When Catherine Truitt was a policy advisor for former Gov. Pat McCrory, she recalls, she came across a report whose author argued for using policies that support principals as an efficient way to advance teaching and learning.

“His claim was that principals are a policy lever that’s never pulled,” said Truitt, now the state’s superintendent of public instruction. “It’s always about the teachers – what should the teachers be doing? And his point was, just from an economic standpoint, it’s much more effective and efficient to elevate the principalship.”

In North Carolina, she said by way of example, there are 5,400 administrators and 98,000 teachers.

“So the math is pretty clear,” she said. “But the idea that principals were multipliers of excellence was something that I – never having been a principal – I hadn’t really thought about.”

She’s thinking about it now, though, and she’s leaning on a collection of principals and educators who make up the Department of Public Instruction’s Executive Principal Advisory Committee to figure out what levers to pull.

The committee held its second annual summit Friday in Raleigh and heard about research on the efficacy of instructional leadership from Constance Lindsay of UNC-Chapel Hill’s School of Education, on the role of equity as a lens for principal leadership from Anthony King of the Leadership Academy, and on the function of the principalship from Chelsi Chang from the Aspen Institute.

What is the Executive Principal Advisory Committee?

Truitt’s principal advisor, Tabari Wallace, first convened the committee last summer. Today, it’s composed of 33 principals, former principals, and educators, who provide immediate feedback to Truitt and the General Assembly on policy and legislative issues.

Though it’s only two years old, it has already made an impact on legislation (driving changes to summer camp legislation last summer) and principal pay (by lobbying Truitt to address a feared legislation-induced reduction in principal pay last fall). Now, the committee meets regularly to consider a host of policy issues — including principal pay, principal training, accountability models, and learning loss.

“What we do here, it goes directly to the superintendent, to the State Board of Education, and across the way,” Wallace said, pointing at the state Capitol, “to the legislature.”

What did Truitt say about the principalship?

Truitt believes that improving principal effectiveness is an even more effective lever to pull than teacher effectiveness, she said.

That’s why her approach to school turnaround centers principals. She said her beliefs are informed by her time as a school turnaround coach, and that her preferred approach is to provide principal coaching.

“We need to have principal coaching alongside targeted teacher professional development,” she said. “That is the most realistic and effective way I know to do school turnaround.”

Truitt also said she wants to see both school accountability and principal evaluations redesigned. School accountability is largely measured by school performance grades – the scores that students receive on end-of-grade and end-of-course standardized tests.

This presents a number of problems, she said, including that it measures performance for a school by student performance on a single day. Another issue, she said, is that only a subset of teachers at a school teach subjects that are tested.

“I remember the state board’s eyes popping open when (a principal) explained that he’s got 54 teachers and only six of them teach a tested subject, which means his six teachers at the high school are largely determining the letter grade that that school gets.”

That letter grade is a significant factor in principal pay – which is based on a formula that balances the size of a school and the accountability grade. She wants that to change. While the agency works on a different approach to measure accountability for schools, she’s tasked the principal advisory council with developing a proposal to change principal evaluations.

What’s the committee focused on right now?

