|

|

As the science of reading gained attention in recent years, the narrative, sometimes oversimplified, irked some academics. Patricia Fecher counts herself among those who strained to understand the big fuss.

Fecher was a reading teacher when the National Reading Panel published its report on reading instruction more than 20 years ago. She learned the various components of reading acquisition and taught according to what her students needed. When she entered academia, she brought that approach to her future teachers.

So when North Carolina enacted its 2021 reading law grounding literacy instruction in the science of reading, and mandating that educator preparation programs (EPPs) train teachers accordingly, she initially struggled to understand the need for sweeping mandates and considerable investment in Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS).

“I spent more time trying to figure out what the hype was about science of reading,” said Fecher, who is now an associate provost and professor at Methodist University in Fayetteville. “The narrative assumes that there was no structure (in teacher preparation). There was.”

The information didn’t seem new to her. But she also remembers visiting elementary schools and seeing a disconnect between how EPPs taught and how EPP graduates taught. She saw teachers in North Carolina classrooms go page-by-page through reading programs, relying on the curriculum regardless of what each student needed.

The research isn’t new. But are colleges teaching in a way that helps graduates apply it in the elementary setting? Are new teachers blindly following curriculum, she wondered, or designing instruction that meets their students’ needs?

“Could we be more intentional? Were we speaking a different language, sometimes, than our K-5 colleagues?” Fecher said. “Yeah, I think there was some of that, and I think that’s what we’re addressing now.”

Fecher and her colleagues across educator preparation programs in the North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities (NCICU) are redesigning course syllabi and expanding opportunities for college students to practice instruction grounded in the reading research. And they’re doing it together, as a system, using grant money to pilot individual projects at each of their institutions and gathering at an annual literacy summit to share their experiences.

“The spirit of collaboration here is unreal,” said Monica Campbell, chairperson of Lenoir-Rhyne University’s school of education and co-chair of the NCICU’s literacy task force. “There’s so much excitement.”

College courses under the microscope

The state’s 2021 reading law included changes for teachers in pre-kindergarten through fifth grade, but also for EPP instructors. The state required an independent evaluation of courses at EPPs in both the NCICU and the UNC System.

The reaction to that evaluation has differed. The UNC System’s Board of Governors expressed frustration with largely underwhelming evaluations of its colleges of education. But the NCICU used them as a benchmarking tool, and offered support to each institution to address shortcomings.

TPI-US, which conducted the UNC System evaluation, also evaluated some of the NCICU programs. All of the NCICU’s 31 colleges of education also conducted a self-study across 104 competencies. NCICU then contracted with Compass Research and Evaluation for an analysis of the findings.

Literacy leaders at the colleges of education said the self-study instrument and process were more enlightening than they expected. They told the General Assembly that the study revealed unanticipated strengths and needs at a more granular level. The work has led to course redesign, as well as colleges adding new courses on literacy.

Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs is a good example.

When Diana Betts arrived at Gardner-Webb as an assistant professor of literacy and reading, she inherited three literacy courses.

“However, they were not completely aligned to science of reading,” she said.

