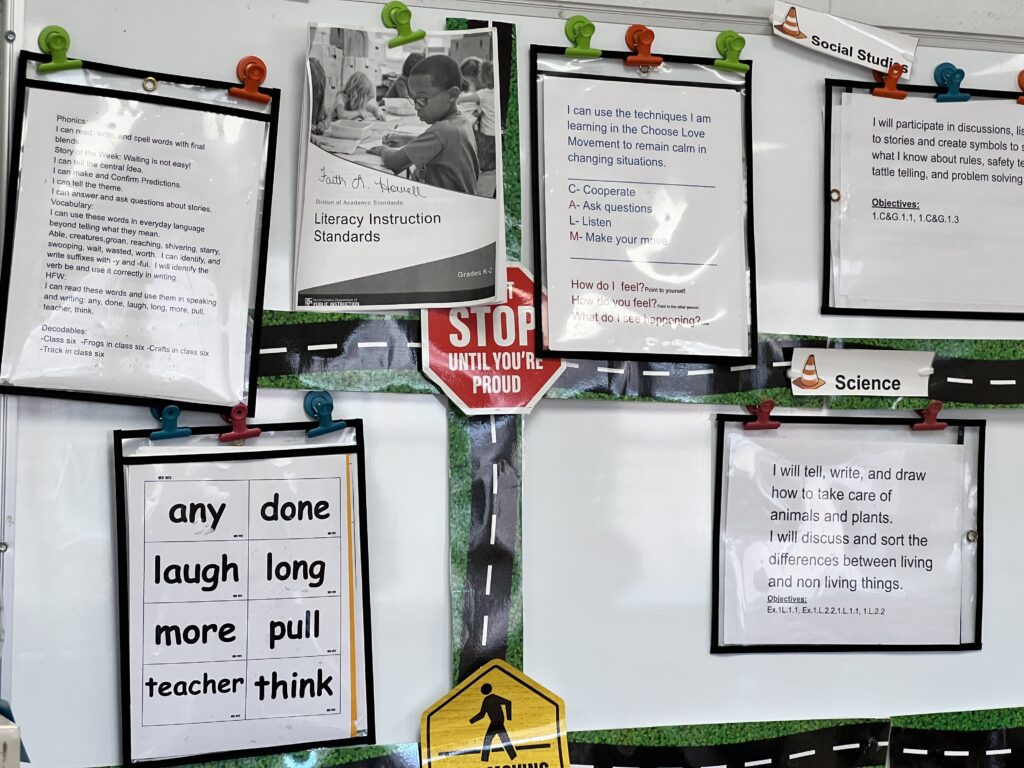

It wasn’t long after Clinton City Schools hired Theresa Melenas as its director of elementary schools that the state passed a reading law in 2021 grounding literacy instruction in the science of reading. One of her first priorities was figuring out whether the district was prepared.

The district had just bought a new core curriculum. To Melenas’ dismay, it didn’t seem to line up with the reading research. As her teachers and interventionists have gone through training using Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS), they learned how incompatible it was.

“They will tell you it’s aligned and you can find what you want there, but it is not the car I would have bought if I knew science or reading was coming,” she said.

She likes the car analogy because it helps people relate to the challenge she faces — trying to navigate improvement in reading instruction with a curriculum that’s off.

“I’m still making payments on this car,” she said, one week removed from cutting a $78,000 check to the vendor. “I can’t trade it in for a new one, so I’ve got to drive this car until the wheels fall off, and I can’t afford to buy a new one.”

