|

|

A pilot program proposed in the state House’s budget would help families afford child care if they work at participating businesses in three counties.

An amendment to the budget proposal would allocate $900,000 for each of the next three years to the program, which would recruit businesses interested in helping with the cost of their employees’ child care.

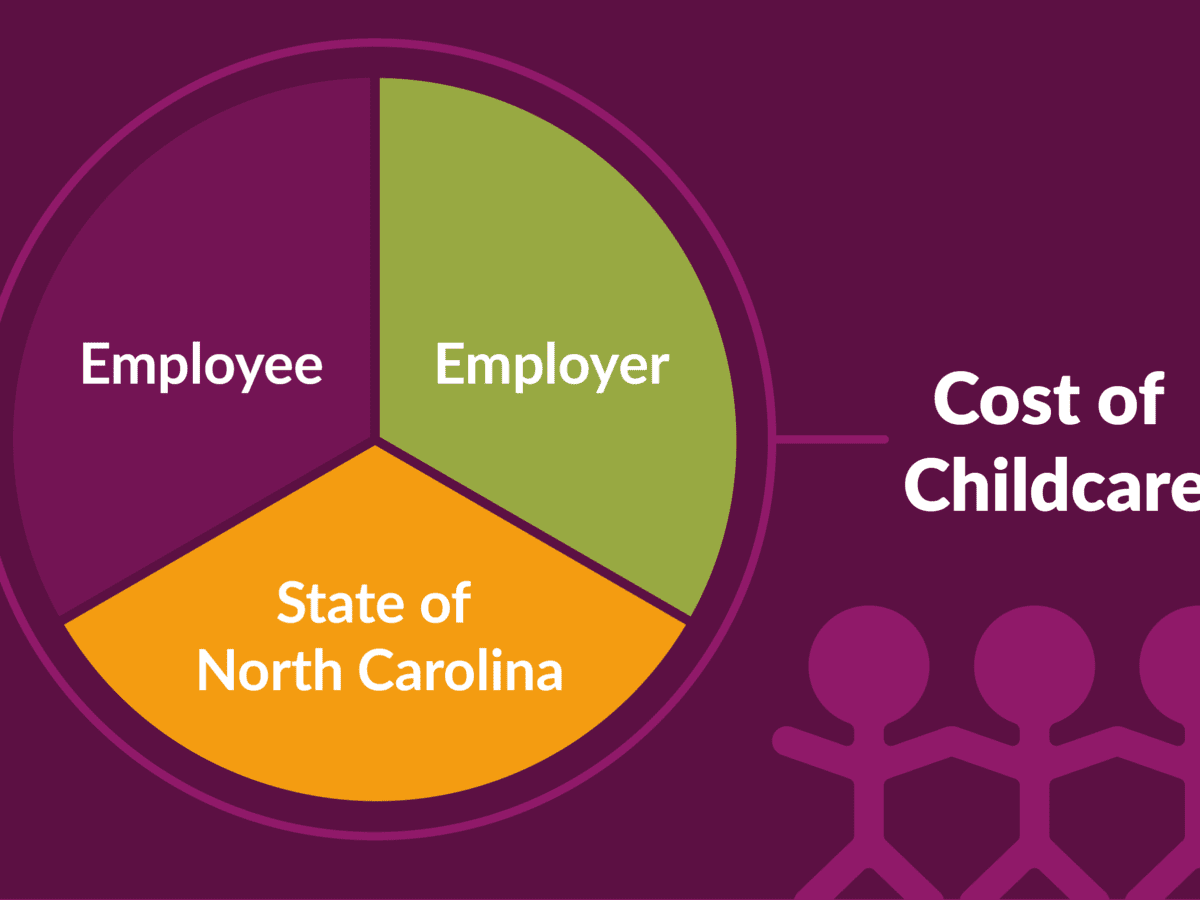

Eligible employees would pay a third of the cost of child care at licensed programs. Their employers would foot another third, and the state would pick up a third. After the pilot is over, the state would report to the legislature on what it would cost to expand the program statewide.

An amendment from Rep. David Willis, R-Union, added the pilot to the House budget plan last week. The program is aimed at helping families who make too much money to qualify for subsidized child care but still struggle to afford care.

“We’ve got a number of folks who aren’t going back to work right now just because it doesn’t make financial sense for them to do so,” Willis, who also owns and operates a child care program, said in an interview with EdNC. “Hopefully, this allows them to have an opportunity not to have to choose between child care and work. They can have both.”

