building in meaningful engagement, leadership, and educational opportunities and events for families and community members.

Shifting education standards

The new pathways reward formal degrees and credentials less than the current system. The new pathways require 50% of lead teachers, as well as 50% of other educators in a program, to meet certain requirements for each star level.

The current QRIS requires 75% of lead teachers to have a degree and two years of experience, with an additional quality point available if all lead teachers, and 75% of teachers, have degrees. Programs have been operating with a pandemic exception in these standards.

Though the new scale’s specific requirements will be decided in the rule-making process, the approved report says the new system will recognize experience, the national Child Development Associate (CDA) credential, continuing education units, competencies, and course completion without degree completion.

Loosening formal degree requirements might make it easier for providers to keep their doors open, said Sherry Melton, policy consultant and lobbyist for the NC Licensed Child Care Association.

“The framework that they approved has the potential to, first of all, expand access to families, to help providers open up classrooms that they aren’t able to have open now, and allow families desperate for care to get their children into care and off of waiting lists, because it expands the talent pool that’s available,” Melton said.

‘A Band-Aid’

Some leaders are concerned that less formal education requirements could lower the quality of care. Research is indecisive on whether degrees raise student outcomes in early childhood settings.

J. Lanier DeGrella, a commissioner and retired early childhood professional, was the only commissioner to vote against the report Monday. She said she values teachers’ experience, but is worried that too much loosening of formal education requirements will hurt classroom quality.

“It feels like a Band-Aid for our current crisis,” DeGrella said. “… Sometimes, the longer the Band-Aid’s on, the harder it is to take it off.”

Cyndie Osborne, president of the NC ACCESS early childhood faculty association, said that loosening education requirements could have consequences beyond classrooms.

“We are plugging the pipeline and keeping teachers from upward mobility,” Osborne said. “Who is going to replace those who will be retiring in higher positions in the field of early childhood, when education is not encouraged in the child care setting, since it is just one part of our field?”

Though the role of formal degrees in QRIS is a point of contention, all educators, advocates, and commissioners point to a need for funding to support the early childhood workforce.

“If there’s not compensation, we will not be able to recruit, we will not be able to retain educators,” said Rhonda Rivers, vice chair of the commission and regional director of education for LeafSpring Schools.

“At the end of the day, we need investments,” Rivers said. “We need for our legislators, our elected officials, to understand the value of these investments.”