|

|

Perquimans Central Elementary is a school for pre-kindergarten through second grade in North Carolina’s rural northeast. Years ago, when Melissa Fields served as principal there, she adopted Lucy Calkins’s Units of Study, a “balanced literacy” curriculum for teaching reading.

Units of Study is rooted in a whole-language approach to literacy instruction. The version Perquimans used recently received low marks from curriculum evaluators, and many of its practices – such as cueing readers to look at pictures to guess at words – lack evidence that they work for most students.

When Fields was principal, she said, it seemed to work for many young learners. And for those still struggling, Fields tried to offer more intensive support by using grant money to train six teachers in Reading Recovery, an intervention also questioned in recent years.

In kindergartners, first-graders, and second-graders, Fields said, it was hard to see the drawbacks of this approach.

“My ‘aha!’ came when I transitioned to be principal at the high school,” she said. There, she saw her former students – ones who were star readers in early grades – struggling to read.

“They did not have enough skills to sustain that [reading growth],” Fields said. “They were focusing so much on reading for meaning with balanced literacy, that they had not really gotten those decoding skills strong enough. So when the picture cues went away and the text became more complex, we saw that these kids we thought were readers in the primary grades couldn’t sustain that as they got older.”

That’s the “why” behind North Carolina’s strong pivot away from balanced literacy and whole language instruction. After decades of steadily disappointing scores in reading proficiency, the state turned to legislation to bar programs and practices rooted in whole language.

The state enacted the Excellent Public Schools Act of 2021 two years ago this week, but schools are implementing the law, which grounds instruction in the science of reading, for the first time this school year.

Now, all across the state, educators are talking about how the brain learns to read and how to teach in simpatico with that science. Time will tell if it moves the needle – after all, there’s a long implementation journey ahead. But amid national criticism over the use of legislation to guide literacy instruction, many North Carolina education leaders and teachers say things already look and feel different.

As the district’s chief academic officer, Fields now leads the instructional changes in Perquimans — modeling the path away from whole language for teachers.

“The transformation is real,” Perquimans Central Elementary Principal Tracy Gregory said.