How coursework is changing for future teachers

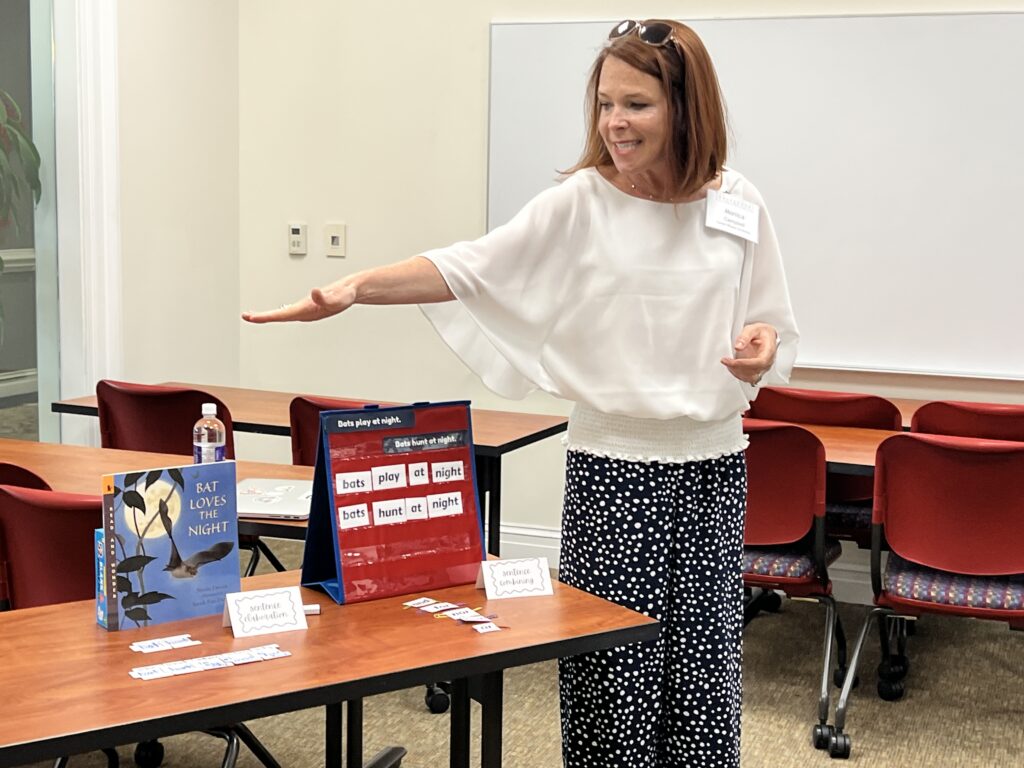

Betts reviewed the courses, took feedback from the independent evaluation, and started taking out lessons that didn’t belong. But she knew her college graduates would enter North Carolina schools expected to know the reading research and be ready for LETRS training.

So she also worked with the North Carolina School Improvement Project to get her teacher candidates Reading Research to Classroom Practice (RRtCP) training. RRtCP was the first state education agency science of reading course certified by the International Dyslexia Association.

“They will graduate with our RRtCP level one, so that is huge,” Betts said. “The way that I’ve heard RRtCP described is, if LETRS is like the bachelor’s degree, RRtCP is like the associate’s degree. It will give them a solid foundation prior to them jumping into LETRS training as a fully-licensed teacher.”

The evaluation also called out ambiguity in program syllabi and course descriptions. At Campbell University, that meant revising clinical opportunities to ensure that they weren’t just observational – meaning that teacher candidates actually get to practice the lessons they’re learning in college while working in K-5 classrooms.

Campbell’s evaluation also included feedback that it should better prepare teacher candidates to serve diverse learners. Some instructors said they addressed this in their courses already, but the university revised syllabi anyway.

“Professors move, adjuncts teach courses,” said Kathleen Castillo-Clark, elementary education coordinator and assistant professor of education at Campbell. “We want it to be documented that this is how we are being explicit about it – so, regardless of who’s teaching your courses, it gets taught.”

A time for cooperative learning

The NCICU convened a task force, in 2022, which is working on best practices for literacy instruction. To help research, develop, and implement support systems for faculty to fully align college courses with the science of reading, the Goodnight Educational Foundation provided a two-year grant to NCICU around the same time.

The Goodnight grant helps fund the NCICU’s science of reading implementation, and the NCICU subgrants about $15,000 for each college of education to pilot a project at their institution based on the self-study evaluation.