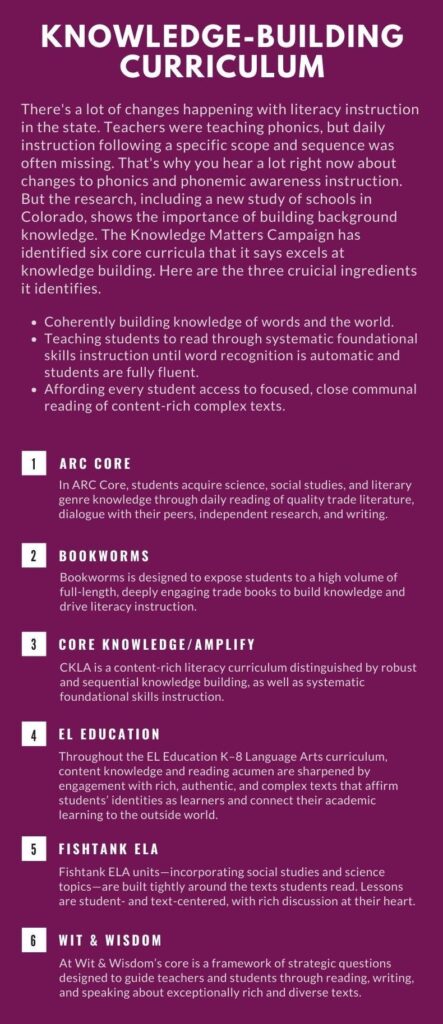

Ask anyone and they’ll tell you that the teacher is the most important factor in getting literacy instruction right. But they’ll say in the next breath that the teacher needs strong materials. For a lot of districts, those aren’t in place — and finding ways to fund and choose wisely may make all the difference.

How important is having the right instructional materials?

