|

|

Behind the Story

This is the fourth piece from “School’s not out,” a series of stories from the road this summer about child care providers and the communities that rely on them in every season. In the absence of national and state investments, local leaders are stepping up to work toward solutions to the child care crisis. Meanwhile, federal relief funds are running out at the end of this year, leaving many programs with tough decisions and families with even fewer affordable child care options. Subscribe to Early Bird to follow along as EdNC documents this particularly fragile moment in early care and education. Go here for past stories in the series.

Most of the people touring Care-O-World Learning Center in Ayden, the newest branch of the regional nonprofit chain in eastern North Carolina, did not have young children.

They were not stuck in the difficult hunt for a spot in a facility that works for their child, their family’s schedule, their address, and — most of all — their budget.

Instead, they were local business owners, politicians, and community leaders. They were folks like Cindy Goff, a commissioner for the town of Ayden finishing her first term and up for re-election soon, who received an invitation to the event that Tuesday. Goff has been hearing from parents and employers alike that the lack of child care is a rising concern, she said. So she came to check out the program, which will serve 222 children, from infants to school-age children, before and after school.

“Business owners will say, ‘I can’t find help,'” Goff said. “For a lot of families, just the cost of child care eats up their salary. So it’s like, I’ll just go ahead and stay home.”

Goff had heard about these struggles, she said, but the lack of sufficient child care is not a topic of conversation among the town’s commissioners. She said more community awareness — and more collaboration between the business community and elected officials — is needed.

That was the point of the event, said Sara Cariaso, Care-O-World’s director of operations: to get a broader audience engaged in the importance of child care and willing to work toward solutions.

“It’s not just something that only affects parents or grandparents or caregivers,” Cariaso said. “This is a community matter. It takes a village, and to be part of that village, it takes everyone being informed. It takes everyone to advocate for these things.”

‘We try to treat people good’

