On Thursday at the State Board of Education meeting, state Superintendent Catherine Truitt presented a new structure that she hopes will help the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI) better assist low-performing schools.

Before she started, she emphasized that while schools may have been designated low performing, that doesn’t necessarily mean they are.

The school performance grades determine which schools are low performing, and there has been a lot of pushback over the years on how those grades are calculated. They are made up of two numbers: academic performance, which counts for 80% of a school performance grade, and academic growth, which counts for 20%. Performance equates to how well students do on one day taking a test, whereas growth essentially measures how much they’ve learned in a year.

DPI is hard at work trying to come up with an alternative school accountability proposal to present to the General Assembly. And nearly everyone involved agrees that growth should count for more. But for the moment, the state is stuck with the low-performing designation as determined by the current model.

What’s important, Truitt said, is to understand why a school got that designation.

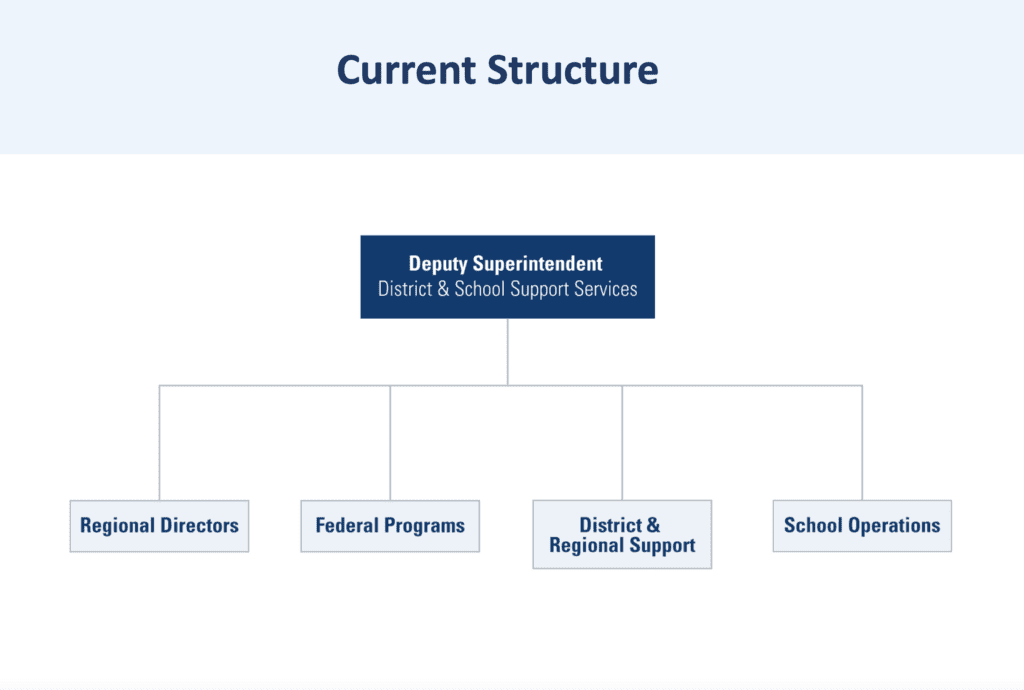

Before presenting her new model for assisting low-performing schools, Truitt took the Board through the current model, which essentially has one deputy superintendent overseeing all the various departments that deal in some way with low-performing schools.

She pointed out to the Board that multiple groups are essentially dealing with low-performing schools separately. Staff that act within the current model meant to help low-performing schools are one group, while those who work under federal programs are another. In addition, low-performing schools might also be getting visits from people in other departments, such as the Office of Early Learning to talk about literacy plans. She said it amounted to a “scattershot approach.”

“None of those supports are coordinated,” she said. “This is problematic because when these supports are not coordinated, it becomes a barrier to improvement.”