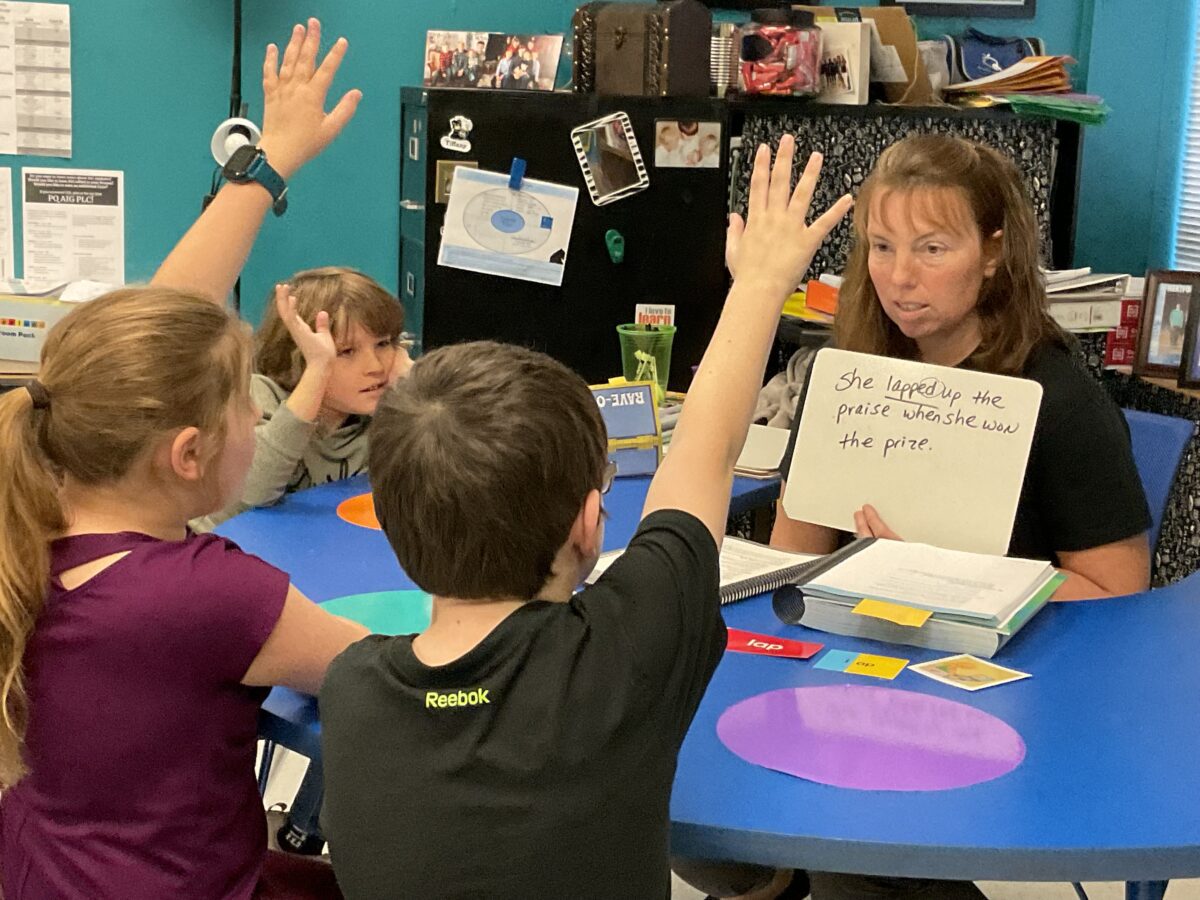

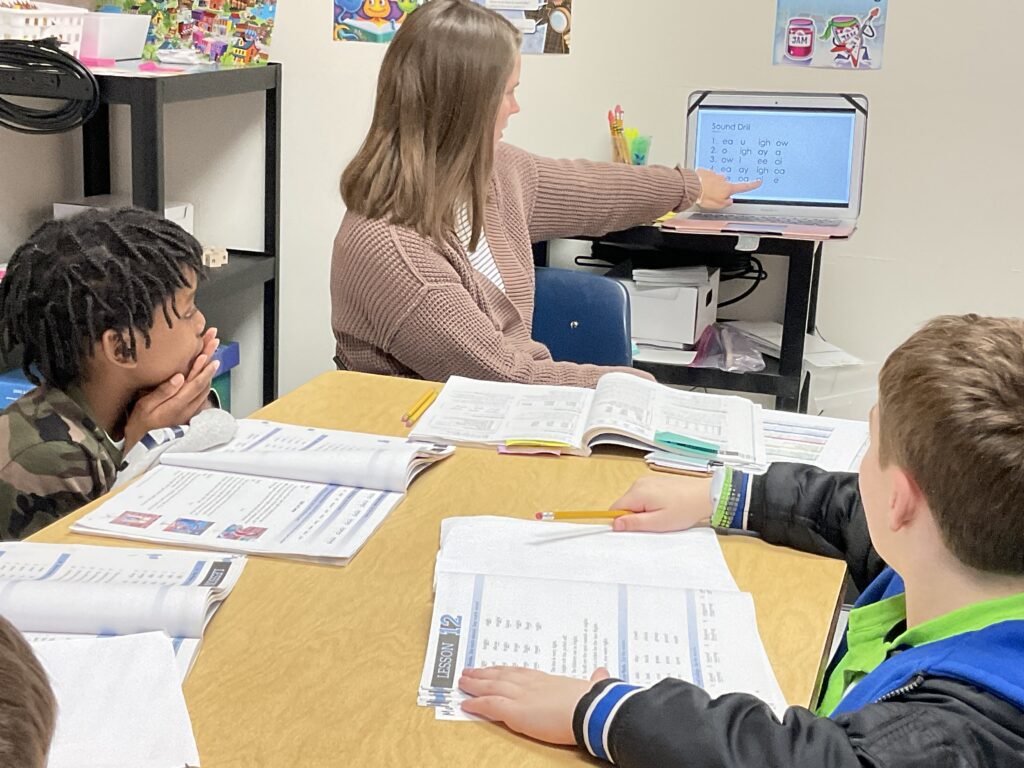

The science of reading is a vast body of research, and it includes studies of the brain, studies in linguistics, and studies of behavior. LETRS training covers a lot. That can be good, says Melissa Hedt, deputy superintendent of accountability and instruction in Asheville City Schools, because it gives teachers some background on why instructional approaches are shifting.

But it presents a challenge, too. It’s hard for teachers, with so much on their plates, to do the training, follow the evolving research, and figure out how to deliver instruction. That might help explain why, when IES studied the effects of LETRS training, it found that the training improved teacher knowledge but did not significantly move student reading outcomes.