Science of reading training is intense, but many are embracing it — and using it

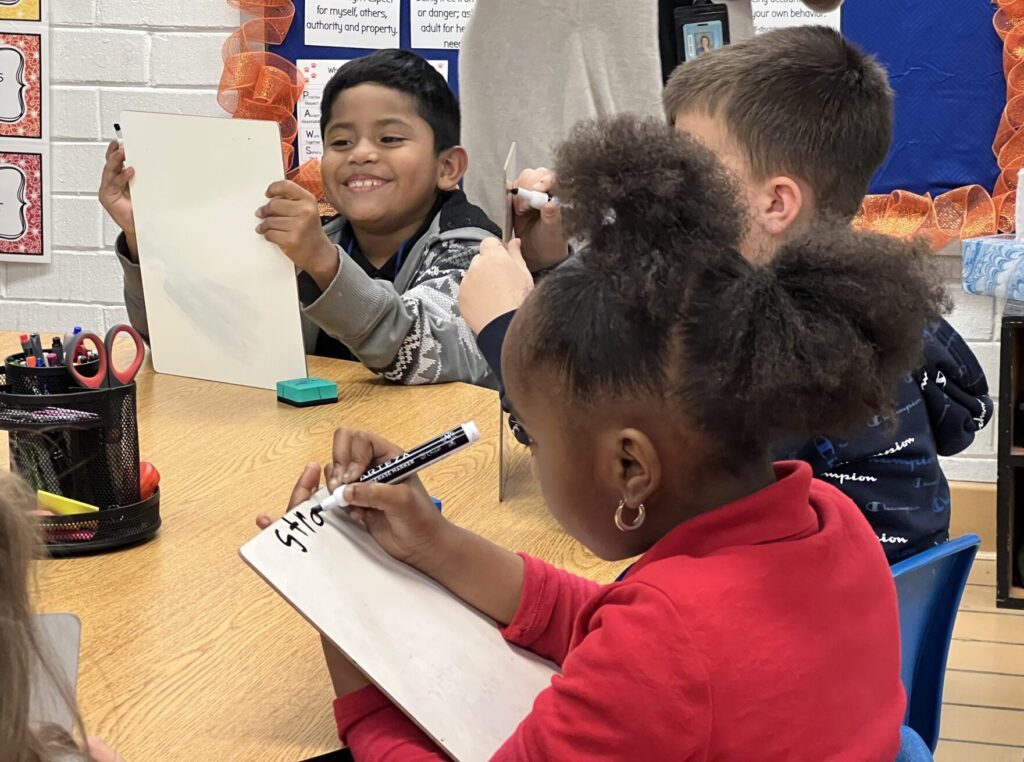

If you pause in the halls of several first- and second-grade classrooms across the state, you’ll notice that instruction looks similar in different districts. Not long ago, it could vary wildly from school to school within a single district. But teachers are now using a common playbook, even if they have different curricula.

As part of the Excellent Public Schools Act, legislators allocated money to train teachers in the “why” and the “how” of the science of reading. The state has spent more than $90 million to train NC Pre-K instructors, elementary teachers, instructional coaches, and administrators in Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling (LETRS).

LETRS isn’t a program or curriculum. It’s training that shows teachers what students need to learn in order to read and write – and it walks through a scope and sequence in which students should learn these things. It covers the primary domains of literacy acquisition – like oral language, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, writing, and spelling. And, yes, it talks about the importance of explicit phonics instruction.

