|

|

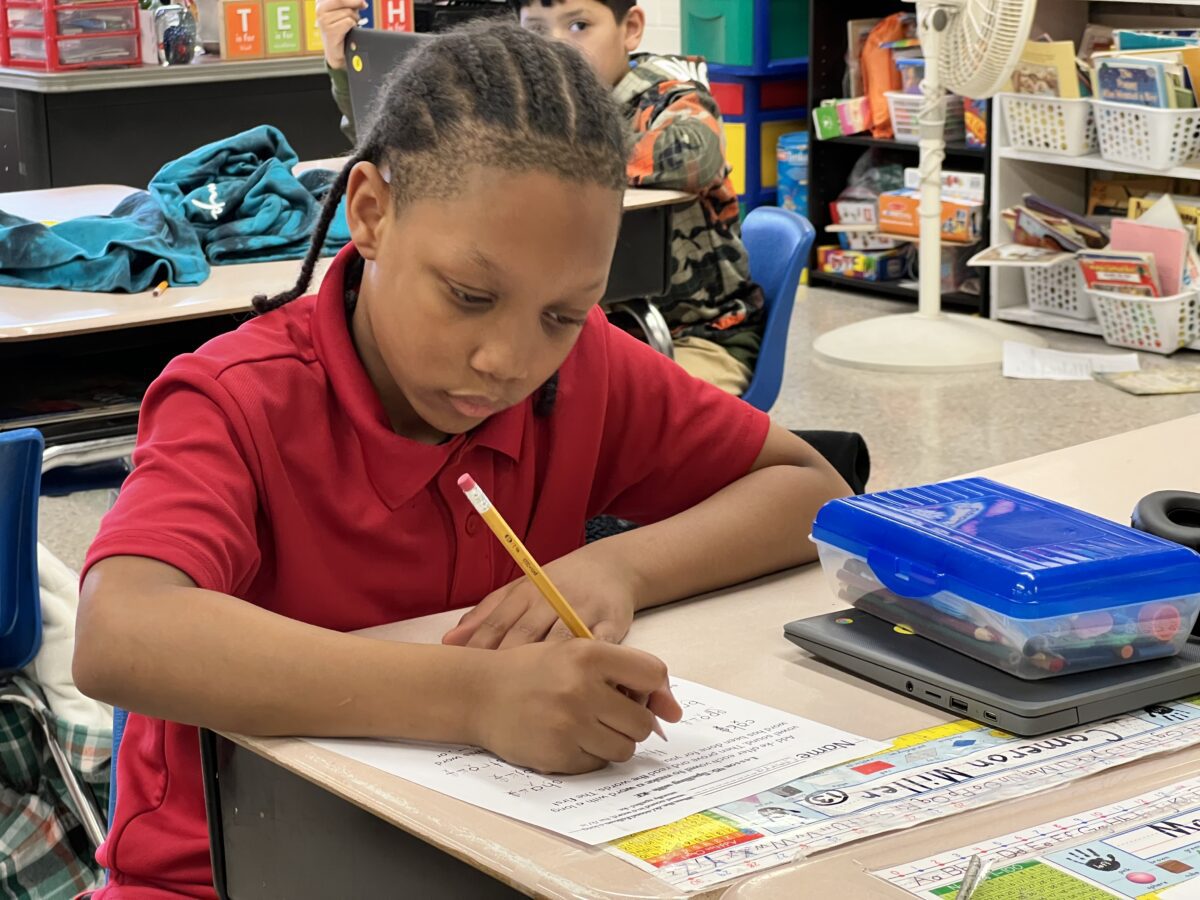

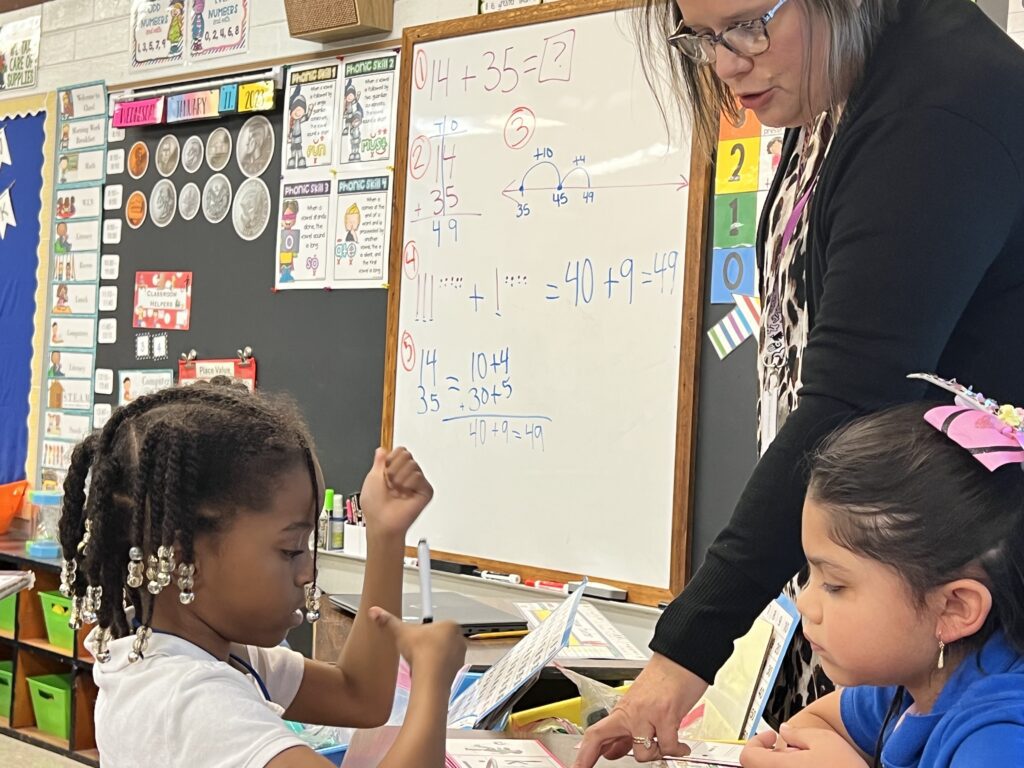

Administrators at Whiteville Primary, a school for kindergarten through second grade in Whiteville City Schools, schedule the day down to the minute. Teachers sometimes schedule their literacy blocks down to the second.

During phonics instruction, teachers might build on things their students learned while working on phonemic awareness earlier in the day. Comprehension work and read-alouds bring in vocabulary words that students worked with that day.

With the shift to instruction grounded in the science of reading, not only has instruction become more explicit — it follows a specific scope and sequence. Each lesson builds on the one before.

A student can fall behind a lot missing just one day.

That makes the state of student attendance, and on-time attendance, troubling for a state in the beginning stages of implementing the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021.

“We just have a different mentality now about the urgency of schooling,” said Pam Sutton, the instructional coach at Whiteville Primary. “We’re seeing problems with attendance. I’m not sure if it’s due to the pandemic or what, but the mentality of parents is like attendance isn’t a big deal.”

But it is a big deal, especially for children learning to read.

Behind the Story

This article is part of a series updating North Carolina’s efforts around the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021. EdNC visited 10 schools across five districts and interviewed leaders from the Department of Public Instruction, UNC System, and North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities. We wanted to learn about changes to instruction, the state of curriculum and instructional materials, the role of building student background knowledge, challenges from teacher turnover and chronic absenteeism, and where teacher prep programs are with implementation. You can find the entire series here.

This year, the State Board of Education heard data showing that chronic absenteeism, when students miss 10 or more days a year, doubled to almost 20% among elementary students in 2020-21, compared with before the pandemic. Elementary students are missing an average of 11 days of school per year.

Several studies show a negative correlation between missing school and academic outcomes. A 2018 Lexia report noted that only 17% of students who were chronically absent in kindergarten and first grade went on to read at grade level in third grade.

“We’re doing everything we can and then you have a child who’s out, so the continuity of the instruction isn’t there,” Sutton said. “If they’re not here, they miss that instruction and they miss that intervention and they miss that extra help. It all adds up.”

It’s not just days missed, either. Getting to school late – even by just a few minutes – can have a major impact on students’ ability to stay on track for grade-level proficiency, Sutton said.