That’s where pairing teacher knowledge with good curriculum and programs comes in, Hedt says.

“I think about the curriculum as more of the ‘what,’ and what they’re learning in LETRS is the ‘how’ – the strategies to use within the curriculum,” Hedt said. “And I think the more that our teachers are seeing the overlaps between the two, that reinforces the science of reading and the best practice that we want to see in literacy instruction.”

That overlap reinforces good practices and gives teachers confidence that the time they invest in LETRS is worth it.

“I can’t imagine, right now, if I were taking the LETRS course — I started it last year, and I didn’t have that transference between what I was studying and applying it directly to the tools that I had in the classroom,” said Sarah Cain, Asheville City Schools’ director of elementary instruction.

Piecing together a comprehensive set of instructional materials

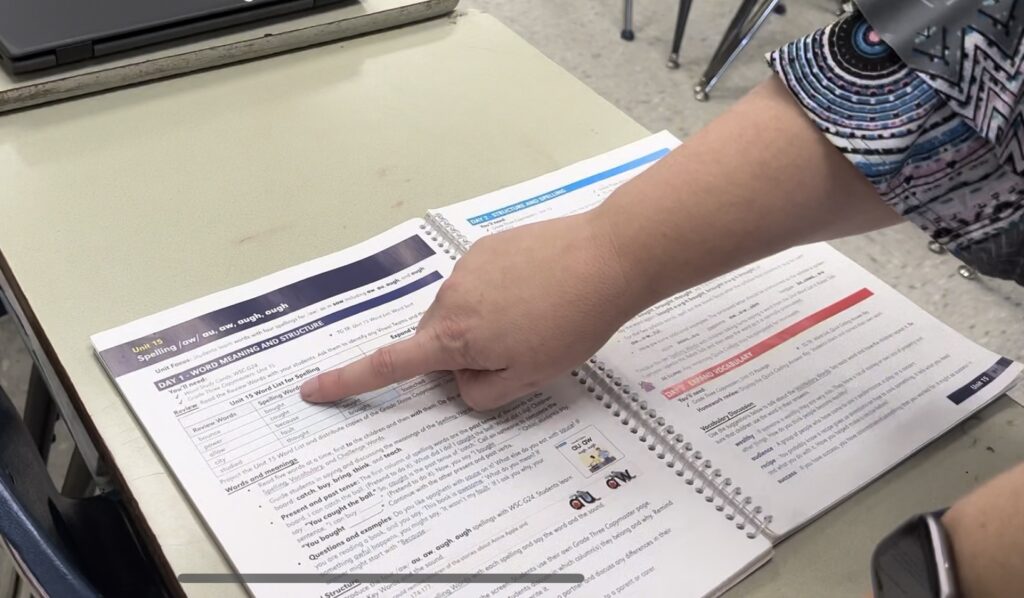

When educators talk about curriculum, often they mean more than the core program used for teaching reading.

No one curriculum does it all, they say. So they choose phonics and phonemic awareness programs to supplement a core literacy curriculum, which focuses on comprehension and, hopefully, includes a healthy dose of building background knowledge.