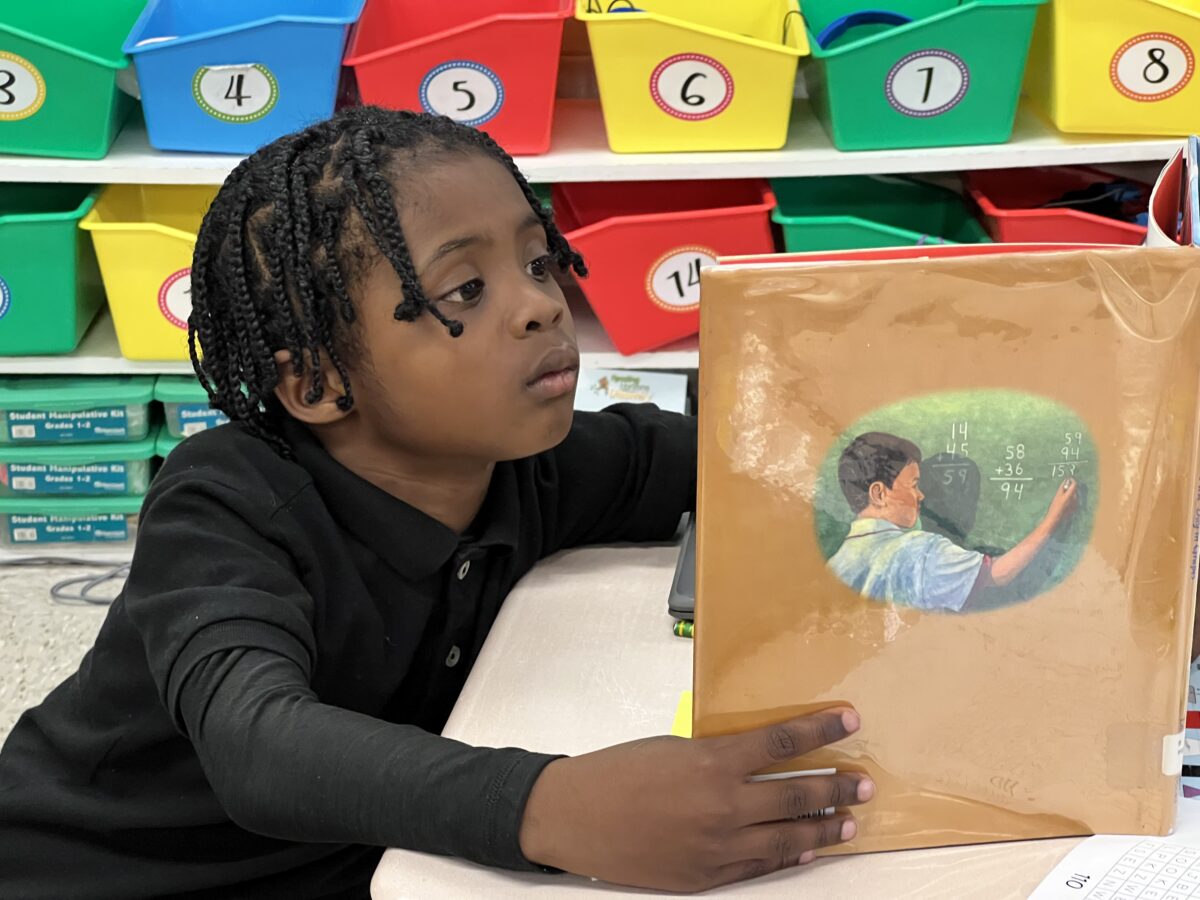

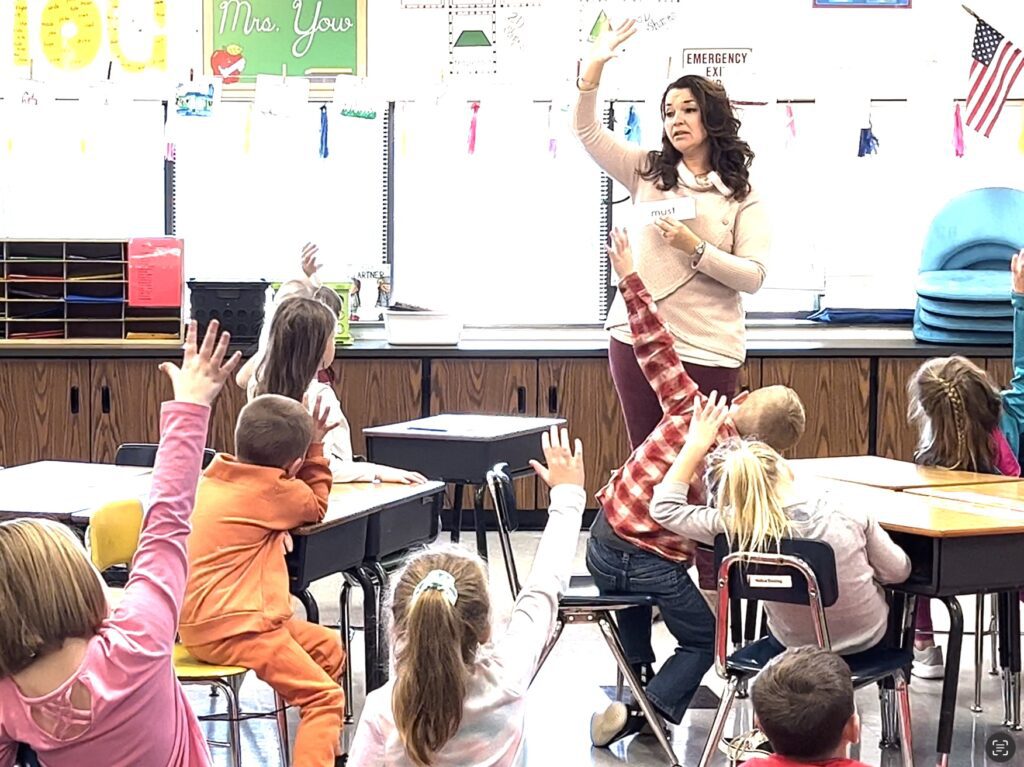

You get a sense when you watch Tricia Yow as she stands in front of her first-grade class at Endy Elementary in Stanly County.