Employees would have to work at a participating business, have a household income between 185% and 300% of the federal poverty level, and not otherwise be eligible for subsidized child care.

The House is expected to approve its budget proposal this week. The Senate will release its plan next, and then the two chambers will negotiate what makes it into the final budget.

The pilot project was one of five priority items filed by the chairs of the legislature’s bipartisan early childhood caucus — Willis, Rep. Ashton Clemmons, D-Guilford, Sen. Jim Burgin, R-Harnett, Lee, and Sen. Jay Chaudhuri, D-Wake.

How would it work?

The Division of Child Development and Early Education and the North Carolina Partnership for Children would choose the pilot’s three counties. The bill requires the counties to be geographically diverse and one of them to be labeled Tier 1 by the Department of Commerce, the most economically disadvantaged ranking.

Local Smart Start partnerships (there are 75 across the state) would be responsible for recruiting the businesses, determining eligibility of participants, splitting the cost evenly among the three entities, and facilitating payments.

The pilot is a small piece in a larger puzzle of how to fund child care, Willis said. The current model is operating with high costs and insufficient spots for parents, low wages for staff, and negative consequences for businesses.

“The current child care model that we have in the state long-term is unsustainable, as it is today,” Willis said. “We know we’ve got to find a better way forward — and this provides us with an opportunity to try something different.”

He has heard from businesses who are interested in helping, he said.

“For the first time since I’ve been involved in child care, we have the business community proactively coming to us and saying, ‘Hey, we want to be involved. We want to help.’ We don’t always have big employers that can can do that, so with the tri-share model, we have the opportunity for much smaller employers to be able to participate and to provide a valuable benefit to their employees.”

Looking to Michigan

The program is based on “MI Tri-Share” in Michigan — which similarly started as a pilot in 2021. The model now receives recurring funding from its state legislature and operates in 59 of the state’s 83 counties. It serves 253 families and 349 children, with 138 participating employers and 227 child care providers, said Cheryl Bergman, CEO of Michigan’s Women’s Commission. The commission oversees the program, which the state legislature expanded in 2022 and 2023.

Each $300,000 grant goes to 13 regional “facilitator hubs,” which are all nonprofits or school districts. Four of those regions, Bergman said, are covered through philanthropic funds.

“Is it a child care subsidy program, or is it a workforce development program?” Bergman said people have often asked of the program. “Well, it’s both.”

The idea was originally part of an initiative in Grand Rapids, including its local chamber of commerce, aimed at attracting businesses and increasing employer retention, Bergman said.

“It’s truly changing families’ lives, and the employers who are participating, they’re seeing some attraction for sure by offering that benefit once they get the word out, but mainly what we’re hearing from employers right now is the increase in retention,” she said.

“You’re getting two thirds of your child care paid. I’d be pretty loyal to that employer as well.”

‘Tri-share really does not address the capacity issue’

The main challenges in implementing the program, Bergman said, are lengthy timelines for getting businesses on board, low capacities of the facilitating organizations, and the lack of child care availability in certain communities.

There has been tons of interest in businesses, she said, but logistical delays mean the process of “getting them actually signed on the dotted line” can take three to six months.

The facilitator hubs are able to use 12% of the $300,000 grant, or $36,000, for administering the program. The North Carolina pilot caps the administrative usage at 9%.

Bergman said administering the program is “a heavy lift.” She said the hub that has been the most successful has been able to use other funds to dedicate a full-time position to the program.

“Everybody else is piecing it together,” she said.

Even with help covering the cost, some parents can’t find care, Bergman said.

“In some of our areas, especially the rural areas, we have deserts,” she said. “We don’t have enough child care. So we may have employers and employees who are ready to roll but can’t find a spot anywhere.”

The Michigan program pays providers at market rate, Bergman said. The model does not address the availability of child care programs or the low wages of teachers. “Tri-share really does not address the child care capacity issue,” Bergman said.

North Carolina faces similar availability issues. There’s capacity for about 18% of all infants and toddlers, and 27% of infants and toddlers with working parents, according to a 2022 report from the Child Care Services Association.

“Anything that we could do to help bolster the tuition rates and the amount that we’re able to pay those providers, I think it’s going to help attract new providers,” Willis said.

“Obviously, it’s not going to be the silver bullet that solves everything, but I think adding one more very valuable tool to the mix is critical.”