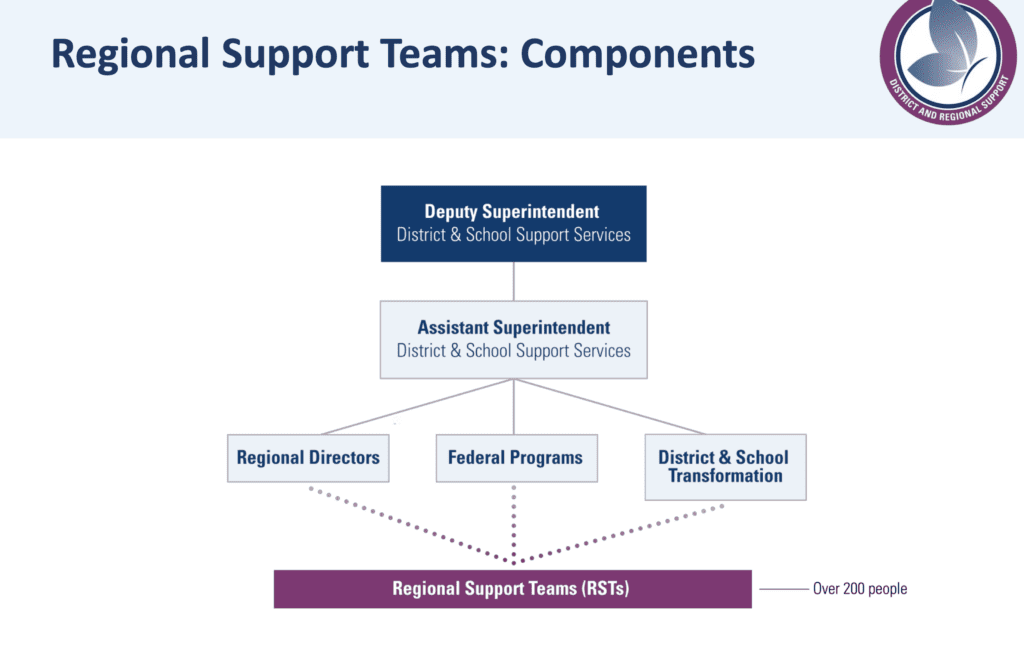

Under her new model, DPI will use all staffers who work in the field with schools in a coordinated way to make sure there is one unified approach to reforming low-performing schools.

Truitt is creating a new position: assistant superintendent of district and regional support (the assistant superintendent title in the slide above is incorrectly named). That person will work under the deputy superintendent and above the three departments in the slide above. And those three departments will oversee the “Regional Support Teams,” 200 people who are already in the field doing work with schools in various areas. By using those 200 people and overseeing them in a coordinated way, the hope is that the new structure will make sure everybody is working toward the same goal: helping these schools get out of low-performing status.