“Let’s talk about our next ending blend,” she says, holding up a card that displays “- st” before pronouncing it carefully. “Remember, those ending blends can be a little bit tricky. When they’re at the end of words, we can hear every single sound in this word, right?”

She wants her students to learn the blend, not focus on the individual letters. She grabs another card with the word “must.”

“We can hear every single sound, but we’ve got to make sure, and we’re going to do that by tapping out the word, OK?”

She puts a hand in the air and stretches out all five fingers. The students follow suit. The class taps a finger for every sound they make – /m/ /u/ /s/ /t/.

“Now, I’m telling you,” she repeats. “These ending blends, they’re very quick, right? So when we’re tapping it out, we have to make sure we listen for the sounds of those blends, OK? We slow it down. We tap it out. OK, eyes up here. Let’s tap it one more time. Ready?”

The students tap out the sounds, tapping separately but quickly for /s/ and /t/.

This example is now typical of instruction in elementary school literacy blocks. To adults who already know this stuff, it may seem like overkill. As teachers now know, it’s actually critical for wiring kids’ brains for reading.

Students are playing with and manipulating sounds. Instruction no longer starts with letters. Teachers don’t expect students to already know that /s/ and /t/ make separate sounds at the end of the word “must.” They teach the blend explicitly, and repeat the instruction until a student masters it.

Yow is engaging the students with hand activities and eye contact, to keep their attention and activate other parts of the brain. Sometimes, teachers will pause to make sure students know the meaning of the word they’re decoding.