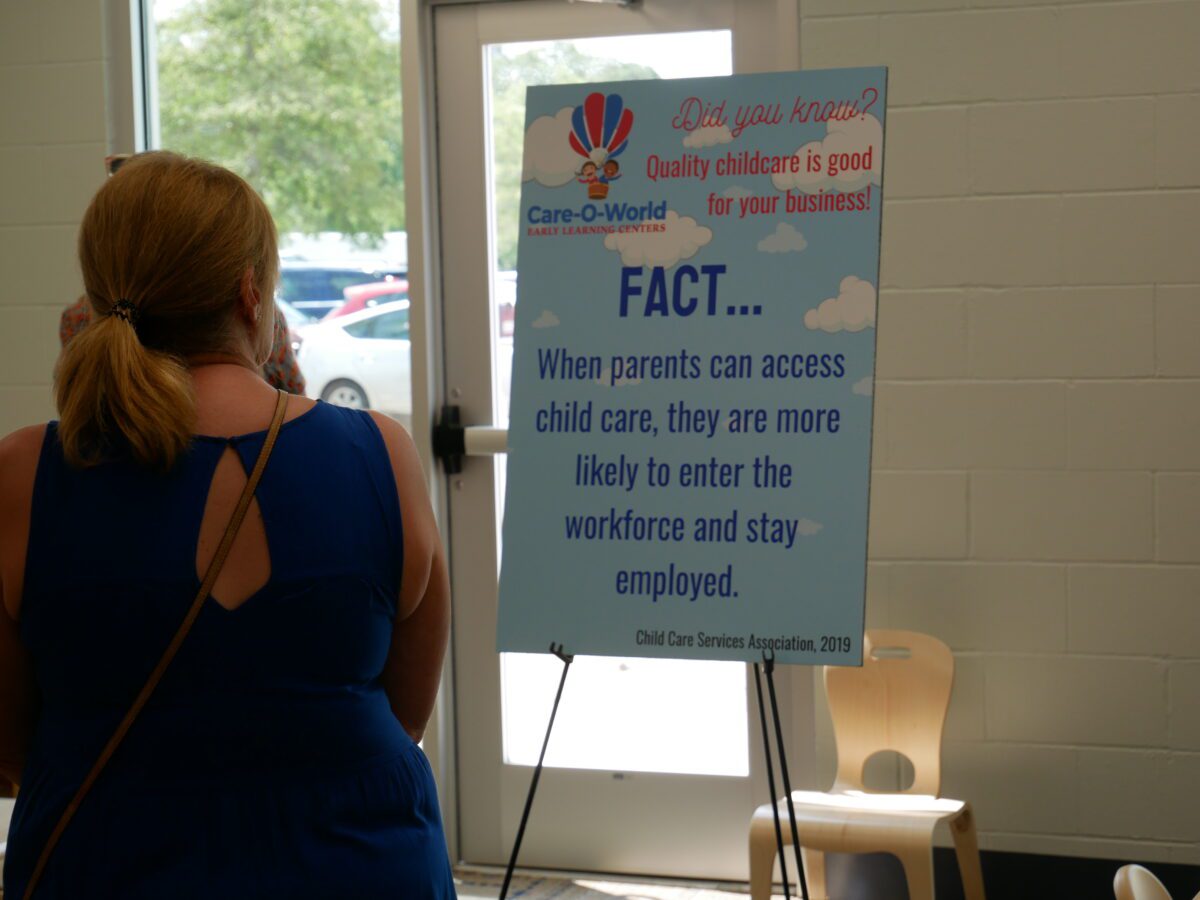

As groups made their way from the lobby to classrooms, outfitted for specific ages, Care-O-World staff shared the history of the facility and the plans for the program. They also pointed to large signs in each room that talked about the importance of child care to everyone: the economic and societal gains on child care investments, and the losses without those investments.

“If it’s not something you kind of live in or do on a day-to-day basis, it’s kind of an ‘aha,'” Cariaso said. “It’s a shift for you to think of it that way.”

Care-O-World started in the home of Carolyn Carrow. The first site opened in 1987, and the fourth will open this month. Jason Carrow, Carolyn’s son, is the executive director.

After acquiring a background in engineering, Jason said, he quickly learned he wanted to do something different. He cares, he said, about quality: of teachers, of materials, of food, of culture.

Two of Care-O-World’s open locations, in Washington and Chocowinity, have five out of five stars on the state’s rating scale for licensed child care programs. The third, which opened during the pandemic in Winterville, has four.

When EdNC attended the open house, Jason said he was actually eager for the state to return to its stricter pre-pandemic quality requirements.

“We’re going to have six classrooms to begin with, and all of them are going to meet that high standard for a teacher,” he said.

He provides benefits, including child care discounts for the employees’ own children, and partners with the TEACH program for teachers to further their education for free.

“We try to treat people good,” Jason said. “And even if somebody treats you bad, you still treat them good. That’s just the kind thing to do.”

Cierra Askew, director of the Winterville location, attested to that.

“I have had more things done for me in like these two years than I did for the previous 10,” Askew said. “It makes me feel appreciated.”

She’s been to two professional development conferences in Nashville, Tennessee, and in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She’s been on a cruise with the organization. One day, she said, Jason called her and asked how many people were there that day.

“I told him, and then he dropped $50 off for everybody that was here,” she said.

‘Whoever walks through our door, we’re happy to have’

In the entry hallway of the new facility in Ayden, the program’s core values are framed: kind, smart, and playful.