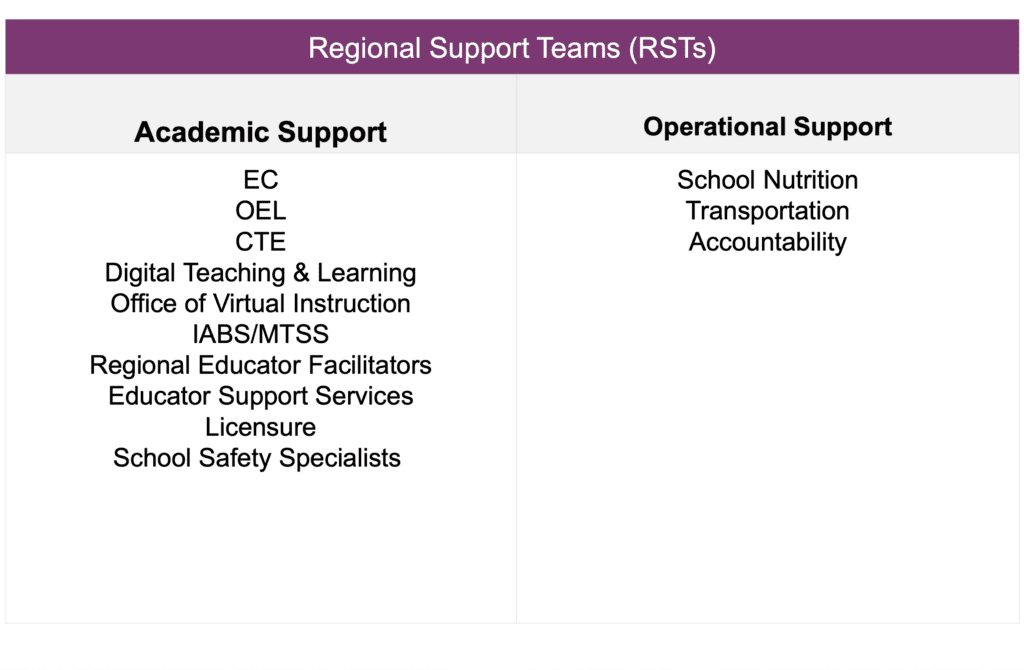

Those 200 people come from the following areas:

Truitt laid out her theory of change in her presentation as: “We will improve outcomes for all students through a coordinated system of field supports that are centrally located at NCDPI but deployed through regional teams nimble enough to meet the needs of individual schools.”

At the conclusion of the presentation, State Board Chair Eric Davis signaled his appreciation for Truitt’s plan.

“I know we’re aligned in how important this is for our students, and I’m grateful to you for bringing this to us,” he said.

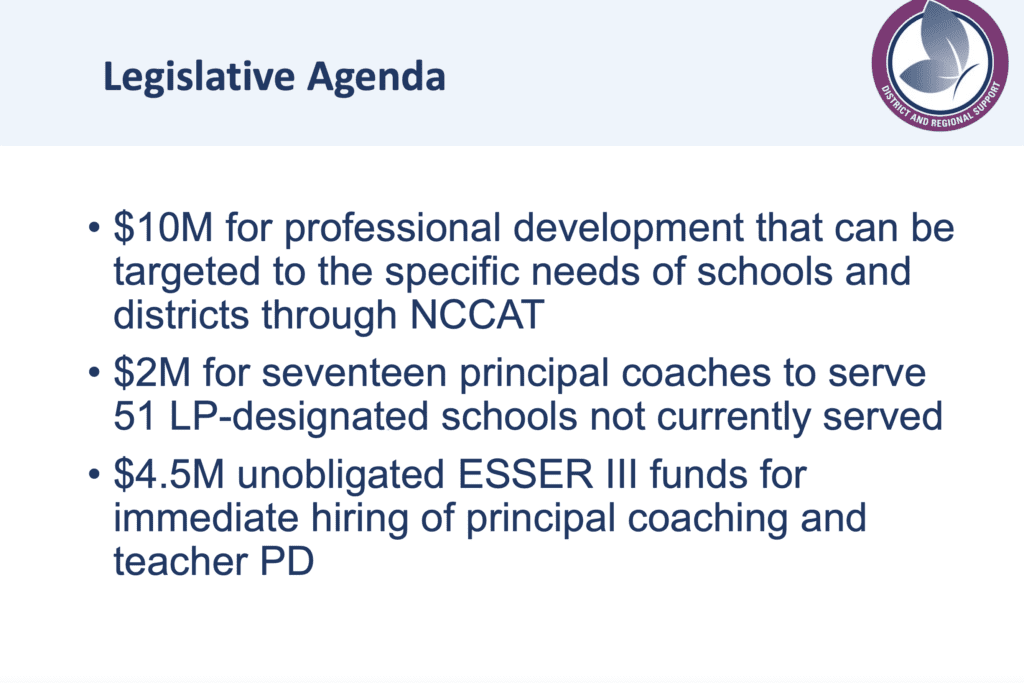

Going forward, Truitt said DPI will need funding and action from lawmakers as well. You can see the legislative priorities associated with her new model below. Below that, you can see her presentation.

Recommended reading