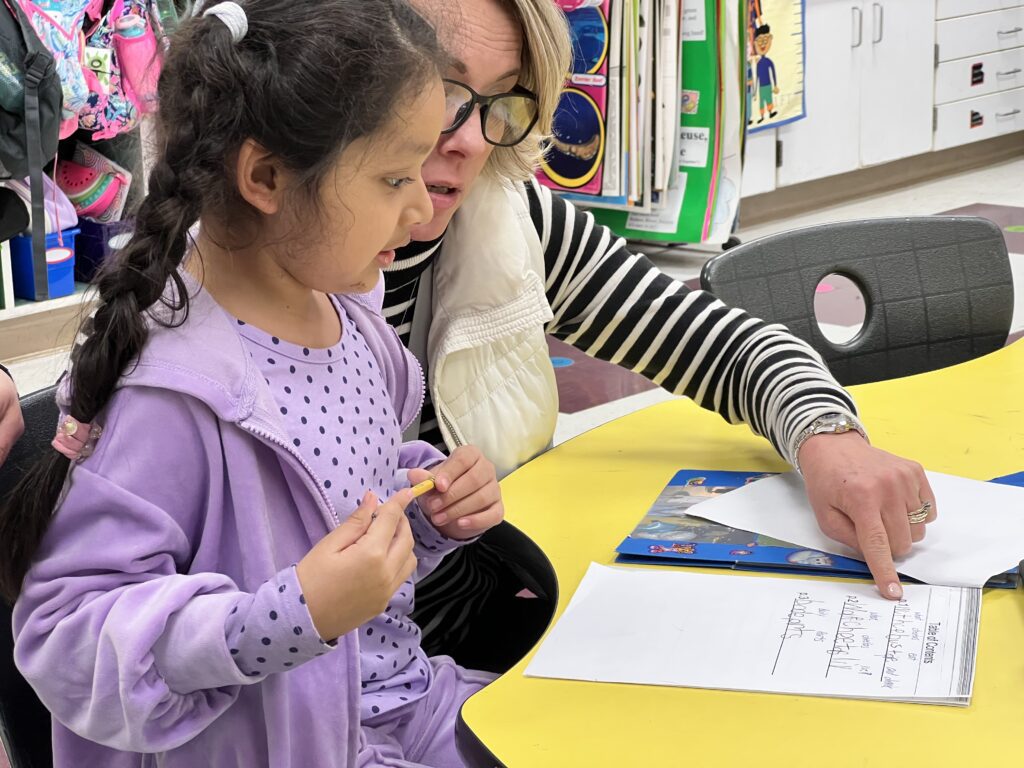

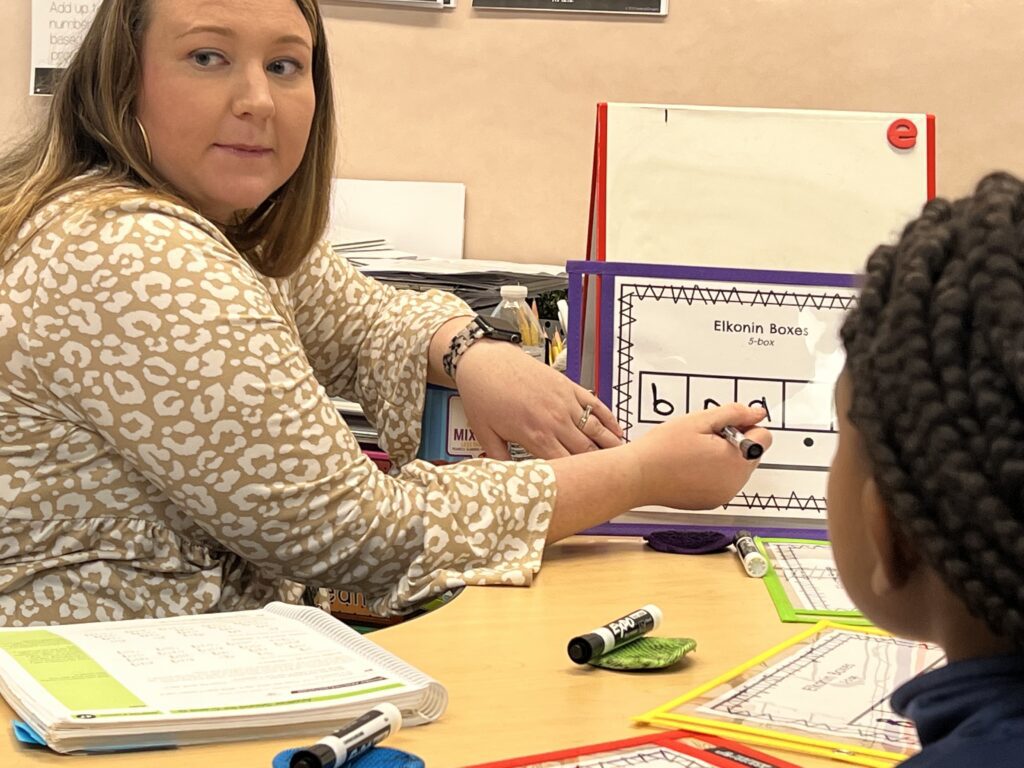

That’s what MaceLynn Clifton is doing with her small group of second-graders at Whiteville Primary.