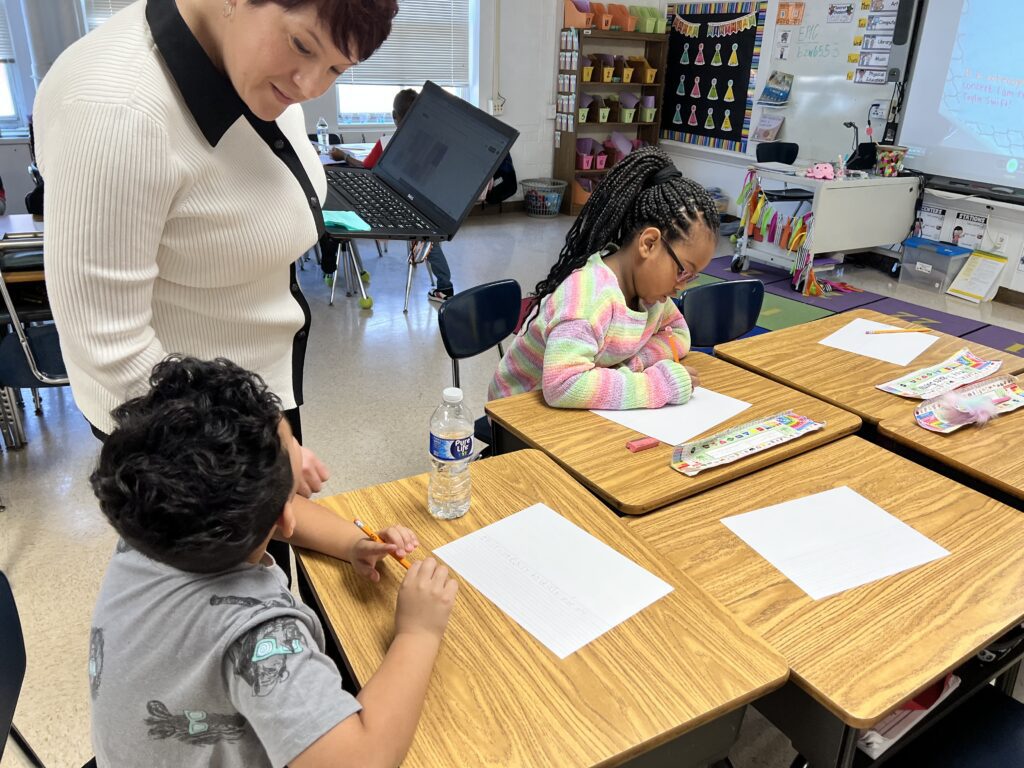

In Whiteville City, the district realized the students weren’t getting a strong foundation in phonics. The assessment data, particularly after students returned from learning at home, bore that out. So the district bought Reading Horizons for two educators to pilot— a second-grade teacher and an instructional coach.

“I had an academically strong class that year, and their growth was insane,” said Pam Sutton, the instructional coach.

That’s when the thought of learning a new program started to sell pretty easily to the rest of the school.

“We started to see that making this one change in our phonics program could have a really big impact,” Sutton said.

As phonics preparation strengthened in Whiteville Primary, the data suggested shortcomings with phonemic awareness instruction. So the district bought an instructional program for that, too.

“Some of them were like, ‘Oh, no, not another program,’” said Katie McLam, the district’s director of curriculum and instruction. “And we’re like, well, we really want you to try it, because it’s gonna make a difference.”

At the district’s Pre-K through second-grade school, the teachers administer a primary spelling inventory for students. It tests things like initial consonants, final consonants, and short vowels in kindergarten, and moves on from there to things like digraphs and blends.

Teachers began focusing more on phonemic awareness as they went through LETRS training, but outcomes didn’t immediately rise. Student gains on the primary spelling inventory following use of the new program helped teachers buy in.

“They said, ‘Oh, my goodness. They’re really growing,’” McLam said. “But they had to see that it really worked, because if you just talk about something, but don’t actually put it into action, it’s not going to work.”

Knowing the ‘why’ before choosing the ‘what‘

Stanly County Schools began its instructional alignment with the science of reading years before the state law. Before the pandemic, the district noticed gaps in instruction. It noticed that the curriculum was working for some students, but not all. It’s a now-common refrain across the state.

So Plummer convened a team, set up a reading resource fair, and invited vendors to present their materials. Some vendors walked the team through their resources in detail, explaining the research basis and how the curricula would help students. Others put on more of a dog-and-pony show, Plummer said.

He narrowed the list of vendors to a few, and was almost ready to present a recommendation. That’s when the district’s superintendent walked into his office. He had read about Mississippi’s reading gains, and how it came on the heels of a law that grounded instruction in the science of reading. He laid down a stack of documents.

“I mean stack on stack on stack of every article, every educational leadership magazine, anything he could get his hands on about the science of reading,” Plummer said.

The superintendent wasn’t trying to put a halt to adopting new curriculum, he just wanted to make sure all the decision makers clearly understood which direction they wanted to go. So Plummer dove into the research.