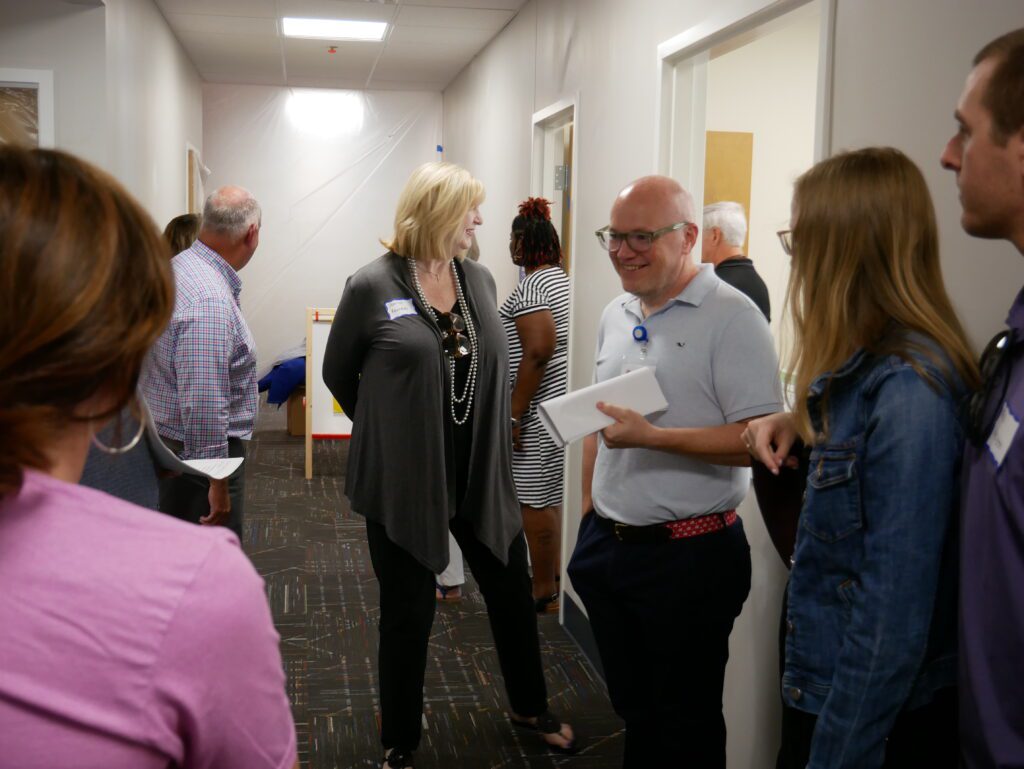

“If we can’t say that it’s kind, smart, and playful, we’re probably not interested,” Jason said as he conducted a tour for a guest whom the staff was particularly thankful showed up: Sen. Kandie Smith, a Democrat who serves Pitt and Edgecombe counties.

The program accepts multiple funding streams at their locations to make quality care accessible to as many children as possible, including subsidy vouchers to help low-income parents afford care. As a nonprofit, the program’s mission is to expand to communities that need care, Jason said, and to meet the needs of families from all backgrounds.

“That’s one thing we are good at, and we really enjoy, is serving the whole community,” he said. “So whoever walks through our door, we’re happy to have.”

Jason Carrow and Sara Cariaso, Care-O-World director of operations, speak with Sen. Kandie Smith.

That’s not always the case, he said, in Pitt County and elsewhere. Since there is such a lack of child care, programs do not have an incentive to provide affordable care or accept subsidy vouchers, he said.

“It creates the haves and the have-nots,” he said.

Jason is an expert in the finances of child care, a business where the margins are razor thin. He is always looking for creative solutions. At one site, he hires adults from a developmental program who help wash dishes.

“They’re super happy to come in and help us clean,” he said. “It makes it more affordable for us. They’re very reliable and dependable, but it means we don’t have to purchase paper products.”

Most of the centers’ meals are not processed. “It’s healthier, but it’s also cheaper,” he said.

His largest expense, staffing, is always matched with enrollment.

“One staff member, at the end of the month, can make the difference between profit and loss,” he said.

Still looking for the most important solution

The program has been able to retain employees, despite intensified staffing shortages, and to open a new facility, while many providers consider closing. But Jason does not have a creative solution for one thing — the halt of federal relief funds at the end of this year. The organization receives about $132,000 each quarter in stabilization grants.

“That’s going to completely go away unless the state steps in and provides at least some of that money,” Jason told Smith while they stood in the new center’s kitchen.

“Our increased labor costs, almost dollar for dollar, matches what we get,” he said. “So yeah, that is super scary. How do we as an organization cover half a million dollars a year?”

He said the organization used the relief funds to raise teacher wages an average of $4 an hour.

“We’re lucky, because we’re a little bit more flexible than other people, but even for us, it’s going to be a struggle.”

That’s where Cariaso comes in. She said Jason hired her to get the word out about the critical need for change. By acting as a “community convener,” she said she wants the organization to start conversations, and “to be at a table with business leaders and commissioners and say, ‘This is what child care looks like, and we’re inviting you to be a part of growing this community, growing the economy, from the ground up.'”

Looking forward, public investment is needed, Jason said.

“Whether we’re talking about Pitt County, North Carolina, or the United States of America, if they truly wanted quality child care, at the end of the day, people can add and subtract, and they could see pretty quick that public dollars are going to have to go to child care,” he said. “Without that, I don’t know what child care is going to do. You’re going to have the haves and the have-nots.”