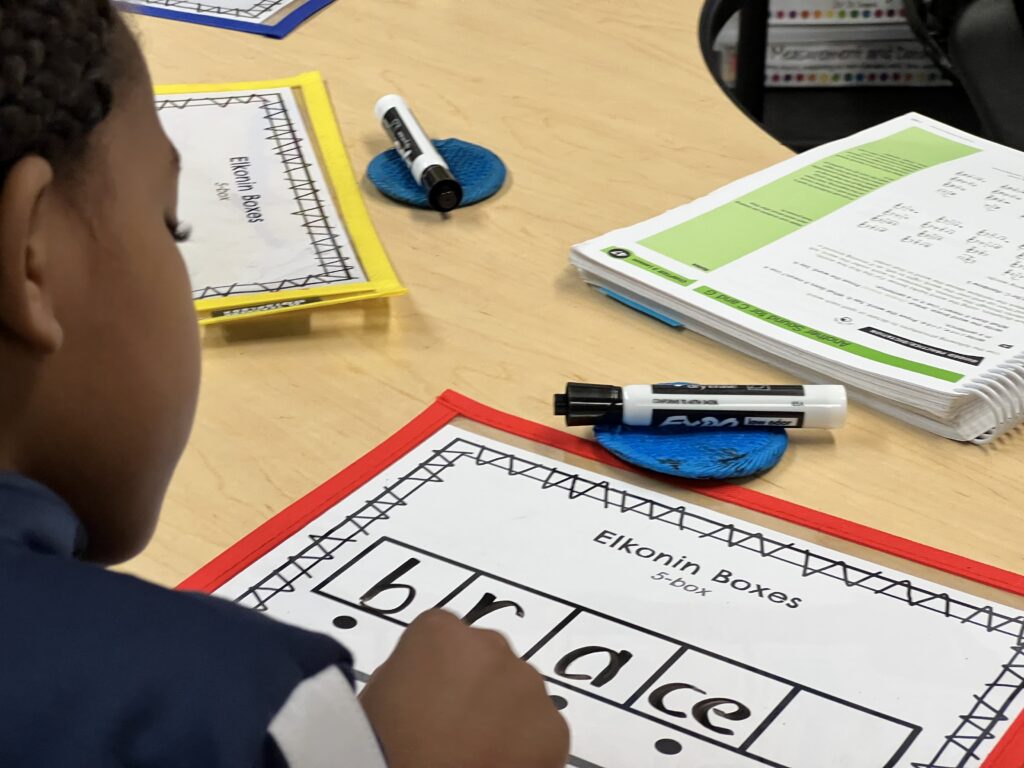

“The word is brace,” she says, and she repeats it one more time. The “ce” at the end makes an /S/ sound, and her Reading Horizons curriculum teaches it alongside the /S/ sound that “ci” can make, calling them both “rainbow s” sounds.

As Yow did with her class, Clifton has her small group tap out the sounds – /b/ /r/ /a/ /s/. Four sounds, she confirms with them. She makes sure every student gets that. She pauses for a moment and continues.

“I might need a brace if I hurt my leg or my arm,” she says. “Kind of like a cast. Or you could use it in another way. Somebody could say, “I had to brace myself on something.’ It means you had to get steady, you had to find something to hold on to.”

Teachers are moving through short vowel sounds and blends. Teachers help students deconstruct syllables, and talk about how vowels sound different in closed syllables versus open syllables.

“I think they’re almost forgetting how they used to teach,” Gregory said. “There was a big pushback at the beginning. They were used to Reading Recovery and whole language and looking at the picture instead of decoding the word. But when we brought in the data, that was a turning point because the teachers want our students to be successful – not just here, but when they move on.”

Making LETRS work, for teachers and students

LETRS training began in 2021 and covers 160 hours of study across eight units. It takes two years to complete. The rollout was bumpy, coming while in-person schooling resumed after COVID-19, but the mood has been more positive this year.

“I think the resistance was not because teachers didn’t appreciate it, or that teachers didn’t believe in what the science of reading is offering for us,” said Lynn Plummer, director of elementary education in Stanly County Schools. “I think the resistance just comes from the time constraint and putting my whole heart into this job and working eight, 10, 12 hours a day, but then I’ve also got to find time outside of my school day to complete this additional training.”

But teachers find it more manageable as districts get better at building LETRS time into their calendars. The state divided districts into three cohorts for the training. The first cohort started in August 2021 and scheduled to finish this summer. The final cohort started at the beginning of this school year and is about halfway through.