“And I think that when the science of reading came along, that’s when we really got to the heart of it — not only are we not giving teachers what they need, we’re also not giving students what they need,” Plummer said. “And we’re jumping ahead too far looking at curriculum first.”

DPI’s efforts to help districts figure things out

The Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021 requires that the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) review and provide feedback to school districts on curriculum and instruction. The law required each district to submit an explanation of curriculum and instruction by this past December, and DPI must review all submissions by this November.

DPI convened a committee of reviewers that includes a mix of staff from the Office of Early Learning and Integrated Academic & Behavior Systems, to ensure alignment between instruction and a multi-tiered system of supports.

The reviewers use a spreadsheet that looks at core instruction through the lens of environment, curriculum, and instruction. Districts submit a description of the time and length, frequency, group size, and other factors related to instruction.

The reviewers take the spreadsheet and draft a one-pager to districts with recommendations, including the top three issues for the district.

“If we gave them all that rigamaroo, they’d never read it,” Bendheim said. “We wanted to give them just enough to get started, and then we have consultants follow up and do one-on-ones with them.”

Here’s a sample:

Your foundational skills curriculum and supplemental have strong alignment to additional components; you’ve recognized a gap. An area to think further might be who to consider is offering instruction.

“Some of them had their teacher doing core, supplemental, and intensive [instruction] — well, that’s not happening,” Bendheim said.

When thinking through plans to intensify, make sure and consider how the group is progressing, the sample document continues.

“Because a lot of them looked at intervention as an individual thing, but you might have a group where the whole group is progressing except for one student,” Bendheim said. “But then you need to look at what you’re doing for that student.

“But you might have a group where no one’s progressing, so there’s something wrong with instruction, the environment, the amount of time, curriculum, whatever.”

While the deadline for feedback isn’t until November 15, the Office of Early Learning has promised districts a response within two weeks because it wants them to have the opportunity to amend instruction this year.

So far, only 10 districts have been approved without any comments. All other districts were approved with comments. The Office of Early Learning decided against not approving any in this first year.

“We wanted them to get funding,” Bendheim said. “If we said ‘not approved,’ they wouldn’t have got funding, and it’s not right for districts who are still learning – some starting cohort three. Because some of them need the funding to adjust and deal with the curriculum – like the [Clinton City] example you gave.”

So what do districts in Clinton City’s situation do for now?

Clinton City Schools is making it work, but it’s not easy. And their situation may hamper – at least for now – some of the progress they think is within reach.

It didn’t take long to realize there were problems.

“(The curriculum) doesn’t follow that scope and sequence, so that means I have to jump from here to here to here to here,” Melenas said. “So there’s a lot of jumping around when we’re talking about phonics and phonemic awareness. And that’s a lot of work.”

But there wasn’t enough money to pay out the sum on the curriculum that was purchased before her arrival, and before the state enacted its reading law, as well as buy a new curriculum.

“Maybe if we lived in just a reading bubble,” Melenas said. “But we don’t.”

The district needs curricula for other core subjects, plus funding for human resources – it currently has no instructional coaches or reading specialists, for instance.

But, using ESSER funds, the district does employ two interventionists. So Melenas turned to them. They sat down and went through the curriculum and figured out a new order for teachers to use it in – as well as finding instructional materials to fill in gaps.

“And their job is not curriculum, their job is not even supporting teachers,” Melenas said. “Their job is literally to intervene with students, but I had to pull them last year and I had conversations with them every single month last year to help us figure out [what to do], because they’re the ones who know reading the best.”

The silver lining for Clinton City is that teachers, administrators, and district leaders are learning a lot through LETRS training. This is happening all across the state, better preparing educators to make curriculum and program decisions.

“And then when we do move over to something different, they at least have a strong knowledge of the science of reading,” Melenas said. “Because they’ve adapted and pulled and they’ve put together things so that when you hand them something that’s better aligned, it’ll be like a breath of fresh air.”

Recommended reading