Her school uses a program that adds up instructional time missed when kids come in late or leave early. That report shows how many days students are effectively missing through tardiness.

“And it’s kind of an eye opener to some parents because they didn’t think it was such a big deal,” Katie McLam said. “But everything matters.”

At Whiteville Primary, some kids had racked up 30 or more tardies just 70 days into the school year. Sutton sees them come in, sometimes just 10 minutes late. Then, they walk to their classrooms — rarely with urgency. Sometimes it takes them a few minutes to figure out what the rest of the class is doing. Other times, they go get breakfast if they haven’t had anything to eat.

“So now your 10 minutes late has turned into 30 minutes,” Sutton said. “And you haven’t started your instruction, but the class has moved on.”

Sutton says there’s a compounding effect of being late on the student’s ability to catch up — either that day or in the course of a few days.

“Some of them, it’s that anxiety of, ‘What are they doing, what am I supposed to be doing,’” she says of students’ mindsets. “And then, ‘Oh wait, my homework. Oh wait, my snack. Did I get my snack?’ There’s this whole thing happening in their minds, and it takes time to bring them down so that they can focus to learn.”

But those are precious minutes not spent on instruction. Especially, McLam said, when teachers are already pressed for instructional time.

“The day goes by so quickly when you’re trying to fit everything in that you want the students to know, and all the other things you have to do,” she said. “There’s not a lot of downtime.”

Disciplinary measures have similar effects, school leaders say. It’s important to teach students acceptable behavior, but whether the student is out of class because of absences, tardies, or disciplinary punishment — the impact on learning for the brain is the same.

At Perquimans Central, a school for pre-K through second grade, building leaders identified reading struggles as a contributor to disciplinary issues.

For years, Principal Tracy Gregory said, teachers did the best they could. But some practices they used in the past were not effective in teaching students to read. That caused anxiety and issues with self-esteem, she said, which translated to behavioral outbursts.

So they redesigned reading instruction, going all in with science-of-reading implementation. At the same time, they did all they could to avoid disciplinary measures keeping kids away.

“Kids act out because they don’t want to look dumb, even in first and second grade,” she said. “And they would be a class clown rather than being a target. But when we identify their needs, we give them the instruction they need, and they have a safe environment, you’ll see a lot of that reduced.”

And Gregory’s already seeing results. Incidence reports are down significantly, she said, this year compared to previous years.

“We are doing awesome,” she said. “I feel like this has made my job easier.”