“But we’re already starting to hear, anecdotally from teachers, that while the amount of time involved in LETRS is very overwhelming, the content is helping them,” said Melissa Hedt, Asheville City Schools’ deputy superintendent of accountability and instruction. “They’re already finding ways to apply the content. We thought we’d hear that more in year two … but I’ve been surprised to already be hearing teachers and school principals starting to talk about how they’re seeing shifts in classroom practice.”

And districts are sensing an impact from the instructional shift already.

“I think our second-grade teachers would probably tell you that they are seeing students come to them with a much stronger foundation of phonics and phonemic awareness and having those foundational skills under their belt,” said Plummer, whose district began LETRS about two years before the state passed its law.

“It’s really given kindergarten teachers, first-grade teachers – even second-grade — the permission to slow down a little bit and don’t push comprehension from the get-go,” he said.

Whiteville City Schools is similar to Perquimans, with students spending kindergarten through second grade at one school before transitioning to another school for third through fifth grades. Before this year, it was sometimes a rocky transition for rising third-graders.

“Our teachers over there were like, ‘Oh, no. We’re losing something in the transition,’” said Katie McLam, the district’s director of curriculum and instruction.

It was a troubling trend that grew more disturbing during the pandemic. But as teachers dove into both LETRS training and reading assessment data, the root cause for the trends became apparent.

“Memorizing words might get you through second grade,” said Pam Sutton, the instructional coach at Whiteville Primary. “But beyond that, you need skills to attack your science words, your tier three words, those social studies words – to be fluent. And that looks like memorization, but we get to that fluency in different ways.”

Early returns show promise for reading outcomes

At the beginning of last year, 22% of kindergartners in Perquimans were assessed as proficient. At the end of the year, it was 64%. That 42-point gain was higher than the state and national averages.

“And we saw similar gains like that in first grade and second grade, where we were really kind of outpacing the growth of the state and the nation,” Fields said.

Whiteville City and Stanly have seen similar growth, McLam and Plummer each said. This month, DPI presented statewide data showing gains measured using Amplify’s mCLASS with DIBELS 8 assessment.

The gains are motivating teachers as they navigate the gargantuan task of completing LETRS on top of everything else. It’s a marked shift from early reports during the first cohort’s commencement of LETRS. The rollout happened quickly, with the first cohort beginning just four months after the state enacted its law.

Many districts didn’t have time to prepare, so their calendars didn’t block off adequate time for LETRS training. Teachers reported feeling overwhelmed, and because the early units of LETRS focus more on the “why” of the science rather than the “how” of instruction, some teachers said they didn’t think the training was worth the stress.

“But I think that as they’re seeing success, and they start seeing that students are doing well – especially at the foundational level – we’re seeing increased success,” said Theresa Melenas, executive director of instructional services in Clinton City Schools. “That will only spur teachers forward.”

Districts advise patience in transition to science for reading

There’s still work to do.

Leveled readers, books designed to help students predict words, still find their way into students’ hands in some schools. Teachers, used to teaching letter sounds first, sometimes slip into old habits. Some research says background knowledge is important to developing as a skilled reader. LETRS handles strategies for incorporating that in later units, so many schools haven’t seen significant instructional shifts there.

But it’s year one of the journey with the science of reading. Several district leaders said they’re watching for three to five years down the road before the state sees significant movement in reading scores across the board. Some said they expect to see major gains when the kindergartners who come in after full implementation matriculate to third grade. That would mean the 2027-28 school year.

“People can’t expect this to be a quick fix,” McLam said. “It’s not going to be, and they want it to be. I understand that. I mean, we all want our children to be successful in life. But this is just gonna take some time, and I think we just have to keep proving this through sharing the data and the information that we get.”

And by watching and listening to the teachers. That’s what lifts the spirits of Rebecca Little, an instructional coach at East Albemarle Elementary in Stanly County.

“I’m blessed with the teachers we’ve got in this building,” she said. “They’re willing to say, ‘What’s best for this kid?’ Even though they’re tired, it’s, ‘What’s best for this kid?’”