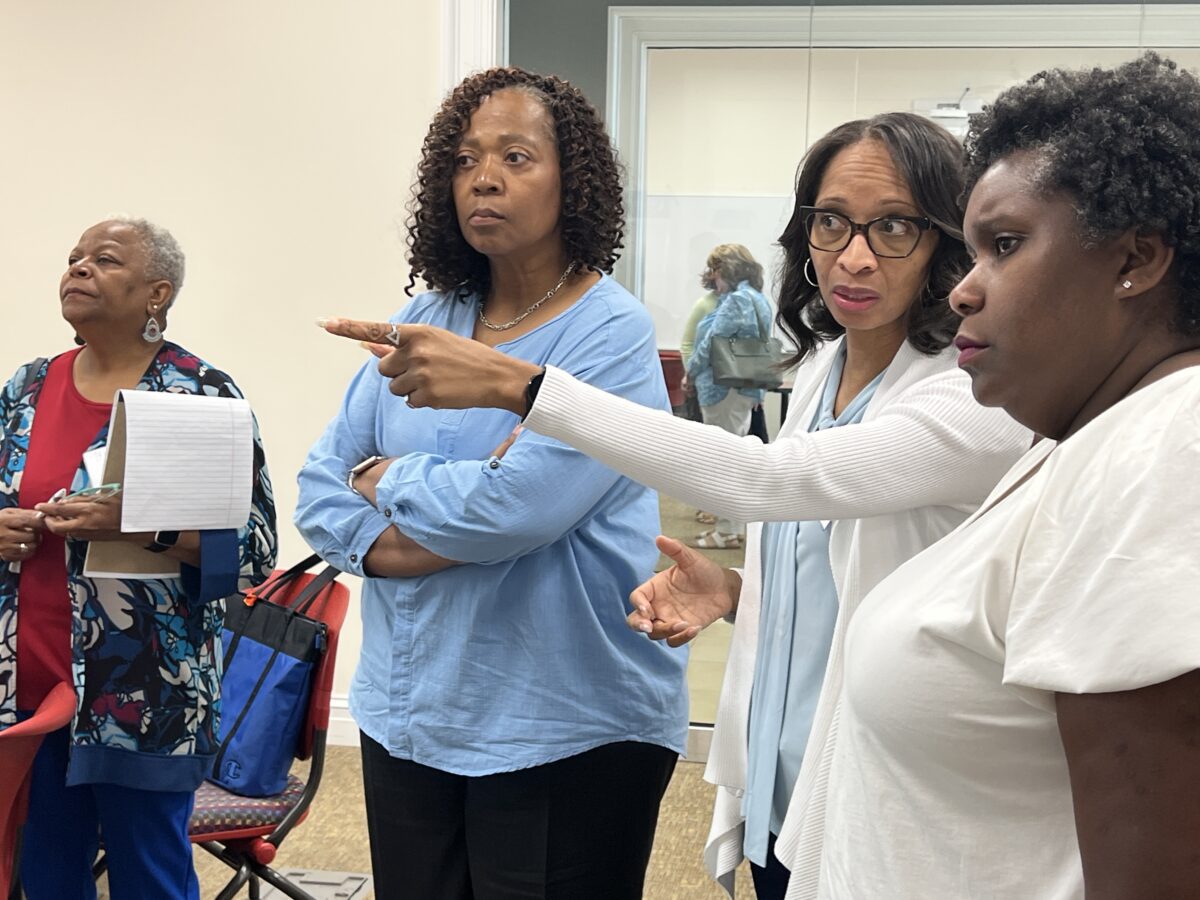

This summer, representatives from all 31 EPPs gathered at High Point University for two days of sharing challenges and victories. Above all, they share excitement as the system moves toward grounding teacher candidates in knowledge of the what and how of the science of reading.

“We recognize that reading and comprehension are keys to student achievement at all levels of education,” NCICU President Hope Williams said. “And we are so impressed with the collaboration among EPPs and the innovative ideas they have developed and implemented for the science of reading curriculum at the 31 NCICU educator prep programs.”

The summit allowed colleagues to exchange lessons being learned as they add and redesign course offerings. It also gave the institutions a chance to talk about their pilot projects.

At Duke, for example, the college of education is partnering with Hill Learning Center in Durham to give teacher candidates support to better serve students with learning differences. At Brevard, the college is piloting a community approach working with the local Augustine Literacy Project, Transylvania County Schools, and Evergreen Community Charter School.

“We’re going to have 31 case studies,” said Patsy Pierce, co-manager of the science of reading project for the NCICU. “And we’re thinking these might be interesting or helpful to other EPPs.”

Avoiding argument, fostering conversation

At Methodist, the pilot case study will include work on preparing future teachers to deliver research-based reading instruction both in-person and through web-based tutoring experiences.

It’s an experiment, in part, inspired by watching elementary teachers and students navigate the early days of COVID. And it’s an example of what Fecher likes best about the direction of literacy instruction in North Carolina: it includes institutions of higher education in the process of helping elementary schools.

“I do think that’s been the biggest shift I’ve seen here – that we are part of this conversation around elementary reading,” she said.

Fecher wants more nuance in conversations around the science of reading and what that really means. But she’s glad the conversations are happening. And she says she’s optimistic, given the nature of the conversations – particularly those between colleges of education and elementary schools.

“If you want changes in education, that’s got to go K-16,” she said. “You can’t say we’re not preparing them correctly, and then we can’t say they don’t know what they’re doing. Out of everything, that’s where I’ve found the power lies in this science of reading (push). We’re all having conversations around the same bullet points at the same time.”