|

|

Millions of philanthropic dollars will be infused into the early childhood system across western North Carolina in the coming years.

The money will aim to strengthen the early childhood workforce, which many are concerned will further shrink when federal relief funds, now being used to temporarily increase wages, dry up next year.

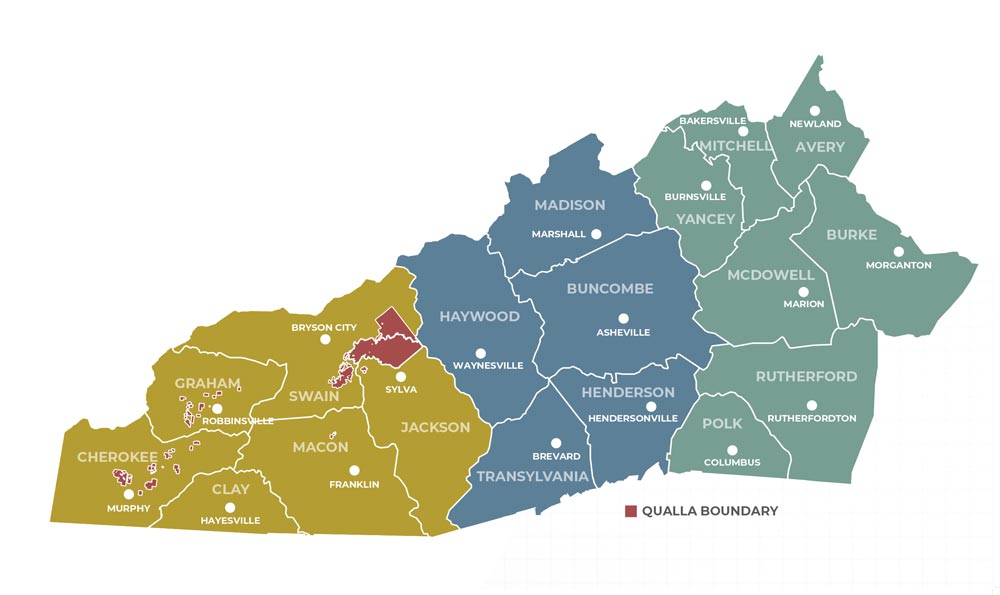

Dogwood Health Trust, a private foundation that serves 18 counties and the Qualla Boundary, last week opened a request for proposals from organizations with ideas on how to improve working conditions, attract new people to the field, and increase access to workforce education.

Nonprofits, education institutions, government agencies, and others who serve the region can apply before midnight on Sept. 16.

The foundation is planning to spend about $5 million in multiyear grants to a handful of organizations, Ereka Williams, vice president of impact for education at the foundation, said during a webinar last week. The exact amount of total funding and the number of recipients has not yet been determined.

In education, “the teacher is the variable that makes the difference, no matter what part of the system we’re talking about,” Williams, who has worked most recently in higher education, said in an interview with EdNC. So it feels right, she said, to focus “on the people that are in front of the room or beside the crib.”

Grantees will receive multiyear grants of $250,000 to $1 million each, according the webinar. The amount will depend on the scope and strength of the initiative and the grantee’s capacity. The foundation is looking for proposals that approach challenges through an equitable lens — when it comes to the types of providers included, the demographics of those who get supports, and the outcomes and curricula used.

“It’s needed because the cliff (when federal stabilization funding ends) is coming at us quicker and it’s steeper than we thought it was gonna be,” Williams said. “[We’re] hoping to extend some of those innovative things that our colleagues were able to try and do, through the stabilization grants, through some of those monies … I’m hoping that we’ll continue that momentum for our partners in the region.”

According to the foundation, priority will be placed on proposals that address at least one of the following:

- Approach, curriculum, training, and evaluation.

- Career ladder attainment (growth of existing workforce and/or growth of new recruits).

- Leadership opportunities for members of the workforce who are BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color), from rural communities, are first-generation credential holders, and/or have faced a lack of access to resources and opportunities.

Local focus, statewide problems

Williams said the foundation is focused on the first 2,000 days of children’s lives across four realms: housing, economic opportunity, health, and education.

Its early childhood focus is informed by listening sessions and research from the Child Care Services Association, which released an analysis of the region’s early care and education landscape last month.

The association’s findings highlight problems the rest of the state and country face in supporting young children’s development.

Twenty-two percent of children younger than 6 in the area were living in poverty earlier this year, the report found — an improvement since January 2020, when 33% were living in a family with an income below the federal poverty level. The report said this improvement probably was due to increased pandemic-related support for families, such as the Child Tax Credit, which has since been eliminated.

There is an unmet need for child care, the report found. Fifty-nine percent of the nearly 50,000 children under 6 years old in the region were living with a single working parent or with two working parents in February. Yet only about 23% of children under 6 were in licensed child care programs.

Enrollment declined by about 15% from the start of the pandemic to February, and the number of licensed programs had slightly decreased, from 463 programs in February 2020 to 447. Thirteen of the programs that have closed in the last two years were centers, and three were family child care homes.

Child care is unaffordable for most, with the cost representing about half of the income of a single parent who lives at the poverty threshold, the report found, at $800 per month for children younger than 3 and $700 per month for children ages 3-5.

There is a particular need for infant and toddler care, with less than half of licensed programs serving children younger than 3.

Instead of building more spaces for children, Williams said, staffing was the factor she kept returning to when thinking about meeting the needs of families.

“I want a brand new center for people’s babies to be in, but we’ve got to have staff,” she said. “And I kind of feel like we’ve skipped the biggest elephant in the room, so I want us to focus on workforce and what we can do to support the workforce heading into these beautiful buildings that we want to revitalize.”

In 2019, directors were earning an average of $20 to $22 per hour, teaching staff were earning $11 to $12 per hour, and family child care providers were earning $8 per hour, the report found. Dogwood plans to study the workforce more in the future.

Williams said the family child care providers, who make the least and who have been closing their operations in the last decade across the state and country, were a particular part of the ecosystem in need of resources. Family child care is often more affordable and more accessible for parents working nontraditional hours — with an older workforce than in center-based programs.

“They lift up child care for families in ways that centers can’t or do not in some spaces and in some communities,” Williams said.

She pointed to a drop in family providers in the western part of the foundation’s service area in recent years. “What happened to those families’ needs and that care? … I wonder about what happens when we lose that kind of volume in this ecosystem.”

Pulling other levers in the future

The foundation hopes to learn lessons that can be shared across the state, Williams said.

“Grant-making is one slice of the whole pie of what we could do in this space,” she said. “There’s advocacy and influence and other types of capital.”

“We know that that investment on the front end pays exponentially on the back end,” she said. “… It is worth our time at Dogwood to begin on the front end and invest well and wisely. So we will put the resources — grant-making dollars for now, other resources later when those lessons show up to us in a concrete way — we’re so looking forward to that. The community has spoken. They’ve prioritized this, and we’ve listened.”

Editor’s note: Dogwood Health Trust supports the work of EducationNC.