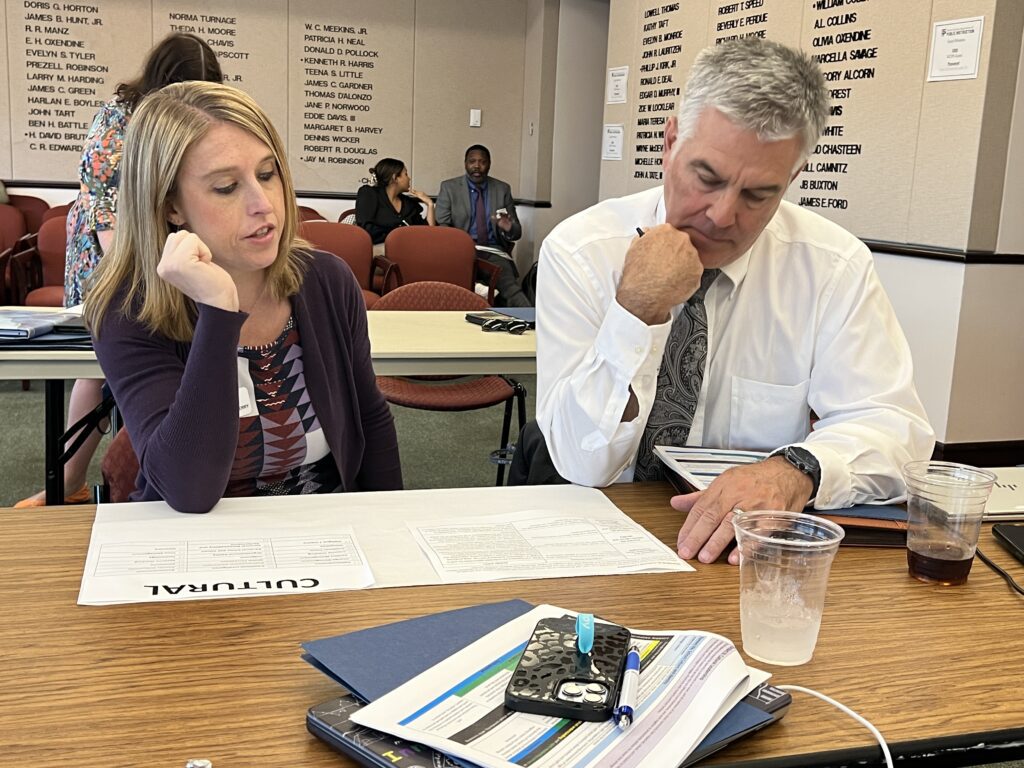

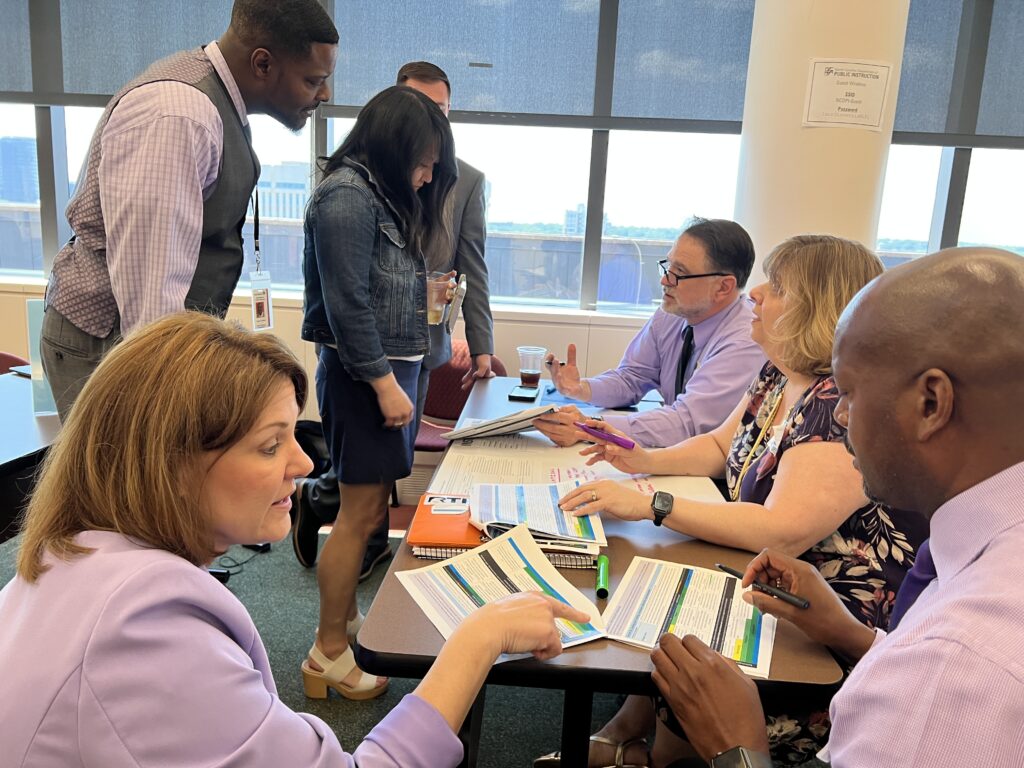

On Friday, the committee focused on learning from outside researchers and consultants, and engaging in group activities to (1) design a profile of an effective principal and (2) discuss redesigning how principals are evaluated (and paid) in the state.

Principal evaluations need to accurately measure school complexity, both Wallace and Principal of the Year Patrick Greene said. Right now, principal pay is based primarily on a school’s average daily membership and its school performance grade.

In addition to redesigning the performance grade model, Truitt agreed that other factors need to be considered to account for the complexity of a principal’s job.

“While I certainly believe that ADM should be one of those factors, we need to have other school complexity factors,” she said. “Things like English Language Learners, poverty level, AIG level – all of those things that really challenge you, professionally, every day should be a part of that calculation.”

On Friday, the committee reflected on the research presented to them and started creating the profile of an effective principal. It focused on what activities and goals principals should invest most of their time advancing.

The group addressed three primary questions: what responsibilities of the principal yield the greatest impact, continue to be the most time-consuming, or could be delegated to other stakeholders?

Connecting these answers to the principal evaluation standards, the committee later broke into groups again to discuss whether the standards appropriately capture the reality and essential aspects of today’s principalship.

At its next meeting, the committee will continue building out the principal profile and continue mapping out measures of school complexity for principal evaluations.